Kitabı oku: «Facing the Lion», sayfa 6

I often went with Mum as she visited the neighbors. Listening carefully to the remarks of the people helped me to clear up many questions I had asked myself. Strange ideas, like the one of that pastor who tried to defend the Trinity. Trying to prove the equal might, position, and eternity of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, he said, “Take three eggs and make one omelet. It is still three eggs.”

Just as confusing to me was the idea that the soul would be judged right after death while the body was reserved for judgment at the end of the world. “When a person sins, which part commits the sin—the brain or the body? Can the body sin by itself?” The conversations started at people’s houses would continue at home around our table.

I also wanted to go alone to some farms to present a booklet about Cure for all Nations. It told about the wonderful prospect that under Christ’s rule the earth will become a paradise, no more death, no more sorrow. I had a keen desire to share this peaceful Bible message with the farmers—they were all very nice to me and gladly accepted the booklets. An hour or so later, as I returned to the village, the booklets came flying out of one house. The farmer hollered, “Doomed Bibelforscher! It’s a shame, a shame to exploit children!” Couldn’t they see that I wasn’t a child? I was eight years old! All by myself I had decided to visit those people!

I gathered up my booklets, raised my head high, and walked on, slowly repeating to myself, “The slave is not greater than his master.” I felt proud as I met the group who had called on other farms.

Why did all the Catholics say that the Bible is a Protestant book, looking at it like something damned? Later that day, Dad took a history book and sat down with me, helping me to find the true answer.

“The Bible used to be in Latin. Some Catholic priests translated it against the will of the Roman priesthood, which believed in keeping it in the Latin language. The love of its contents was stronger than the ban. Look here at that image—it shows the night of Bartholomew, the day Protestants were killed by the order of a Catholic government (August 24 and 25, 1572, when French Huguenots were massacred by Roman Catholic nobles and other citizens of Paris). During the Inquisition, the church tried to do away with its opponents. They were often burned alive, like the 15th-century Czech religious reformer John Hus and others.”

“I thought the inquisition was against the Jews.”

“It was against anyone who didn’t think according to the church teaching.”

I came to love our little Bibelforscher congregation. I had two young playmates, André Schoenaur and Edmund Schaguiné. I also gained a surrogate grandpa—Mr. Huber, a retired engineer who was a widower. He was a white-haired, well-mannered, fatherly man with a golden chain attached to a watch in his vest pocket. Marcel Graf was an office clerk at the potassium mines—tall, bald, and a real talker. The Zinglé couple often wore knickers because they were Swiss mountain climbers. Mr. Lauber, a widowed father of two small children, had lost one leg in the war. He faithfully attended all activities of the congregation, coming with his five-year-old Jeannette sitting behind him on a very old bike. There were the Dossmanns, whose son was in the Paris office of Jehovah’s Witnesses, and some others coming from outside the city.

Mum, with her missionary spirit, played a big part in the group’s activities, visiting many families, helping people like the Saler family to live a better life, getting them out of their needy situations. She believed not only in teaching but doing charitable work. Among the people she visited was Martina Ast, the lively 20-year-old maid of a Jewish family who owned the Galerie Lafayette, the main department store in Mulhouse. I loved to go visit her. She always had interesting Bible questions, but she also had nice pastries! She would even play with me sometimes.

Among our many friends, one couple was really special—the Koehls. One day when they were to be our guests, I eagerly waited for them at the window. They came in spite of the freezing weather. Adolphe, a barber, with the same name as my father, gently held his wife Maria’s elbow with one hand, and led their dog by the leash with the other. Maria’s hands were tucked in a fur muff that matched her silver fox collar. Both looked like they had just stepped out of a fashion magazine. Seated in our little salon, the two Adolphes got into a spirited conversation. Meanwhile, Mum and Maria exchanged recipes in the kitchen. After I played Maria’s favorite song, “La Paloma,” on the piano, Mum told me to serve the tea. My ears navigated between the two groups. But for some reason the left ear was “bigger” than the right. It stretched toward the two Adolphes.

“Who does he think he is—a god?” one said to the other.

“He’s just a puppet in the hands of the demons,” the other answered.

“He claims himself to be Germany’s savior—Heiland. He’s just a worm.”

“A very harmful worm, one made of rotten material.”

“He goes from victory to victory.”

“He does, but he will never prevail over Jehovah’s Witnesses.”[7] I just wondered who was this “he” that they were speaking about. In the center of the conversation was a book that our visitors had brought, Crusade Against Christianity.[8] They had it open to a drawing of some kind of camp.

“The information we learn from this book is very important. It will help us to become cautious like a serpent, and yet innocent like a dove,” both Adolphes agreed.

As the Koehls departed, they left behind the perfume of their barbershop. But they also left a big emptiness. I somehow felt that I now had another set of parents.

I returned to Bergenbach with Aunt Eugenie, who had decided not to come to our place anymore. I noticed that Grandma was treating me very differently from the way she treated Angele. She put me to work. “You are old enough to go down to the village to get our two loaves of bread.” Skipping joyfully downhill, I wondered if I had sprouted invisible wings.

Strangely, everyone in the village seemed to whisper as I went by. “Isn’t she quite little?” Quite little? My cousin—she was the one who was quite little, almost two months younger. But I had grown overnight like mushrooms do, and my Grandma recognized it. So did the cows. I had to lead them to the pasture ground, enjoying the music of their different bells. The cows could see that I wasn’t little anymore. Why couldn’t people see that I was a big girl?

But struggling back up the hill with two fresh-baked five-pound loaves, I wished I hadn’t grown so fast. I had to put my hands under the straps of my rucksack because of the burning hot loaves and the blazing sun. A few times I had to put down my load altogether. The babbling of the brook called to me, tempting me to come and cool off. But in my head I heard Mum’s warning: “When you’re sweating, never cool off your feet or you’ll get sick. Look at my arthritic feet and hands—that’s how I got them.”

Facing that steep path leading up to the farm, I could have cried. But when I heard the dogs barking, the chickens squawking, and the gurgling of the fountain, I had renewed energy. I stuck my nose in the air when I saw my little cousin, who hadn’t grown overnight as I had.

Grandma was more irritable and melancholy with each passing day. Aunt Valentine, her favorite daughter, would soon depart for Cusset, near Vichy, where Aunt Valentine’s husband had found an apartment.

Even Aunt Eugenie had no riddles, no games, no songs for us anymore. When my aunt’s employers, the Koch family, also moved to France, to the safety of the intérieur, Grandma ordered Aunt Eugenie: “You stay here! There’s nothing for you in France!”

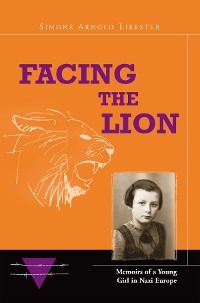

Angele and Simone, “The Oath” 1938

Angele and Simone, “The Oath” 1938

Rumors about war filled the air. Grandpa didn’t believe in war; Grandma did. Downstairs, the conversation among the four women flared up again.

“Angele, don’t worry. My father can stop a war. He says that to stop it, just take away men’s uniforms and let them go around in their underwear.” We both were sure that remedy would work!

The last family gathering was one of broken hearts around a festive dinner table. It didn’t affect Angele and me. We had a solemn ceremony to perform in the afternoon. Once more we went to the attic, putting on our dresses, ladies’ shoes of the last century, ribbons and laces to perform a sacred vow. It was in this attic that we had learned a lot from those stacks of yellowed newspaper stories, novels, happy ones, sad ones, and even Inquisition dramas. But those were over now. It was a time to make a solemn vow to keep faithful to each other. We promised to exchange our dolls’ homework by mail.

Downstairs, the conversation among the four women heated up.

“Bibelforscher are Communist agents!” Grandma shouted.

“You must earn lots of money running around like you do,” Valentine yelled.

“Yes, for that you have good feet,” added Aunt Eugenie. “You fool! You only make those American leaders rich,” Aunt Valentine said sarcastically.

“You are paid by the Jewish world power and are undermining the Church,” said Aunt Eugenie.

With a threatening voice, Grandma said emphatically: “If you want to stay a member of the family, you keep away from that sect.” Aunt Valentine, Aunt Eugenie, and Grandma kept up the attack of words.

All of a sudden, I bolted downstairs and burst into the room. “You are all mean, unfair liars!” I screamed.

Mother interrupted me, leading me outside by the hand.

“Go play in the barn; this is none of your business!” she said, calling Angele out. My curly-haired cousin was all inflamed by what she had heard.

“I’m not going to play with a heathen!”

“I’m a Christian!”

“You’re a heathen!”

“I’m...”

Mother had to separate us. Angele went back into the house singing her favorite song, the French national anthem, the Marseillaise. This kindled my Grandma’s uncontrolled temper even more.

“Dad just went down to Krüth to see your godfather. Go with him,” Mum ordered. What a good idea! I loved being with my godfather. He was such a gentle man, and so brave. He had a nice garden and fruit trees, and my cousin Maurice wasn’t at home anymore. I could enjoy myself in peace.

Godfather’s plums tasted like honey. I went up to the window and looked inside. On the table, I could see two glasses with a little Kirschenwasser, cherry liqueur, and a book, a gift Dad had brought along.

“Take this away or I’ll burn it!”

“But it’s a Catholic Bible.”

“Anyone can say that!”

“I’ll show you,” Dad said, taking the Bible. “Look, here it says the same thing as in the gospel reading at the church. The problem is that they read it but don’t apply it.”

My gentle godfather jumped to his feet and turned stiff like a statue. He threw the Bible outside and pointed to the door. Dad got up slowly, white and speechless. Godfather grabbed Dad by the belt and threw him out of the front door. As I came around the front of the house, I saw it happen. My father had glassy eyes and stood there without saying a word.

“I never should have raised you! Never will you see my face anymore unless you repent and come with me to confess and take Communion in my presence. Don’t send Emma or Simone to see me. As long as you don’t return to church, your family doesn’t exist anymore! You will be doomed!”

We were in danger of being killed with an ax by Mr. Eguemann in Dornach. We were the constant target of the parish priest, who crossed the street just to spit at Mother’s feet, even when I was with her. Now, being outcasts from both parental homes made us feel like we were really “doomed!”

FALL 1938

My parents searched for reconciliation without compromising. But didn’t our relatives make the price out of reach? How could we possibly fake our return to church just to appease them without sacrificing peace in our hearts? How could we deny Bible truth? After many efforts to talk with them, it became very clear that they were unmovable. To open their doors and their hearts to us, they demanded that we had to return to church.

Dad concluded, “I cannot act against my conviction, or I would be a hypocrite!”

And Mother said: “Even if my mother casts me out for getting baptized, I’ve already made the vow. I’ll do it, no matter the cost.”

The Witnesses held a convention in Basel that autumn. Standing next to the pool in Basel, I was cuddled up in Dad’s arms, feeling sad because the baptism wasn’t for me, still a “young child”! Dad held me close. I could sense his deep emotions as Mother stepped into the pool. Then a tear came down his cheek and he whispered, “It is accomplished.” Looking at me, he added, “From now on, your mother will put God before everyone else, dying for him if necessary.”

“And you, Daddy?”

“I’m not ready yet.”

Later, I asked, “Mum, what does he mean, ‘I’m not ready yet’? Doesn’t Dad love God?”

“Your father takes everything seriously; he has very high standards. As soon as he is baptized, he will also take on heavy responsibilities in the congregation. He feels that he is not ready for that yet.” Was it because it looked like there might be a war?

Hitler’s demand of autonomy for Germans in the Sudeten region precipitated an international crisis. At the Munich Conference, September 28 and 29, 1938, the leaders of France, Great Britain, and Italy met with Hitler. As a result, the Sudetenland was annexed by Germany on October 10, 1938.

During the Sudeten conflict, Dad had accepted a military noncombatant assignment. He was stationed at the Mulhouse post office, monitoring telephone conversations. I didn’t understand how the telephone worked—we didn’t have one—only the rich had telephones. I decided that Dad had to catch words coming along an electric wire.

Even though the danger of war had subsided, tension still hung in the air. Dad had come home and put on his civilian clothes, but, he fell silent just like before. His appetite was gone. Zita couldn’t get his attention. The days grew shorter, the leaves started to turn brown, and we felt more and more gloomy. Was it because we felt like outcasts from our family?

Maybe our relatives thought that this isolation would bring us back to our senses and make us return to the Catholic Church. But how could we ever go against our conscience? My parents were determined to stick to the Bible. The small congregation of Bibelforscher filled our needs. They had become close and dear to us.

The main street leading to the railroad station of Mulhouse followed alongside a square garden. It was surrounded by arches that cast a cool shadow upon the sidewalks. In the nice shade, we could stroll along the row of shops. Among the boutiques was a barbershop with three armchairs and three waiting chairs. The place belonged to Dad’s barber, his close friend, Adolphe Koehl. He was going to become my barber, too.

Nearing the shop, I could smell a delightful aroma of eau de cologne floating over the sidewalk. Opposite the entrance a big curtain separated the salon from the service room. It was a little place with a table piled up with towels; one chair was in front of it and a stool was underneath it. Between the last steps of a winding staircase going up to the apartment and a door leading out to the inner courtyard, there was just enough room for three people. Every Thursday was children’s haircut day, the day the two Adolphes chose to meet. I got my haircut at the same time. It was easier for Adolphe to leave his employee to tend the shop by himself on that day. Children seldom asked for the owner himself. That was not the case with his most select clients: doctors, judges, managers, and so on. Many asked to be groomed by the gentlemanly owner who had such a charming personality.

On Adolph Koehl’s face, a sharp-cut little black brush moustache underlined a well-sculpted nose that carried a bold forehead with overgrown edges. Behind his black wild eyebrows, sparkling sapphire eyes flashed with meaning. His fine lips spoke cheerful words, practical wisdom, and humor. The man behind the face was slender and nimble. His wife, Maria, standing beside him, was even smaller, her presence almost imperceptible. She had a welcoming smile on her lips when she greeted the clients. Maria reminded me of one of those painted Chinese ladies on our teacups. Her husband said jokingly: “She is so frail that a breath would tip her over!”

After he groomed both of us, Mr. Koehl would take Dad behind the curtain. I’d sit on one of the chairs, the one nearest to their conversation to make sure I could get some scraps out of their undertone exchange. I always had my weekly Mickey Mouse magazine to read. I also used it to hide my face whenever a client turned to look at me in the huge mirror that covered the wall in front of me. I could hide behind it when I would see Mr. Koehl’s finger moving the edge of the curtain back just a bit to check on happenings in the shop while he himself kept out of sight. When Dad subscribed to the “Mickey Mouse” journal for me, he said: “You are a serious little girl, far too serious for your age. But life is also made of fun and laughter. Learn to laugh, Simone. Look closely at the drawings; they tell you a lot more than the words! We’ll have some fun together!”

It had become a semimonthly habit. Thursday, my day off from school, was the day my journal arrived in the mail. It was also the day for the barber. Adolphe’s place became a source of encouragement and a well of practical counsel.

I heard Dad’s weary voice as he complained to the barber, “Those long hours alone, listening to the telephone conversations, wearing my heavy khaki outfit, made me feel uncomfortable. My conscience has been in a turmoil,” Dad confessed, “and I asked myself if any apostle would have done what I did.”

My father’s confusion was very troubling to me. How could he act against his conscience, he who constantly insisted on the need to be at peace with oneself? Why didn’t he follow his own prescription for peace: ‘Stop the war by making everyone walk around in their underwear!’

“Do you believe the first Christians would have performed activity like I did?” The barber’s answer was inaudible, but I said to myself, “There cannot be anything wrong with catching traveling words!”

“For sure the first Christians didn’t fight in the Roman Army!”

Behind my “three little pigs” story, I agreed. Mademoiselle had told us in school how a Roman soldier had quit the army and was sentenced to the arena. Finally I understood Mr. Koehl: “It is not easy to find out what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God. We have to pay the things to Caesar but also the things to God. This is a personal decision.”

My parents never told me that there is a Caesar today, I thought. I never heard it in school either. I knew about the King of England, the French President, the German Führer, the Duke in Italy, the Spanish Caudillo, and wondered where Caesar lived.

The Threat of War

CHAPTER 4

The Threat of War

„G

randpa, are you still sure that we aren’t going to have a war?”

“Hard to say, but I hope not.” After a silence, he said bleakly, “Who knows? The nations are so fickle!”

“But Grandpa, you said...”

“Yes, yes, I know I said, but, Simone, even priests have fought in Catholic Spain!”

“I saw a picture somewhere with priests in their long robes standing behind cannons.”

“I did too. Maybe it was in Consolation.” Consolation was the magazine of the Bibelsforcher.

“Grandpa, you read Consolation?”

“Your mum subscribed for me, and since I go to the village to get the bread I also pick up the mail. So I put the magazine in a hiding place,” adding in an undertone, “I’ll show it to you.” His red mustache twitched as he whispered: “It’s there by the toilet.” After a long pause, his mustache moved again and he said: “If your grandma ever found out, oh, my!”

He suddenly became very serious. “She is working in the farthest field today. I’m surprised that she didn’t drag you along. Lately she really loads you down with work, you poor kid!”

“But I love it! I’m a big girl, Grandpa!”

Grandfather got up and went over to the milk cupboard. I told him that I had walked along the former French-German border up on Felleringerkopf and the Drumont Mountain but this time I had not seen any skull.

“A skull?” Grandfather asked while carefully taking down a large bowl of the morning milk. He took a piece of bread and swished it around in the cream. His mustache pointed upward, his eyes narrowing to slits. Putting the bowl back, he said jokingly, “This is Grandma’s Most Holy. No one else has the right to touch, eat, and enjoy it. If she comes, you’ll have to disappear through the window in the back!” Putting one finger to his lips, he added, “I’ll steal some more.”

He took another bowl. “You see, in this glass bowl I have some leftover Muenster cheese. I’ll put some cream on it, cover the bowl, and put it in a secret sunny place to let it ferment. One day we will have it together when Grandma is not around. Don’t be afraid. She is like an old hag; she always finds out my mischief. When the thunderstorm breaks out, I just let it go by.”

His blue eyes opened wide, and his mustache turned down-ward. He said with a conspiratorial voice, “As soon as I can, I just start off again!” My wonderful grandpa! But he asked again, “Now, what’s this about a skull?”

“Our class went for an outing to the mountain that you can see from our balcony. You know, it has a blinking light at night.” Grandpa seemed to know about it.

He said, “People say it is for secret war communication.”

“What’s the name of the place?” I asked.

“It’s the Hartmann’s Willerkopf.”

“Have you been there?”

“No, but it was the site of the greatest battle between the French and the Germans during the Great War, killing thousands. It was called the Verdun of Alsace.”[9]

“Grandpa, why isn’t there a forest anymore? We had a hard time finding some shade to eat our lunch.”

“War kills more than men; it kills all the vegetation too.”

“You know, we saw a rusty helmet right by where we were sitting. And when I went to have a closer look, I found a skull inside it. Grandpa, tell me—was he young? Did he have children? How did he die—by bullet or by bayonet? Was he French or German? Catholic or Protestant? Who was he?”

“It doesn’t really matter, Little One. He was just a man.”

“Grandpa, you know what the Catholics say? If it’s a Frenchman, he’s up in heaven.”

“Little One, you know they said just the opposite during the Great War.”

“Grandpa, I know he will be resurrected. He’s just sleeping.”

Grandpa looked up to heaven and shrugged. I could feel his breath on me as he heaved a sigh. After a long silence, he finally opened one of his jars filled with cheese, inhaling with delight the escaping aroma.

“Doesn’t it taste wonderful?” Grandpa asked. The cheese had ripened, and we had our secret snack and little chat. True, it smelled awful to me, but what a creamy taste! And above all what excitement—all of this behind Grandma’s back!

“Grandpa, why does Grandma always grumble every evening when you listen to the news?”

“She hates that radio your parents gave her.”

“But why?”

“She is against anything new, things her parents didn’t use. She was upset when we got electricity. We had the first mountain power line. I was in charge of the community and had decided we should have a light at the crossroads of the two paths and another light near the little mountain river. Grandma’s uncle had missed the little bridge there one night. He fell into the ice-cold water and died. But even so, Grandma didn’t want to have the light inside the house. ‘Fire on a wire does not come in,’ she said. And she still won’t have it in places she can’t supervise, like the attic or the basement. That’s why you see her going around with her candle holder. ”

“But candles are dangerous, Grandma always claims.”

“Of course, but she has it in her hands. That makes her feel safe. You know, we’ve been raised with candlelight or petroleum lamps, and we still use them during bad storms.”

“My dad said that one day we will have pictures on the radio.”

“I don’t know if that will ever be possible. Your dad reads a lot and tells you many things. Do you understand what he says?”

“It will be like a movie.”

“I never saw a movie. The shows are down in the city on evenings during our milking time. People say it is very interesting. Your mum wanted to help when the “Photodrama of Creation”[10] movie was shown in Mulhouse, but the night train didn’t come up as far as Oderen in those days.”

“I have the printed movie at home,” I said. “It was given to me by a traveling brother.”

“Who’s that?” asked Grandpa.

“A man who goes from city to city visiting the Kingdom Halls and giving talks.”

“Did you say ‘brother’?”

“Everyone who is baptized is a brother or a sister, because God is our Father in heaven.”

“This man, is he like our African missionary priest?” Grandpa asked between bites.

“No, he’s a man like you. He doesn’t wear special clothes; he doesn’t ask for money for a mission. We never pass a plate at the meeting hall for alms. You know, he ate with us!”

“He did?” mumbled Grandpa.

“It was fun! Mum had asked him what he had not eaten for a long time and what he would like to have. At first he said, ‘Anything,’ but Mum insisted. He finally told her that he ate homemade noodles and rabbit all the time. He would enjoy having some fish. Mum bought a big live carp and let it swim in our bathtub. I played with it all evening trying to catch it!”

“And you couldn’t!”

“Well, the following day the brother came to kill it and prepare it. Mum took me away. We heard him splashing in the water—he was playing, too. Suddenly there was a big ‘ploof.’ Mother ran; I followed. The brother had landed in the bathtub, and the carp was on the floor, beating the tile with its tail.

“Quick, jump out the window!” Grandpa whispered excitedly, “and take along the jar. Grandma is coming!” The window was only a foot above the meadow. With my heart beating, I jumped out the window and hid behind the apple tree. Grandma stepped in, her nose was twitching like a rabbit’s; big wrinkles formed high up on her forehead—the thunderstorm was building up. Her face was upside down, and the storm broke out. Grandpa sat on his chair, pulled his shoulders up to hide his head, bent over, and waited until the torrent of mean words was over. When he saw me again, his smiling face looked like a bright sun. And with a twinkle in his eye, my dear Grandpa whispered, “We’ll do it again, won’t we?” Oh! my wonderful grandpa!

Listening to the news on the radio became a very serious matter. Everyone sat there with a religious silence. Grandma accused the French of provoking a war. Grandpa in turn said it was Germany’s fault. The arguments at the table started up again about Danzig, Poland, Albania, and the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria by Germany on March 13, 1938). Looking at me, Grandpa said, “That’s far from here, Simone. Don’t worry.”

Grandma believed there would be a war. She had Uncle Germain bring some groceries home every evening. Loaded down, he came home from his hard work in the quarry completely exhausted. Grandma went with him to a secret place to hide the food that he had carried with so much difficulty. I could feel the depth of my family’s despair from my grandparents’ war stories, the subject of their daily supper conversation.

“Grandpa, are you sure we won’t have a war?”

He took me over to the bench that perched on the promontory rock and pointed to a barren mountain top across the valley. “You see that big solitary tree over there from the Gummkopf?”

Of course I saw it; everyone from far away could see it.

“Somebody from my family planted it back in those postwar years of the 1870s; it is a ‘peace tree.’ It grew, but sad to say, peace didn’t grow. The tree lived through the Great War. It’s still there, and it may witness another war. My parents have seen two wars in less than a man’s lifetime!”[11]

“Grandpa, will we have a war?”

“We might.”

“Will it be here?”

“Who knows? They built a strong defense alongside the Rhine River—the Maginot Line!”[12]

“Do children get killed?”

“Everybody is in danger when weapons are fired, but maybe we will be spared.”

“Grandpa, everyone goes to war?”

“The men from 20 to 40 years old are called up.”

“All the men want to make war? That’s awful!”

“Oh, no, no! They do not want to, but they have to.”

“Why?”

“Because the state is sovereign, above anything in the world.”

“What’s that?”

“It means that the government is above all. It has the last word. It has the right to declare war, and the right to make peace; it has the sword—that is, the right to kill.”

“Grandpa, tell me the truth. Will the Alsatians go to war against Germany? Dad told me it is our fatherland, and France our motherland.”

“Some Alsatians will open their doors eagerly to the Germans. The situation here is difficult indeed. Ask your dad. He will tell you that his brother, Materne, was in the German army. So was I before the Great War, the world war. Then suddenly, in the beginning of the war, the French arrived over the border where you went to pick blueberries the other day, and they deported all the remaining males to southern France.”

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.