Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

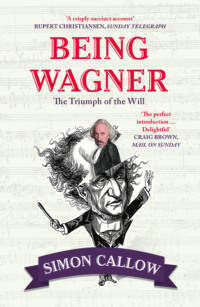

Kitabı oku: «Being Wagner: The Triumph of the Will»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © 2017 Simon Callow

Cover photograph of Simon Callow © Richard Pohle

Simon Callow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers will mbe glad to rectify any omissions in future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780008105716

Ebook edition: January 2017 ISBN: 9780008105709

Version: 2017-12-07

DEDICATION

To David Hare,

friend, adviser, beacon.

EPIGRAPH

‘Only those friends, however, who feel an interest in the Man within the Artist, are capable of understanding him.’

Richard Wagner,

A Communication to My Friends, 1851

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Vorspiel

1 Young Richard

2 Out in the World

3 Doldrums

4 Triumph

5 The World in Flames

6 Pause for Thought

7 It Begins

8 Suspension

9 Limbo

10 Enter a Swan

11 Towards the Green Hill

12 The Long Day’s Task is Done

Coda

Chronology

Wagner’s Works

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

FOREWORD

In the summer of 2012, Kasper Holten, then artistic director of the Royal Opera House in London, asked me to create a show to celebrate the Wagner bicentenary. I threw myself at the vast literature, and emerged astounded at what I had found. I knew his work very well – had been a Wagnerian since early adolescence, knew all about leitmotive and the Tristan chord – but, apart from his notorious anti-Semitism, knew remarkably little about the man, his vast intellectual scope, his rascally sex life, his revolutionary politics, his heroic struggle to create Bayreuth. In particular, I knew nothing about his quite extraordinary personality. I determined to put what I had discovered into the one-man show I was evolving, with the result that the text that I read out on the first day of rehearsals lasted four hours. People came and went, had lunch, returned, and came back to find me still droning on. I couldn’t bear to leave anything out. The moment we started rehearsing, of course, pretty well the whole of that text was jettisoned. With light, images, props and above all with music to evoke the man and his world, I pared it down and down. The first preview still lasted two and a half hours; I cut an hour from it overnight. The show we finally evolved – Inside Wagner’s Head, I called it – gave, I think, a pretty fair impression of the furor he generated, both in himself and in other people.

The play tried to answer the question of what it was about him that creates such violent emotions, even today, two hundred years after his birth. When I was working on it, I bumped into a friend, an eminent, an internationally famous, musician, and told him what I was doing. ‘Why??’ he protested. ‘Dreadful music. Dreadful man.’ This book asks the same question, but in a different way and from another perspective. It offers a sustained though not, of course, comprehensive examination of how this diminutive and often rebarbative man, with only the sketchiest of formal musical training, imposed his work and his view of life on the world. In unflagging pursuit of his goal, he was titanic, demiurgic, super-human – and also frankly, more than a little alarming. No one was ever neutral about him. His personality was so extreme, so unfettered, that he struck many people as teetering on the edge of sanity, both in the way he behaved and in the intemperate demands he made of them. He had, said Liszt: ‘A great and overwhelming nature, a sort of Vesuvius, which, when it is in eruption, scatters sheaves of fire and at the same time bunches of roses and elder’. Volcanic imagery abounds in recollections of him: ‘the little man with the enormous head, long body and short legs,’ wrote the painter Friedrich Pecht, ‘resembled a volcano spewing out fire and sweeping all before him … his true element was the most violent excitement’. Half-admiringly, Liszt described Wagner’s ability to work his way round a room, systematically alienating everyone in it. ‘It is his habit to look down on people from the heights, even on those who are eager to show themselves submissive to him. He decidedly has the style and the ways of a ruler, and he has no consideration for anyone, or at least only the most obvious.’

Many people ran a mile from him. But quite as many were hypnotised by him, eager to catch the bunches of roses and elder that accompanied the lava. However, they approached him closely at their peril. He sometimes had an annihilating effect on those who were drawn to him. ‘I am,’ he remarked to Cosima, ‘energy personified.’ He invited the composer Peter Cornelius, part of his circle of young admirers, to stay with him and write music, but he laid out his terms in advance: ‘Either you accept my invitation and settle yourself immediately for your whole life in the same house with me,’ wrote Wagner, ‘or you disdain me, and expressly abjure all desire to unite yourself with me. In the latter case, I abjure you also, root and branch and never admit you again in any way into my life.’ Cornelius refused Wagner’s generous offer. ‘I should not write a note,’ he told a friend. ‘I should be no more than a piece of spiritual furniture to him.’ It sometimes seems as if Wagner were exaggerating his own ogreishness for comic effect, but if so, the joke was rarely perceived as such, and it often turned nasty. He was quite capable of being amusing, jovial, even, when he was in the mood. He was surprisingly capable of sending himself up. But even on such occasions, he could turn in an instant, suddenly spreading terror where mirth had been before.

This temperamental excess was not a case, as in Peter Shaffer’s presentation of Mozart, of a contradiction between the man and the artist: in Wagner they were one, as he insisted again and again. His temperament and the circumstances of his upbringing gave him access to parts of his psyche that most people – most nice people – put away from themselves. When he wrote music, it was his subconscious, with which he was on such familiar terms, that he sought to express. He went straight to the archetype, and he went in deep. Though his music contains ideas, it deals not just with the ineffable, but with the unspeakable. It unearths what has been buried within us. And some people found it intolerable, right from the moment his true voice as a composer was heard. Critics felt assailed by it, to an uncommon degree. A famous cartoon published in Paris in 1861 when Tannhäuser was first performed there shows a demonic, bug-eyed Wagner climbing inside a huge ear, armed with a hammer and driving a nail through the eardrum, as blood spurts out in all directions. His music was, many critics thought, right from the beginning, in some way unhealthy. Eduard Hanslick dismissed the music of the composer’s highly original spiritual odyssey Lohengrin as ‘mawkish, spineless and often affected: it is like the white magnesium light into which it is not possible to gaze for long without hurting one’s eyes’.

Some people took it even worse: in a letter to his friend Edvard Grieg, the Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson wrote of Tristan and Isolde that it was ‘the most enormous depravity I have ever seen or heard, but in its own crazy way it is so overwhelming that one is deadened by it, as by a drug’. He found the plot to be immoral, he continued, ‘but even worse is this seasick music that destroys all sense of structure in its quest for tonal colour. In the end one just becomes a gob of slime on an ocean shore, something ejaculated by that masturbating pig in an opiate frenzy.’ When Wagner published the libretto of his gargantuan epic The Ring of the Nibelung, before he had written a note of the score, it provoked the pioneer psychiatrist Theodor Puschmann to publish a pamphlet called Richard Wagner: A Psychiatric Study, which roundly described its subject as a monomaniac and a psychopath. Nietzsche, too, after succumbing for a while to extreme Wagnolatry, turned violently away from him, proclaiming that Wagner was not a composer at all, comparing him unfavourably to Bizet. Recently, the British composer Thomas Adès described Wagner’s music as a fungus. ‘It’s a sort of unnatural growth. It’s parasitic in a sense – on its models, on its material. His material doesn’t grow symphonically – it doesn’t grow through a musical logic – it grows parasitically. It has a laboratory atmosphere.’ By contrast, Baudelaire said, after hearing the overture to Tannhäuser for the first time, that the music expressed ‘all that lies most deeply hidden in the heart of man’.

This was something quite new. Or maybe something very old. Something like Dionysiac possession, perhaps. From the beginning, Wagner got under people’s skin. He didn’t care whether his music gave formal satisfaction, or whether it struck people as being beautiful or exciting or dramatic. He was trying to bypass the audience’s analytical brain. His aim was the unconscious, the emotional underbelly, the murky depths of human experience. Feelings were what interested him, he said, not understanding. So it’s hardly surprising that Wagner’s music bothers people. It was meant to. It’s what he set out to do. He wanted to overwhelm his audiences – literally, to knock them off centre. He was a man without boundaries, and he wanted his audience’s boundaries to overflow too.

No wonder that the theatre was where he found himself. The theatre was, indeed, at his very core. He came from a theatrical background: his stepfather was an actor, as were several of his brothers and sisters. He wrote plays from an early age, he staged shows in his model theatre, he gave highly charged recitations. All his life, he acted, joyously giving himself over to amateur theatricals and giving electrifying performances of his own librettos. As with Charles Dickens, it was said of him by shrewd judges that had he chosen to make a living in the theatre, he would have been the greatest actor of his time. There are similarities between the two men. Like Wagner, Dickens created epics from his imagination by sheer willpower, epics teeming with archetypal figures; both men were given to great treks up mountains and down valleys; both of them had an uncanny relationship to animals. These parallels only go so far; the contrasts between them are sharp, but in their way, equally illuminating – Dickens with his essentially comic vision, Wagner with his tragic view of life; Dickens’s art at heart carnival, Wagner’s profoundly hieratic; Dickens deeply in touch with his inner child, Wagner directly connected to his inner infant.

The book I have tried to write aims to give a sense of what it was like to be near that demanding, tempestuous, haughty, playful, prodigiously productive figure, but also to place him in his world. Wagner belongs as much to the history of ideas and indeed to the history of the nineteenth century as he does to the history of music. I am not a musician, either as performer or as musicologist. I am a well-informed music lover, but it would be entirely inappropriate for me to attempt musical analysis. All I can write about is the effect of the music. I am slightly comforted by the fact that this is the only way Wagner ever wrote about music. You will search his copious writings in vain for an analysis of his highly idiosyncratic and complex compositional practice. This originality of procedure is a vital part of what makes him extraordinary, and I have noted the evolution of his musical means. But what has fascinated me above all has been how Wagner served his talent, his exceptional loyalty to it, however rackety a life he might have been leading, however much pressure there might have been to betray it, however hopeless his situation might have seemed. Wagner is in some senses an unlikely hero, but his custodianship of his gifts, despite the reverses of fortune and the vagaries of his temperament, counts as heroic and inspiring, while his personality in all its extremity belongs to one of the most fascinating of all the occupants of the human zoo.

***

Wagner has been written about at greater length than any other composer. Superb books, some short and some hernia-inducingly long, have covered him from every possible angle; primarily interested as I am in how he lived his life day-to-day, my main source has been his own words, in his copious published writings and especially, perhaps, in the letters, great tracts of which have been translated into English. Above all, I found that my most sustained sense of the man came from a book I had somewhat dreaded reading – his two-volume autobiography, My Life, published privately from 1870 to 1880. In the event, it turned out to be as vivacious and candid as the greatest artists’ autobiographies, every bit as compelling and stimulating as Benvenuto Cellini’s or Berlioz’s – and about as reliable. The circumstances of the book’s writing (dictated to his then mistress, Cosima von Bülow, at the behest of his besotted patron Ludwig II, edited and brought to press by an equally – at that stage – doting Nietzsche) mean that its truth is rarely pure and never simple, but it leaps off the page. At the very least, it tells us how he wanted to be seen by the world, which was by no means as a plaster saint. It is the work of a master dramatist, which is how he saw himself.

VORSPIEL

On 26 August 1876, as the last notes of the first performance of The Twilight of the Gods died away in the newly built Festspielhaus, in the tiny Bavarian town of Bayreuth, 2,000 people sat shaken, inspired, enchanted – or appalled. Among them were the musical aristocracy of Europe: Liszt, Saint-Saëns, Tchaikovsky, Anton Rubinstein, Grieg and Bruckner, along with a good sprinkling of the actual aristocracy of Europe, two emperors, three kings, a handful of princes, two grand dukes. All of them, or almost all of them, were swept along on a cataclysm of emotion to equal anything that happened on stage that evening.

As the applause grew and grew, and before singers or conductor or designer or choreographer had appeared in front of the curtain to acknowledge it, a diminutive, stooping figure, familiar not just to the faithful but to the cultured world at large, the subject of a dozen photoshoots, two dozen portraits and a thousand cartoons, made his way somewhat lopsidedly to the front of the stage; his disproportionately huge head with its madly bulging eyes was topped by a floppy velvet cap set at a rakish angle. This man, this tiny man, sixty-three years old, but looking, Tchaikovsky thought, ancient and frail, was the hero of the hour, the sole architect of the vast four-day, fifteen-hour epic, every one of whose thousands and thousands of words and thousands and thousands of notes he had created, unleashing onto the vast stage gods and dwarves, dragons and songbirds, women warriors on horseback and maidens disporting themselves in the Rhine, digging deeply and unsettlingly into the subconscious, discharging in his audience emotions that were oceanic and engulfing – this man was the architect of all that; the architect, indeed, in all but name, of the very theatre in which the heaving, roaring audience sat. There he stood before them, the self-proclaimed Musician of the Future. He held a hand up, and in the ensuing silence, in the marked Saxon accent which he never made the slightest attempt to lose, he said: ‘Now you’ve seen what I want to achieve in Art. And you’ve seen what my artists, what we, can achieve. If you want the same thing, we shall have an Art.’

That was the way he spoke.

By we, he meant, of course, the German people. The first, the most important thing he had to say, was that the great work he had brought into existence was, above all else, German.

At a celebratory banquet the following night, after an interminable and obscure speech by a Reichstag deputy, the Hungarian politician Count Albert Apponyi leaped to his feet unannounced and said:

Brünnhilde – the new national art – lay asleep on a rock, surrounded by a great fire. The god Wotan had lit this fire, so that only the victorious and finest hero, a hero who knew no fear, would win her as his bride. Around the rock were mountains of ash and clinker – the cross-breeding of our own music with non-German elements. Along came a hero, the like of whom had never been seen before, Richard Wagner, who forged a weapon from the fragments of the sword of his fathers – the classical German masters – and with this sword he penetrated the fire, and with his kiss he awoke the sleeping Brünnhilde. ‘Hail to you, victorious light!’ she cried and with her we join our voices: ‘Three cheers to our master, Richard Wagner! Hip hip! Hip hip! Hip hip!’

So that was it: Wagner was the hero of the newly unified German Reich, which had come into being just five years earlier, and his music was its music. Many people, including many Germans, felt very uncomfortable about this new Germany, and The Ring of the Nibelung seemed to embody, in its grandiosity, its self-celebrating Teutonic tub-thumping, its primitivism, everything that worried them about it. Wagner himself, after a brief and unsuccessful flirtation with the masters of the new establishment, was already somewhat unenamoured of their policies: to his immeasurable disgust, one of Reichskanzler Bismarck’s first acts had been to give the vote to Jews. Wagner also, more surprisingly, loathed the new climate of militarism and imperialism. He withdrew back into the kingdom of art where he would always be absolute monarch, where his will would always prevail, where he could explore the depths and the heights of human experience – by which he meant, of course, his own experience.

None of this – Wagner’s creation of a new national art, his acclaim as the greatest German artist of his times, the creation of his custom-built theatre – could possibly have been predicted at any point in the composer’s life up to that point. It was, to be sure, exactly what he set out to do, almost to the letter. But there was nothing inevitable about it whatever. The massive solidity of his achievement grew out of and existed in the face of profound instability, both internal and external, an instability which characterises every stage and every phase of his life and which indeed is at the very heart of his music. At every turn of the way, his vision, and he was nothing if not visionary, was in danger of being sabotaged, either by circumstances, or by other people, or – more often than not – by himself.

We know all this because he told us. We know everything about this extraordinary man, everything, that is, except the most important thing: how he created his music. Because even he, the great motor-mouth, the obsessive self-analyst, was unable to explain that. But everything else, we know. Not just because of the memoirs, the reviews, the police records, the biographies, but because, in a way unusual in a musician – almost unknown, in fact – he was driven to communicate verbally, to explain himself in conversation, in letters, in speeches, in diaries, in pamphlets, in books. He wrote about art, music, theatre, history, politics, race, language, anthropology, myth, philosophy. Above all he wrote about himself. All this self-centredness was not simple egomania, though it was that too. It was how he engaged with his creativity.

Before he could compose a note he needed to articulate his position, to formulate his philosophy, to put himself in relation to the work and to the world – to dramatise himself as an artist, one might say. And for those who were susceptible, this torrent of words and this vision of himself was bewitching – positively hypnotic. For others (including some of his closest associates) it was unnerving, dangerous, overwhelming, almost life-threatening. His production of himself was inextinguishable. Many people tried to stop him, to suppress him, to silence him. Nothing but death could stem the flow. Where did it all come from? What was going on inside Wagner’s head?

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.