Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Solomon Creed», sayfa 2

4

I stare into the heart of the fire and feel as if it’s staring back at me. But that can’t be right. I know that. The air swirls and wails and roars around me like the world is in pain.

The first fire truck stops at the edge of the blaze and people run out, pulling hose from its belly like they are drawing innards from some beast in sacrifice to a burning god. They seem so tiny and the fire so big. The wind stirs the flames and the fire roars forward, up the road, towards the men, towards me. Fear flares inside me and I turn to run and almost collide with a woman wearing a dark blue uniform, walking up the road behind me.

‘Are you OK, sir?’ she says, her eyes soft with concern. I want to hold her and have her hold me but my fear of the fire is too great and so is my desire to get away from it. I duck past her and keep on running, straight into a man wearing the same uniform. He grabs my arm and I try to pull free but I cannot. He is too strong and this surprises me, as if I am not used to being weak.

‘I need to get away,’ I say in my soft, unfamiliar voice, and glance back over my shoulder at the flames being blown closer by the wind.

‘You’re safe now, sir,’ he says with a professional calm that only makes me more anxious. How can he know I am safe, how can he possibly know?

I look back and past him towards the town and the sign, but there is a parked ambulance blocking my view and this makes me anxious too.

‘I need to get away from it,’ I say, pulling my arm away, trying to make him understand. ‘I think the fire is here because of me.’

He nods as if he understands, but I see his other hand reaching out to grab me and I seize it and pull hard, sweeping his feet from beneath him with my leg at the same time and twisting away so he falls to the ground. The movement is as natural as breathing and as smooth as a well-practised dance step. My muscles still have memory it seems. I look down into his shocked face. ‘Sorry, Lawrence,’ I say, using the name on his badge, then I turn to run – back to the town and away from the fire. I manage one step before his hand grabs my leg, his strong fingers closing round my ankle like a manacle.

I stumble, regain my balance, turn back and raise my foot. I don’t want to kick him but I will, I will kick him right in his face if that’s what it takes to make him let go. The thought of the solid heel of my foot crashing into his nose, splitting his skin and spilling blood, brings a sensation like warm air rushing through me. It’s a nice feeling, and it disturbs me as much as my earlier familiarity with the smell of death. I try to focus on something else, try to smother my instinct and stop my foot from lashing out, and in this pause something big and solid hits me hard, ripping my leg from the man’s grip.

I hit the ground and a flash of white explodes inside my skull as my head bangs against the road. Rage erupts in me. I fight to wriggle free from whoever tackled me. Hot breath blows on my cheek and I smell sour coffee and the beginnings of tooth decay. I twist my head round and see the face of the policeman who nearly ran me down. ‘Take it easy,’ he says, pinning me down with his weight, ‘they’re only trying to help you here.’

But they’re not. If they wanted to help, they’d let me go.

In a detached part of my mind I know that I could use my teeth to tear at his cheek or his nose, attack him with such ferocity he would want to be free of me more than I do from him. I am simultaneously fascinated, appalled and excited by this notion, this realization that I have the power to free myself but that something is holding me back, something inside me.

More hands grab me and press me hard to the ground. I feel a sting in my arm like a large insect has bitten me. The female medic is crouching beside me now, her attention fixed on the syringe sticking into my arm.

‘Unfair fight,’ I try to say, but am already slurring by the time I get to the last word.

The world starts turning to liquid and I feel myself going limp. A hand cradles my head and gently lowers it to the ground. I try to fight it, willing my eyes to stay open. I can see the distant town, framed by the road and sky. I want to tell them all to hurry, that the fire is coming and they need to get away, but my mouth no longer works. My vision starts to tunnel, black around the edges, a diminishing circle of light in the centre, as if I am falling backwards down a deep well. I can see the sign now past the edge of the ambulance, the words on it visible too. I read them in the clarifying air, the last thing I see before my eyes close and the world goes dark:

WELCOME TO THE CITY OF

REDEMPTION

5

Mulcahy leaned against the Jeep and stared out at the jagged lines of wings beyond the chain-link fence. From where he stood he could see a Vietnam-era B-52 with upwards of thirty mission decals on its fuselage, a World War II bomber of some sort, a heavy transporter plane that resembled a whale, and a squadron of sharp-nosed, lethal-looking jet fighters with various paint jobs from various countries, including a MiG with a Soviet star on the side and two smaller ones beneath the cockpit windows denoting combat kills.

Beyond the parade of military planes a runway arrowed away into the heart of the caldera, snakes of heat twisting in the air above it. There were some buzzards to the north, circling above something dead or dying in the desert; other than that there was nothing, not even a cloud, though he had heard thunder a while back. A spot of rain would be nice. God knows they needed it.

He checked his watch.

Late.

Sweat was starting to prick and tickle in his hair and on his back beneath his shirt as the trapped heat of the day got hold of him. The silver Grand Cherokee he was leaning against had black tinted windows, cool leather seats and a kick-ass air-conditioner circulating chilled air at a steady sixty-five degrees. He could hear the unit whirring under the idling engine. Even so, he preferred to stand outside in the desert heat than remain in the car with the two morons he was having to baby-sit, listening to their inane conversation.

– Hey, man, how many Nazis you think that bird wasted?

– How many gook babies you think that one burned up?

They’d somehow made the assumption that Mulcahy was ex-military, which, in their fidgety, drug-fried minds, also made him an expert on every war ever fought and the machines used to fight them. He’d told them, several times, that he had not served in any branch of the armed forces and therefore knew as much about war planes as they did, but they kept on with their endless questions and fantasy body counts.

He checked his watch again.

Once the package was delivered to the meeting point he could drive away, take a long, cold shower and wash away the day. A window buzzed open next to him, and super-cooled air leaked out from inside.

‘Where’s the plane at, man?’ It was Javier, the shorter, more irritating of the two men, and a distant relative of Papa Tío, the big boss on the Mexican side.

‘It’s not here,’ Mulcahy replied.

‘No shit, tell me something I don’t know.’

‘Hard to know where to start.’

‘What?’

Mulcahy took a step away from the Jeep and stretched until he felt the vertebrae pop in his spine. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘If anything was wrong I’d get a message.’

Javier thought for a moment then nodded. He had inherited some of the boss man’s swagger but none of the brains so far as Mulcahy could tell. He had also caught the family looks, which was unfortunate, and the combination of his squat stature, oily, pock-marked skin and fleshy, petulant lips made him appear more like a toad in jeans and a T-shirt than a man.

‘Shut the window, man, it’s like a motherfuckin’ oven out there.’ That was Carlos, idiot number two, not blood, as far as he knew, but clearly in good enough standing with the cartel to be allowed to come along for the ride.

‘I’m talking,’ Javier snarled. ‘I be closing the window when I’m good and ready.’

Mulcahy turned back and stared up at the empty sky.

‘What kind of plane we looking for? Is it one of these big-assed nuke bombers? Man, that would be some cool ride.’

Mulcahy considered not replying, but this was the one piece of information about aircraft he did know because it had been included in the brief. Besides, the longer he talked to Javier, the longer the window would remain open, leaking cold air out and hot air in.

‘It’s a Beechcraft,’ he said.

‘What’s that?’

‘An old airplane, I guess.’

‘What, like a private jet?’

‘Propellers, I think.’

Javier pursed his boxing-glove lips and nodded. ‘Still, sounds pretty cool. When I had to run, I sneaked across the river on some lame-assed boat in the middle of the night.’

‘You got here though, didn’t you?’

‘I guess.’

‘Well, that’s the main thing.’ Mulcahy leaned forward. A dark smudge had appeared in the sky above one of the larger spill piles on the far side of the airfield. ‘Doesn’t matter how you got here, just so long as you did.’

The smudge darkened and became a column of black smoke rising fast and thick in the sky. He heard the faint sound of distant sirens. Then Mulcahy’s phone started to buzz in his pocket.

6

Movement rocked him awake.

His eyes flickered open and he stared up at a low white ceiling, a drip bag hanging over him, a clear tube coiled round it like a translucent snake, moving gently in time with the ambulance.

‘Hey, welcome back.’ The female medic appeared over him and shone a bright light into his left eye. He felt a stab of pain and tried lifting his hand to shield his eyes but his arm wouldn’t move. He looked down and his head swam with a chemical wooziness. Thick blue nylon straps were wrapped round his arms and body, securing him tightly to the gurney.

‘For your protection while we’re on the move,’ she said, like it was no big deal. He knew the real reason. They’d had to sedate him to get him in the ambulance and the bindings were to make sure they wouldn’t need to do it again.

He hated being bound like this. It pricked at some deep emotional memory, as if he’d known confinement and never wanted to know it again. He focused on the feeling, trying to remember where it came from, but his mind remained stubbornly blank.

The movement of the ambulance was making him feel sick and so was the cocktail of smells trapped inside it – iodine, sodium bicarbonate, naloxone hydrochloride, all mixed in with sweat and smoke and sickly synthetic coconut air-freshener drifting in from the driver’s cab. He wanted to feel the ground beneath his feet again and the wind on his face. He wanted to be free to focus and think and remember what it was he had come here to do. The pain in his arm flared again at the thought and the bar rattled when he tried to reach for it.

‘Could you loosen the straps?’ He forced his voice to stay low and calm. ‘Just enough so I can move my arm.’

The medic chewed her lip and fiddled with a thin necklace round her neck with ‘Gloria’ written on it in gold letters. ‘OK,’ she said. ‘But you try anything and I’ll knock you straight out again, understand?’ She held up the penlight. ‘And you’ve got to let me do my job.’

He nodded. She paused a little longer to let him know who was in charge, then reached down and tugged at a strap by the side of the gurney. The nylon band holding his hands came loose and he lifted his arm to rub at his shoulder.

‘Sorry about that,’ Gloria said, leaning in and flashing the light in his eye again. ‘Quickest way to calm you down before you injured someone.’ The light hurt but this time he put up with it.

‘What’s your name, sir?’ She switched the light to his other eye.

She was so close he could feel her breath on his skin and it made him want to reach out and touch her to see what she felt like and make gentle rather than violent contact with someone. ‘I don’t remember,’ he said. ‘I don’t remember anything.’

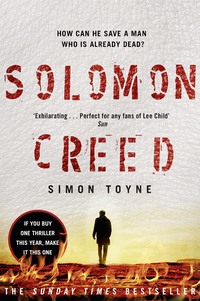

‘How about Solomon?’ a new voice answered for him, a man’s voice, high-pitched but with a touch of gravel in it. ‘Solomon Creed, that ring any bells?’

Gloria leaned down to write some notes on a clipboard and he saw the cop who had nearly run him down perched on the gurney behind her.

‘Solomon,’ he repeated, and it felt comfortable, like boots he had walked long miles wearing. ‘Solomon Creed.’ He stared at the cop, hoping he might know more than his name. ‘Do you know me?’

The cop shook his head and held up a small book. ‘Found this in your pocket, personally inscribed to a Solomon Creed, so I assume that’s you. Name’s in your jacket too.’ He nodded at the folded grey jacket lying on the gurney next to him. ‘Stitched right on the label in gold thread and written in French.’ He said French like he was spitting out something bitter.

Solomon studied the book. There was a stern, sepia-tinted photograph of a man on the cover and old-fashioned block type that spelled out the title:

RICHES AND REDEMPTION

THE MAKING OF A TOWN

A Memoir

by the Reverend Jack ‘King’ Cassidy

Founder and first citizen

He wanted to snatch the book away from the cop and see what else it contained. He didn’t recognize it. No memory of it at all. No memory of anything, but it had to be important. Frustrating. Maddening. And why had the cop been through his pockets? The thought of it made his hands clench into fists.

‘So, Mr Creed,’ the cop continued, ‘any idea why you were running away from that burning plane?’

‘I can’t remember,’ Solomon said. A badge on the cop’s shirt identified him as Chief Garth B. Morgan, hinting at Welsh ancestry and explaining why his skin was pink and freckled and clearly unsuited to this climate – like his own.

What the hell was he doing here?

‘You think maybe you were a passenger?’ Morgan asked.

‘No.’

Morgan frowned. ‘How can you be sure if you can’t remember?’

Solomon looked out of the rear window at the burning plane and a fresh torrent of information cascaded through his head and crystallized into an explanation. ‘Because of the way the wings are folded.’

Morgan followed Solomon’s gaze. One wing still stood at the centre of the blaze, folded up towards the sky. ‘What about it?’

‘They show that the aircraft flew straight into the ground. Any passengers would have been thrown downwards, not outwards – and with lethal force. A crash like that would also have caused the fuel tanks to rupture and the fuel to ignite. Aviation fuel in an open-air burn reaches between five hundred and seven hundred degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to burn flesh from bone in seconds. So, taking that into account, I could not possibly have been on that plane and still be talking to you now.’

Morgan twitched like his nose had been flicked. ‘So where did you come from, if not the plane?’

‘All I can remember is the road and the fire,’ Solomon said, rubbing at his shoulder where the pain had now settled into a steady ache.

‘Let me take a look at that,’ Gloria said, stepping closer and blocking his view of Morgan.

Solomon started undoing his buttons, watching his fingers moving, the skin as white as his shirt.

‘Back there you said something about the fire being here because of you,’ Morgan said. ‘Any idea what you meant by that?’

Solomon remembered the feeling of total fear and panic and his overpowering desire to get away from it. ‘It’s a feeling more than a memory,’ he said. ‘Like the fire is connected to me. I can’t explain it.’ He unbuttoned his cuffs, slipped his arms out of his shirt and became aware of a shift in the atmosphere.

Gloria leaned in, staring hard at Solomon’s shoulder. Morgan was staring too. Solomon followed their gaze and saw the angry red origin of his recurring pain.

‘What is that?’ Gloria whispered.

Solomon had no answer for that either.

7

‘Crashed? What do you mean crashed?’

The Cherokee was kicking up dust, Mulcahy at the wheel, eyeing the smoke rising fast to the west as they drove away from the airfield. ‘Planes crash,’ he said. ‘You know that, right? They’re kind of famous for it.’

Javier was staring out at the smoke, the obscene cushions of his lips hanging wet and open as he tried to get his head round what was happening. Carlos was in the back, hunkered down and saying nothing. His eyes were wide open and unfocused and Mulcahy knew why. Papa Tío had a reputation for making examples of people who messed things up. If the package had been lost in the crash, this package in particular, then the shit was going to hit the fan like it had been fired from a cannon. No one would be safe, not Carlos, not him, probably not even cousin Lips in the passenger seat.

‘Don’t panic,’ he said, trying to convince himself as much as anyone. ‘All we know is that a plane has crashed. We don’t know if it’s our plane or how bad it is.’

‘Looks pretty fuckin’ bad from where I’m sitting!’ Javier said, staring at the rapidly widening column of smoke.

Mulcahy’s fingers ached from gripping the wheel too tight and he forced himself to let go a little and ease off the gas. ‘Let’s wait and see what shakes out,’ he said, forcing calm into his voice. ‘For now, we follow the plan. The plane didn’t show, so we relocate to the safe house to regroup, report, and await further instructions.’

Mulcahy’s instinct was to run, put a bullet in his passengers, dump them in the desert and take off to give himself a good head start. He knew it didn’t matter that the plane crash wasn’t his fault – Papa Tío would most likely kill everyone involved anyway to send one of his famous messages. So if he killed Javier and Carlos right now then disappeared, Papa Tío would definitely think he was behind the crash, and he would never stop looking for him. Not ever. And despite his less than honourable résumé, Mulcahy didn’t especially like killing people, and he didn’t like being on the run either. He had a nice enough life, a nice enough house and a couple of women with kids and ex-husbands who weren’t looking for anything more than he could offer, and who didn’t seem to care what he did or ask how he had come by all the scars on his body. It wasn’t much in the grand scheme of things, and it was only now, when faced with the prospect of walking away from it all, that he realized how badly he wanted to keep it.

‘We stick to the plan,’ he said. ‘Anyone unhappy with that can get out of the car.’

‘And who put you in charge, pendejo?’

‘Tío did, OK? Tío called me up himself and asked me to collect this package as a personal favour to him. He also asked me to bring you two along, and like the dickhead that I am, I said “fine”. If you want to take over so all this becomes your responsibility then be my guest, otherwise shut your fat mouth and let me think.’

Javier slumped back in his seat like a teenager who’d been grounded.

Mulcahy could see flames to the west now. A twisting wall of fire curling up from the ground and spreading fast. He could see emergency vehicles, too, which meant at least the cops would be well occupied.

‘Plane!’ Javier shouted, pointing back to where they had just come from.

Mulcahy felt a flutter of hope take flight in his chest. Maybe it was all going to be OK after all. Maybe they could turn the truck around, pick up the package as arranged and have a damn good laugh about it all over some cold beers later. Maybe he would get to keep his nicely squared away, uncomplicated life after all. He took his foot off the gas and twisted in his seat, taking his eyes off the empty road for a few seconds to see what Javier had seen. He saw the bright yellow plane banking in the sky above the airfield and spun round again, stamping down hard on the gas to claw back the speed he had lost.

‘The fuck you doing?’ Javier said, looking at him like he was crazy.

‘That’s not the plane we’re waiting for,’ Mulcahy said, feeling the full weight of the situation settling back on him. ‘And it’s taking off, not landing. It’s a tanker of some sort, probably MAFFS.’

‘MAFFS? The fuck is MAFFS?’

‘They’ve been talking about them on the news ever since this dry spell set in. Stands for Modular Airborne Fire Fighting System. It’s what they use to fight wildfires.’

The chop of propellers shredded the air as the plane flew directly overhead, the sound thudding in Mulcahy’s chest.

Javier slumped back in his seat, a teenager again, shaking his head and sucking his teeth. ‘MAFFS,’ he said, like it was the worst curse word he had ever heard. ‘Tole you, you was some kind of a military motherfucker.’