Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Gravity»

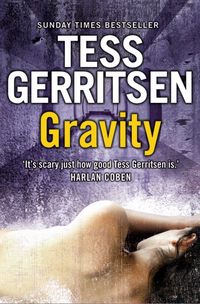

Gravity

Tess Gerritsen

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in the USA by Pocket Books 1999

Copyright © Tess Gerritsen 1999

Tess Gerritsen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006513087

Ebook Edition © JULY 2011 ISBN: 9780007370795

Version: 2016-10-05

To the men and women whohave made spaceflight a reality.

Mankind’s greatest achievements are launched on dreams.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

THE SEA

1

THE LAUNCH

2

3

4

5

6

THE STATION

7

8

THE SICKNESS

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

THE AUTOPSY

16

17

18

THE CHIMERA

19

20

21

22

23

24

THE ORIGIN

25

26

27

THE SEA

28

GLOSSARY

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

TESS GERRITSEN

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

THE SEA

1

The Galápagos Rift

.30 Degrees South, 90.30 Degrees West

He was gliding on the edge of the abyss.

Below him yawned the watery blackness of a frigid underworld, where the sun had never penetrated, where the only light was the fleeting spark of a bioluminescent creature. Lying prone in the form-fitting body pan of Deep Flight IV, his head cradled in the clear acrylic nose cone, Dr Stephen D. Ahearn had the exhilarating sensation of soaring, untethered, through the vastness of space. In the beams of his wing lights he saw the gentle and continuous drizzle of organic debris falling from the light-drenched waters far above. They were the corpses of protozoans, drifting down through thousands of feet of water to their final graveyard on the ocean floor.

Gliding through that soft rain of debris, he guided Deep Flight along the underwater canyon’s rim, keeping the abyss to his port side, the plateau floor beneath him. Though the sediment was seemingly barren, the evidence of life was everywhere. Etched in the ocean floor were the tracks and plow marks of wandering creatures, now safely concealed in their cloak of sediment. He saw evidence of man as well: a rusted length of chain, sinuously draped around a fallen anchor; a soda pop bottle, half-submerged in ooze. Ghostly remnants from the alien world above.

A startling sight suddenly loomed into view. It was like coming across an underwater grove of charred tree trunks. The objects were blacksmoker chimneys, twenty-foot tubes formed by dissolved minerals swirling out of cracks in the earth’s crust. With the joysticks, he maneuvered Deep Flight gently starboard, to avoid the chimneys.

‘I’ve reached the hydrothermal vent,’ he said. ‘Moving at two knots, smoker chimneys to port side.’

‘How’s she handling?’ Helen’s voice crackled through his earpiece.

‘Beautifully. I want one of these babies for my own.’

She laughed. ‘Be prepared to write a very big check, Steve. You spot the nodule field yet? It should be dead ahead.’

Ahearn was silent for a moment as he peered through the watery murk. A moment later he said, ‘I see them.’

The manganese nodules looked like lumps of coal scattered across the ocean floor. Strangely, almost bizarrely, smooth, formed by minerals solidifying around stones or grains of sand, they were a highly prized source of titanium and other precious metals. But he ignored the nodules. He was in search of a prize far more valuable.

‘I’m heading down into the canyon,’ he said.

With the joysticks he steered Deep Flight over the plateau’s edge. As his velocity increased to two and a half knots, the wings, designed to produce the opposite effect of an airplane wing, dragged the sub downward. He began his descent into the abyss.

‘Eleven hundred meters,’ he counted off. ‘Eleven fifty…’

‘Watch your clearance. It’s a narrow rift. You monitoring water temperature?’

‘It’s starting to rise. Up to fifty-five degrees now.’

‘Still a ways from the vent. You’ll be in hot water in another two thousand meters.’

A shadow suddenly swooped right past Ahearn’s face. He flinched, inadvertently jerking the joystick, sending the craft rolling to starboard. The hard jolt of the sub against the canyon wall sent a clanging shock wave through the hull.

‘Jesus!’

‘Status?’ said Helen. ‘Steve, what’s your status?’

He was hyperventilating, his heart slamming in panic against the body pan. The hull. Have I damaged the hull? Through the harsh sound of his own breathing, he listened for the groan of steel giving way, for the fatal blast of water. He was thirty-six hundred feet beneath the surface, and over one hundred atmospheres of pressure were squeezing in on all sides like a fist. A breach in the hull, a burst of water, and he would be crushed.

‘Steve, talk to me!’

Cold sweat soaked his body. He finally managed to speak. ‘I got startled—collided with the canyon wall—’

‘Is there any damage?’

He looked out the dome. ‘I can’t tell. I think I bumped against the cliff with the forward sonar unit.’

‘Can you still maneuver?’

He tried the joysticks, nudging the craft to port. ‘Yes. Yes.’ He released a deep breath. ‘I think I’m okay. Something swam right past my dome. Got me rattled.’

‘Something?’

‘It went by so fast! Just this streak—like a snake whipping by.’

‘Did it look like a fish’s head on an eel’s body?’

‘Yes. Yes, that’s what I saw.’

‘Then it was an eelpout. Thermarces cerberus.’

Cerberus, thought Ahearn with a shudder. The three-headed dog guarding the gates of hell.

‘It’s attracted to the heat and sulfur,’ said Helen. ‘You’ll see more of them as you get closer to the vent.’

If you say so. Ahearn knew next to nothing about marine biology. The creatures now drifting past his acrylic head dome were merely objects of curiosity to him, living signposts pointing the way to his goal. With both hands steady at the controls now, he maneuvered Deep Flight IV deeper into the abyss.

Two thousand meters. Three thousand.

What if he had damaged the hull?

Four thousand meters, the crushing pressure of water increasing linearly as he descended. The water was blacker now, colored by plumes of sulfur from the vent below. The wing lights scarcely penetrated that thick mineral suspension. Blinded by the swirls of sediment, he maneuvered out of the sulfur-tinged water, and his visibility improved. He was descending to one side of the hydrothermal vent, out of the plume of magma-heated water, yet the external temperature continued to climb.

One hundred twenty degrees Fahrenheit.

Another streak of movement slashed across his field of vision. This time he managed to maintain his grip on the controls. He saw more eelpouts, like fat snakes hanging head down as though suspended in space. The water spewing from the vent below was rich in heated hydrogen sulfide, a chemical that was toxic and incompatible with life. But even in these black and poisonous waters, life had managed to bloom, in shapes fantastic and beautiful. Attached to the canyon wall were swaying Riftia worms, six feet long, topped with feathery scarlet headdresses. He saw clusters of giant clams, white-shelled, with tongues of velvety red peeking out. And he saw crabs, eerily pale and ghostlike as they scuttled among the crevices.

Even with the air-conditioning unit running, he was starting to feel the heat.

Six thousand meters. Water temperature one hundred eighty degrees. In the plume itself, heated by boiling magma, the temperatures would be over five hundred degrees. That life could exist even here, in utter darkness, in these poisonous and superheated waters, seemed miraculous.

‘I’m at six thousand sixty,’ he said. ‘I don’t see it.’

In his earphone, Helen’s voice was faint and crackling. ‘There’s a shelf jutting out from the wall. You should see it at around six thousand eighty meters.’

‘I’m looking.’

‘Slow your descent. It’ll come up quickly.’

‘Six thousand seventy, still looking. It’s like pea soup down here. Maybe I’m at the wrong position.’

‘…sonar readings…collapsing above you!’ Her frantic message was lost in static.

‘I didn’t copy that. Repeat.’

‘The canyon wall is giving way! There’s debris falling toward you. Get out of there!’

The loud pings of rocks hitting the hull made him jam the joysticks forward in panic. A massive shadow plummeted down through the murk just ahead and bounced off a canyon shelf, sending a fresh rain of debris into the abyss. The pings accelerated. Then there was a deafening clang, and the accompanying jolt was like a fist slamming into him.

His head jerked, his jaw slamming into the body pan. He felt himself tilting sideways, heard the sickening groan of metal as the starboard wing scraped over jutting rocks. The sub kept rolling, sediment swirling past the dome in a disorienting cloud.

He hit the emergency-weight-drop lever and fumbled with the joysticks, directing the sub to ascend. Deep Flight IV lurched forward, metal screeching against rock, and came to an unexpected halt. He was frozen in place, the sub tilted starboard. Frantically he worked at the joysticks, thrusters at full ahead.

No response.

He paused, his heart pounding as he struggled to maintain control over his rising panic. Why wasn’t he moving? Why was the sub not responding? He forced himself to scan the two digital display units. Battery power intact. AC unit still functioning. Depth gauge reading, six thousand eighty-two meters.

The sediment slowly cleared, and shapes took form in the beam of his port wing light. Peering straight ahead through the dome, he saw an alien landscape of jagged black stones and bloodred Riftia worms. He craned his neck sideways to look at his starboard wing. What he saw sent his stomach into a sickening tumble.

The wing was tightly wedged between two rocks. He could not move forward. Nor could he move backward. I am trapped in a tomb, nineteen thousand feet under the sea.

‘…copy? Steve, do you copy?’

He heard his own voice, weak with fear: ‘Can’t move—starboard wing wedged—’

‘…port-side wing flaps. A little yaw might wiggle you loose.’

‘I’ve tried it. I’ve tried everything. I’m not moving.’

There was dead silence over the earphones. Had he lost them? Had he been cut off? He thought of the ship far above, the deck gently rolling on the swells. He thought of sunshine. It had been a beautiful sunny day on the surface, birds gliding overhead. The sea a bottomless blue…

Now a man’s voice came on. It was that of Palmer Gabriel, the man who had financed the expedition, speaking calmly and in control, as always. ‘We’re starting rescue procedures, Steve. The other sub is already being lowered. We’ll get you up to the surface as soon as we can.’ There was a pause, then: ‘Can you see anything? What are your surroundings?’

‘I—I’m resting on a shelf just above the vent.’

‘How much detail can you make out?’

‘What?’

‘You’re at six thousand eighty-two meters. Right at the depth we were interested in. What about that shelf you’re on? The rocks?’

I am going to die, and he is asking about the fucking rocks.

‘Steve, use the strobe. Tell us what you see.’

He forced his gaze to the instrument panel and flicked the strobe switch.

Bright bursts of light flashed in the murk. He stared at the newly revealed landscape flickering before his retinas. Earlier he had focused on the worms. Now his attention shifted to the immense field of debris scattered across the shelf floor. The rocks were coal black, like magnesium nodules, but these had jagged edges, like congealed shards of glass. Peering to his right, at the freshly fractured rocks trapping his wing, he suddenly realized what he was looking at.

‘Helen’s right,’ he whispered.

‘I didn’t copy that.’

‘She was right! The iridium source—I have it in clear view—’

‘You’re fading out. Recommend you…’ Gabriel’s voice broke up into static and went dead.

‘I did not copy. Repeat, I did not copy!’ said Ahearn.

There was no answer.

He heard the pounding of his heart, the roar of his own breathing. Slow down, slow down. Using up my oxygen too fast…

Beyond the acrylic dome, life drifted past in a delicate dance through poisonous water. As the minutes stretched to hours, he watched the Riftia worms sway, scarlet plumes combing for nutrients. He saw an eyeless crab slowly scuttle across the field of stones.

The lights dimmed. The air-conditioning fans abruptly fell silent.

The battery was dying.

He turned off the strobe light. Only the faint beam of the port wing light was shining now. In a few minutes he would begin to feel the heat of that one-hundred-eighty-degree magma-charged water. It would radiate through the hull, would slowly cook him alive in his own sweat. Already he felt a drop trickle from his scalp and slide down his cheek. He kept his gaze focused on that single crab, delicately prancing its way across the stony shelf.

The wing light flickered.

And went out.

THE LAUNCH

2

July 7

Two Years Later

Abort.

Through the thunder of the solid propellant rocket boosters and the teeth-jarring rattle of the orbiter, the command abort sprang so clearly into Mission Specialist Emma Watson’s mind she might have heard it shouted through her comm unit. None of the crew had, in fact, said the word aloud, but in that instant she knew the choice had to be made, and quickly. She hadn’t heard the verdict yet from Commander Bob Kittredge or Pilot Jill Hewitt, seated in the cockpit in front of her. She didn’t need to. They had worked so long together as a team they could read each other’s minds, and the amber warning lights flashing on the shuttle’s flight console clearly dictated their next actions.

Seconds before, Endeavour had reached Max Q, the point during launch of greatest aerodynamic stress, when the orbiter, thrusting against the resistance of the atmosphere, begins to shudder violently. Kittredge had briefly throttled back to seventy percent to ease the vibrations. Now the console warning lights told them they’d lost two of their three main engines. Even with one main engine and two solid rocket boosters still firing, they would never make it to orbit.

They had to abort the launch.

‘Control, this is Endeavour,’ said Kittredge, his voice crisp and steady. Not a hint of apprehension. ‘Unable to throttle up. Left and center MEs* went out at Max Q. We are stuck in the bucket. Going to RTLS abort.’

‘Roger, Endeavour. We confirm two MEs* out. Proceed to RTLS abort after SRB burnout.’

Emma was already rifling through the stack of checklists, and she retrieved the card for ‘Return to Launch Site Abort.’ The crew knew every step of the procedure by heart, but in the frantic pace of an emergency abort, some vital action might be forgotten. The checklist was their security blanket.

Her heart racing, Emma scanned the appropriate path of action, clearly marked in blue. A two-engine-down RTLS abort was survivable—but only theoretically. A sequence of near miracles had to happen next. First they had to dump fuel and cut off the last main engine before separating from the huge external fuel tank. Then Kittredge would pitch the orbiter around to a heads-up attitude, pointing back toward the launch site. He would have one chance, and only one, to guide them to a safe touchdown at Kennedy. A single mistake would send Endeavour plunging into the sea.

Their lives were now in the hands of Commander Kittredge.

His voice, in constant communication with Mission Control, still sounded steady, even a little bored, as they approached the two-minute mark. The next crisis point. The CRT display flashed the Pc<50 signal. The solid rocket boosters were burning out, on schedule.

Emma felt it at once, the startling deceleration as the boosters consumed the last of the fuel. Then a brilliant flash of light in the window made her squint as the SRBs exploded away from the tank.

The roar of launch fell ominously silent, the violent shudder calming to a smooth, almost tranquil ride. In the abrupt calm, she was aware of her own pulse accelerating, her heart thudding like a fist against her chest restraint.

‘Control, this is Endeavour,’ said Kittredge, still unnaturally calm. ‘We have SRB sep.’

‘Roger, we see it.’

‘Initiating abort.’ Kittredge depressed the Abort push button, the rotary switch already positioned at the RTLS option.

Over her comm unit, Emma heard Jill Hewitt call out, ‘Emma, let’s hear the checklist!’

‘I’ve got it.’ Emma began to read aloud, and the sound of her own voice was as startlingly calm as Kittredge’s and Hewitt’s. Anyone listening to their dialogue would never have guessed they faced catastrophe. They had assumed machine mode, their panic suppressed, every action guided by rote memory and training. Their onboard computers would automatically set their return course. They were continuing downrange, still climbing to four hundred thousand feet as they dissipated fuel.

Now she felt the dizzying spin as the orbiter began its pitch-around maneuver, rolling tail over nose. The horizon, which had been upside down, suddenly righted itself as they turned back toward Kennedy, almost four hundred miles away.

‘Endeavour, this is Control. Go for main engine cutoff.’

‘Roger,’ responded Kittredge. ‘MECO now.’

On the instrument panel, the three engine status indicators suddenly flashed red. He had shut off the main engines, and in twenty seconds, the external fuel tank would drop away into the sea.

Altitude dropping fast, thought Emma. But we’re headed for home.

She gave a start. A warning buzzed, and new panel lights flashed on the console.

‘Control, we’ve lost computer number three!’ cried Hewitt. ‘We have lost a nav-state vector! Repeat, we’ve lost a nav-state vector!’

‘It could be an inertial-measurement malf,’ said Andy Mercer, the other mission specialist seated beside Emma. ‘Take it off-line.’

‘No! It might be a broken data bus!’ cut in Emma. ‘I say we engage the backup.’

‘Agreed,’ snapped Kittredge.

‘Going to backup,’ said Hewitt. She switched to computer number five.

The vector reappeared. Everyone heaved a sigh of relief.

The burst of explosive charges signaled the separation of the empty fuel tank. They couldn’t see it fall away into the sea, but they knew another crisis point had just passed. The orbiter was flying free now, a fat and awkward bird gliding homeward.

Hewitt barked, ‘Shit! We’ve lost an APU!’

Emma’s chin jerked up as a new buzzer sounded. An auxiliary power unit was out. Then another alarm screamed, and her gaze flew in panic to the consoles. A multitude of amber warning lights were flashing. On the video screens, all the data had vanished. Instead there were only ominous black and white stripes. A catastrophic computer failure. They were flying without navigation data. Without flap control.

‘Andy and I are on the APU malf!’ yelled Emma.

‘Reengage backup!’

Hewitt flicked the switch and cursed. ‘I’m getting no joy, guys. Nothing’s happening—’

‘Do it again!’

‘Still not reengaging.’

‘She’s banking!’ cried Emma, and felt her stomach lurch sideways.

Kittredge wrestled with the joystick, but they had already rolled too far starboard. The horizon reeled to vertical and flipped upside down. Emma’s stomach lurched again as they spun right side up. The next rotation came faster, the horizon twisting in a sickening whirl of sky and sea and sky.

A death spiral.

She heard Hewitt groan, heard Kittredge say, with flat resignation, ‘I’ve lost her.’

Then the fatal spin accelerated, plunging to an abrupt and shocking end.

There was only silence.

An amused voice said over their comm units, ‘Sorry, guys. You didn’t make it that time.’

Emma yanked off her headset. ‘That wasn’t fair, Hazel!’

Jill Hewitt chimed in with a protesting, ‘Hey, you meant to kill us. There was no way to save it.’

Emma was the first crew member to scramble out of the shuttle flight simulator. With the others right behind her, she marched into the windowless control room, where their three instructors sat at the row of consoles.

Team Leader Hazel Barra, wearing a mischievous smile, swiveled around to face Commander Kittredge’s irate crew of four. Though Hazel looked like a buxom earth mother with her gloriously frizzy brown hair, she was, in truth, a ruthless gameplayer who ran her flight crews through the most difficult of simulations and seemed to count it as a victory whenever the crew failed to survive. Hazel was well aware of the fact that every launch could end in disaster, and she wanted her astronauts equipped with the skills to survive. Losing one of her teams was a nightmare she hoped never to face.

‘That sim really was below the belt, Hazel,’ complained Kittredge.

‘Hey, you guys keep surviving. We have to knock down your cockiness a notch.’

‘Come on,’ said Andy. ‘Two engines down on liftoff? A broken data bus? An APU out? And then you throw in a failed number five computer? How many malfs and nits is that? It’s not realistic.’

Patrick, one of the other instructors, swiveled around with a grin. ‘You guys didn’t even notice the other stuff we did.’

‘What else was there?’

‘I threw in a nit on your oxygen tank sensor. None of you saw the change in the pressure gauge, did you?’

Kittredge gave a laugh. ‘When did we have time? We were juggling a dozen other malfunctions.’

Hazel raised a stout arm in a call for a truce. ‘Okay, guys. Maybe we did overdo it. Frankly, we were surprised you got as far as you did with the RTLS abort. We wanted to throw in another wrench, to make it more interesting.’

‘You threw in the whole damn toolbox,’ snorted Hewitt.

‘The truth is,’ said Patrick, ‘you guys are a little cocky.’

‘The word is confident,’ said Emma.

‘Which is good,’ Hazel admitted. ‘It’s good to be confident. You showed great teamwork at the integrated sim last week. Even Gordon Obie said he was impressed.’

‘The Sphinx said that?’ Kittredge’s eyebrow lifted in surprise. Gordon Obie was the director of Flight Crew Operations, a man so bafflingly silent and aloof that no one at JSC really knew him. He would sit through entire mission management meetings without uttering a single word, yet no one doubted he was mentally recording every detail. Among the astronauts, Obie was viewed with both awe and more than a little fear. With his power over final flight assignments, he could make or break your career. The fact that he had praised Kittredge’s team was good news indeed.

In her next breath, though, Hazel kicked the pedestal out from under them. ‘However,’ she said, ‘Obie is also concerned that you guys are too lighthearted about this. That it’s still a game to you.’

‘What does Obie expect us to do?’ said Hewitt. ‘Obsess over the ten thousand ways we could crash and burn?’

‘Disaster is not theoretical.’

Hazel’s statement, so quietly spoken, made them fall momentarily silent. Since Challenger, every member of the astronaut corps was fully aware that it was only a matter of time before there was another major mishap. Human beings sitting atop rockets primed to explode with five million pounds of thrust can’t afford to be sanguine about the hazards of their profession. Yet they seldom spoke about dying in space; to talk about it was to admit its possibility, to acknowledge that the next Challenger might carry one’s name on the crew roster.

Hazel realized she’d thrown a damper on their high spirits. It was not a good way to end a training session, and now she backpedaled on her earlier criticism.

‘I’m only saying this because you guys are already so well integrated. I have to work hard to trip you up. You’ve got three months till launch, and you’re already in good shape. But I want you in even better shape.’

‘In other words, guys,’ said Patrick from his console. ‘Not so cocky.’

Bob Kittredge dipped his head in mock humility. ‘We’ll go home now and put on the hair shirts.’

‘Overconfidence is dangerous,’ said Hazel. She rose from the chair and stood up to face Kittredge. A veteran of three shuttle flights, Kittredge was half a head taller, and he had the confident bearing of a naval pilot, which he had once been. Hazel was not intimidated by Kittredge, or by any of her astronauts. Whether they were rocket scientists or military heroes, they inspired in her the same maternal concern: the wish that they make it back from their missions alive.

She said, ‘You’re so good at command, Bob, you’ve lulled your crew into thinking it’s easy.’

‘No, they make it look easy. Because they’re good.’

‘We’ll see. The integrated sim’s on for Tuesday, with Hawley and Higuchi aboard. We’ll be pulling some new tricks out of the hat.’

Kittredge grinned. ‘Okay, try to kill us. But be fair about it.’

‘Fate seldom plays fair,’ Hazel said solemnly. ‘Don’t expect me to.’

Emma and Bob Kittredge sat in a booth in the Fly By Night saloon, sipping beers as they dissected the day’s simulations. It was a ritual they’d established eleven months ago, early in their team building, when the four of them had first come together as the crew for shuttle flight 162. Every Friday evening, they would meet in the Fly By Night, located just up NASA Road 1 from Johnson Space Center, and review the progress of their training. What they’d done right, what still needed improvement. Kittredge, who’d personally selected each member of his crew, had started the ritual. Though they were already working together more than sixty hours a week, he never seemed eager to go home. Emma had thought it was because the recently divorced Kittredge now lived alone and dreaded returning to his empty house. But as she’d come to know him better, she realized these meetings were simply his way of prolonging the adrenaline high of his job. Kittredge lived to fly. For sheer entertainment he read the painfully dry shuttle manuals. He spent every free moment at the controls of one of NASA’s T-38s. It was almost as if he resented the force of gravity binding his feet to the earth.

He couldn’t understand why the rest of his crew might want to go home at the end of the day, and tonight he seemed a little melancholy that just the two of them were sitting at their usual table in the Fly By Night. Jill Hewitt was at her nephew’s piano recital, and Andy Mercer was home celebrating his tenth wedding anniversary. Only Emma and Kittredge had shown up at the appointed hour, and now that they’d finished hashing over the week’s sims, there was a long silence between them. The conversation had run out of shop talk and therefore out of steam.

‘I’m taking one of the T-38s up to White Sands tomorrow,’ he said. ‘You want to join me?’

‘Can’t. I have an appointment with my lawyer.’

‘So you and Jack are forging ahead with it?’

She sighed. ‘The momentum’s established. Jack has his lawyer, and I have mine. This divorce has turned into a runaway train.’

‘It sounds like you’re having second thoughts.’

Firmly she set down her beer. ‘I don’t have any second thoughts.’

‘Then why’re you still wearing his ring?’

She looked down at the gold wedding band. With sudden ferocity she tried to yank it off, but found it wouldn’t budge. After seven years on her finger, the ring seemed to have molded itself to her flesh, refusing to be dislodged. She cursed and gave another tug, this time pulling so hard the ring scraped off skin as it slid over her knuckle. She set the ring down on the table. ‘There. A free woman.’

Kittredge laughed. ‘You two have been dragging out your divorce longer than I was married. What are you two still haggling over, anyway?’