Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Never Say Die / Presumed Guilty: Never Say Die / Presumed Guilty»

Thrilling praise for

‘Tess Gerritsen is an automatic must-read in my house.

If you’ve never read Gerritsen, figure in the price

of electricity when you buy your first novel by her,

’cause, baby, you are going to be up all night. She is

better than Palmer, better than Cook… Yes, even

better than Crichton.’

—Stephen King

‘[Gerritsen] has an imagination…so dark and

frightening that she makes Edgar Allan Poe…

seem like goody-two-shoes’

—Chicago Tribune

‘Superior to Patricia Cornwell and

as good as James Patterson…’

—Bookseller

‘It’s scary just how good Tess Gerritsen is…’

—Harlan Coben

‘Gerritsen has enough in the locker to seriously worry

Michael Connelly, Harlan Coben and even the great

Denis Lehane. Brilliant.’

—Crimetime

‘Gerritsen is tops in her genre.’

—USA TODAY

‘Tess Gerritsen writes some of the smartest, most

compelling thrillers around.’

—Bookreporter

Also available by Tess Gerritsen

IN THEIR FOOTSTEPS

UNDER THE KNIFE

CALL AFTER MIDNIGHT

NEVER SAY DIE

STOLEN

WHISTLEBLOWER

PRESUMED GUILTY

MURDER & MAYHEM COLLECTION

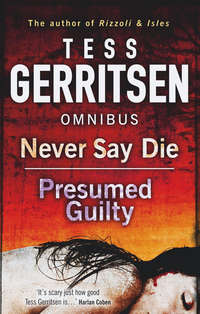

Omnibus

Never Say Die

Presumed

Guilty

Tess

Gerritsen

Never Say Die

To Adam and Joshua, the little rascals

Prologue

1970

Laos–North Vietnam border

THIRTY MILES OUT of Muong Sam, they saw the first tracers slash the sky.

Pilot William “Wild Bill” Maitland felt the DeHavilland Twin Otter buck like a filly as they took a hit somewhere back in the fuselage. He pulled into a climb, instinctively opting for the safety of altitude. As the misty mountains dropped away beneath them, a new round of tracers streaked past, splattering the cockpit with flak.

“Damn it, Kozy. You’re bad luck,” Maitland muttered to his copilot. “Seems like every time we go up together, I taste lead.”

Kozlowski went right on chomping his wad of bubble gum. “What’s to worry?” he drawled, nodding at the shattered windshield. “Missed ya by at least two inches.”

“Try one inch.”

“Big difference.”

“One extra inch can make a hell of a lot of difference.”

Kozy laughed and looked out the window. “Yeah, that’s what my wife tells me.”

The door to the cockpit swung open. Valdez, the cargo kicker, his shoulders bulky with a parachute pack, stuck his head in. “What the hell’s goin’ on any—” He froze as another tracer spiraled past.

“Got us some mighty big mosquitoes out there,” Kozlowski said and blew a huge pink bubble.

“What was that?” asked Valdez. “AK-47?”

“Looks more like .57-millimeter,” said Maitland.

“They didn’t say nothin’ about no .57s. What kind of briefing did we get, anyway?”

Kozlowski shrugged. “Only the best your tax dollars can buy.”

“How’s our ‘cargo’ holding up?” Maitland asked. “Pants still dry?”

Valdez leaned forward and confided, “Man, we got us one weird passenger back there.”

“So what’s new?” Kozlowski said.

“I mean, this one’s really strange. Got flak flyin’ all ’round and he doesn’t bat an eye. Just sits there like he’s floatin’ on some lily pond. You should see the medallion he’s got ’round his neck. Gotta weigh at least a kilo.”

“Come on,” said Kozlowski.

“I’m tellin’ you, Kozy, he’s got a kilo of gold hangin’ around that fat little neck of his. Who is he?”

“Some Lao VIP,” said Maitland.

“That all they told you?”

“I’m just the delivery boy. Don’t need to know any more than that.” Maitland leveled the DeHavilland off at eight thousand feet. Glancing back through the open cockpit doorway, he caught sight of their lone passenger sitting placidly among the jumble of supply crates. In the dim cabin, the Lao’s face gleamed like burnished mahogany. His eyes were closed, and his lips were moving silently. In prayer? wondered Maitland. Yes, the man was definitely one of their more interesting cargoes.

Not that Maitland hadn’t carried strange passengers before. In his ten years with Air America, he’d transported German shepherds and generals, gibbons and girlfriends. And he’d fly them anywhere they had to go. If hell had a landing strip, he liked to say, he’d take them there—as long as they had a ticket. Anything, anytime, anywhere, was the rule at Air America.

“Song Ma River,” said Kozlowski, glancing down through the fingers of mist at the lush jungle floor. “Lot of cover. If they got any more .57s in place, we’re gonna have us a hard landing.”

“Gonna be a hard landing anyhow,” said Maitland, taking stock of the velvety green ridges on either side of them. The valley was narrow; he’d have to swoop in fast and low. It was a hellishly short landing strip, nothing but a pin scratch in the jungle, and there was always the chance of an unreported gun emplacement. But the orders were to drop the Lao VIP, whoever he was, just inside North Viet-namese territory. No return pickup had been scheduled; it sounded to Maitland like a one-way trip to oblivion.

“Heading down in a minute,” he called over his shoulder to Valdez. “Get the passenger ready. He’s gonna have to hit the ground running.”

“He says that crate goes with him.”

“What? I didn’t hear anything about a crate.”

“They loaded it on at the last minute. Right after we took on supplies for Nam Tha. Pretty heavy sucker. I might need some help.”

Kozlowski resignedly unbuckled his seatbelt. “Okay,” he said with a sigh. “But remember, I don’t get paid for kickin’ crates.”

Maitland laughed. “What the hell do you get paid for?”

“Oh, lots of things,” Kozlowski said lazily, ducking past Valdez and through the cockpit door. “Eatin’. Sleepin’. Tellin’ dirty jokes—”

His last words were cut off by a deafening blast that shattered Maitland’s eardrums. The explosion sent Kozlowski—or what was left of Kozlowski—flying backward into the cockpit. Blood spattered the control panel, obscuring the altimeter dial. But Maitland didn’t need the altimeter to tell him they were going down fast.

“Kozy!” screamed Valdez, staring down at the remains of the copilot. “Kozy!”

His words were almost lost in the howling maelstrom of wind. The DeHavilland shuddered, a wounded bird fighting to stay aloft. Maitland, wrestling with the controls, knew immediately that he’d lost hydraulics. The best he could hope for was a belly flop on the jungle canopy.

He glanced back to survey the damage and saw, through a swirling cloud of debris, the bloodied body of the Lao passenger, thrown against the crates. He also saw sunlight shining through oddly twisted steel, glimpsed blue sky and clouds where the cargo door should have been. What the hell? Had the blast come from inside the plane?

He screamed to Valdez, “Bail out!”

The cargo kicker didn’t respond; he was still staring in horror at Kozlowski.

Maitland gave him a shove. “Get the hell out of here!”

Valdez at last reacted. He stumbled out of the cockpit and into the morass of broken crates and rent metal. At the gaping cargo door he paused. “Maitland?” he yelled over the wind’s shriek.

Their gazes met, and in that split second, they knew. They both knew. It was the last time they’d see each other alive.

“I’ll be out!” Maitland shouted. “Go!”

Valdez backed up a few steps. Then he launched himself out the cargo door.

Maitland didn’t glance back to see if Valdez’s parachute had opened; he had other things to worry about.

The plane was sputtering into a dive.

Even as he reached for his harness release, he knew his luck had run out. He had neither the time nor the altitude to struggle into his parachute. He’d never believed in wearing one anyway. Strapping it on was like admitting you didn’t trust your skill as a pilot, and Maitland knew—everyone knew—that he was the best.

Calmly he refastened his harness and grasped the controls. Through the shattered cockpit window he watched the jungle floor, lush and green and heartwrenchingly beautiful, swoop up to meet him. Somehow he’d always known it would end this way: the wind whistling through his crippled plane, the ground rushing toward him, his hands gripping the controls. This time he wouldn’t be walking away…

It was startling, this sudden recognition of his own mortality. An astonishing thought. I’m going to die.

And astonishment was exactly what he felt as the DeHavilland sliced into the treetops.

Vientiane, Laos

AT 1900 HOURS THE REPORT came in that Air America Flight 5078 had vanished.

In the Operations Room of the U.S. Army Liaison, Colonel Joseph Kistner and his colleagues from Central and Defense Intelligence greeted the news with shocked silence. Had their operation, so carefully conceived, so vital to U.S. interests, met with disaster?

Colonel Kistner immediately demanded confirmation.

The command at Air America provided the details. Flight 5078, due in Nam Tha at 1500 hours, had never arrived. A search of the presumed flight path—carried on until darkness intervened—had revealed no sign of wreckage. But flak had been reported heavy near the border, and .57-millimeter gun emplacements were noted just out of Muong Sam. To make things worse, the terrain was mountainous, the weather unpredictable and the number of alternative nonhostile landing strips limited.

It was a reasonable assumption that Flight 5078 had been shot down.

Grim acceptance settled on the faces of the men gathered around the table. Their brightest hope had just perished aboard a doomed plane. They looked at Kistner and awaited his decision.

“Resume the search at daybreak,” he said.

“That’d be throwing away live men after dead,” said the CIA officer. “Come on, gentlemen. We all know that crew’s gone.”

Cold-blooded bastard, thought Kistner. But as always, he was right. The colonel gathered together his papers and rose to his feet. “It’s not the men we’re searching for,” he said. “It’s the wreckage. I want it located.”

“And then what?”

Kistner snapped his briefcase shut. “We melt it.”

The CIA officer nodded in agreement. No one argued the point. The operation had met with disaster. There was nothing more to be done.

Except destroy the evidence.

Chapter One

Present

Bangkok, Thailand

GENERAL JOE KISTNER did not sweat, a fact that utterly amazed Willy Jane Maitland, since she herself seemed to be sweating through her sensible cotton underwear, through her sleeveless chambray blouse, all the way through her wrinkled twill skirt. Kistner looked like the sort of man who ought to be sweating rivers in this heat. He had a fiercely ruddy complexion, bulldog jowls, a nose marbled with spidery red veins, and a neck so thick, it strained to burst free of his crisp military collar. Every inch the blunt, straight-talking, tough old soldier, she thought. Except for the eyes. They’re uneasy. Evasive.

Those eyes, a pale, chilling blue, were now gazing across the veranda. In the distance the lush Thai hills seemed to steam in the afternoon heat. “You’re on a fool’s errand, Miss Maitland,” he said. “It’s been twenty years. Surely you agree your father is dead.”

“My mother’s never accepted it. She needs a body to bury, General.”

Kistner sighed. “Of course. The wives. It’s always the wives. There were so many widows, one tends to forget—”

“She hasn’t forgotten.”

“I’m not sure what I can tell you. What I ought to tell you.” He turned to her, his pale eyes targeting her face. “And really, Miss Maitland, what purpose does this serve? Except to satisfy your curiosity?”

That irritated her. It made her mission seem trivial, and there were few things Willy resented more than being made to feel insignificant. Especially by a puffed up, flat-topped warmonger. Rank didn’t impress her, certainly not after all the military stuffed shirts she’d met in the past few months. They’d all expressed their sympathy, told her they couldn’t help her and proceeded to brush off her questions. But Willy wasn’t a woman to be stonewalled. She’d chip away at their silence until they’d either answer her or kick her out.

Lately, it seemed, she’d been kicked out of quite a few offices.

“This matter is for the Casualty Resolution Committee,” said Kistner. “They’re the proper channel to go—”

“They say they can’t help me.”

“Neither can I.”

“We both know you can.”

There was a pause. Softly, he asked, “Do we?”

She leaned forward, intent on claiming the advantage. “I’ve done my homework, General. I’ve written letters, talked to dozens of people—everyone who had anything to do with that last mission. And whenever I mention Laos or Air America or Flight 5078, your name keeps popping up.”

He gave her a faint smile. “How nice to be remembered.”

“I heard you were the military attaché in Vientiane. That your office commissioned my father’s last flight. And that you personally ordered that final mission.”

“Where did you hear that rumor?”

“My contacts at Air America. Dad’s old buddies. I’d call them a reliable source.”

Kistner didn’t respond at first. He was studying her as carefully as he would a battle plan. “I may have issued such an order,” he conceded.

“Meaning you don’t remember?”

“Meaning it’s something I’m not at liberty to discuss. This is classified information. What happened in Laos is an extremely sensitive topic.”

“We’re not discussing military secrets here. The war’s been over for fifteen years!”

Kistner fell silent, surprised by her vehemence. Given her unassuming size, it was especially startling. Obviously Willy Maitland, who stood five-two, tops, in her bare feet, could be as scrappy as any six-foot marine, and she wasn’t afraid to fight. From the minute she’d walked onto his veranda, her shoulders squared, her jaw angled stubbornly, he’d known this was not a woman to be ignored. She reminded him of that old Eisenhower chestnut, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight but the size of the fight in the dog.” Three wars, fought in Japan, Korea and Nam, had taught Kistner never to underestimate the enemy.

He wasn’t about to underestimate Wild Bill Maitland’s daughter, either.

He shifted his gaze across the wide veranda to the brilliant green mountains. In a wrought-iron birdcage, a macaw screeched out a defiant protest.

At last Kistner began to speak. “Flight 5078 took off from Vientiane with a crew of three—your father, a cargo kicker and a copilot. Sometime during the flight, they diverted across North Vietnamese territory, where we assume they were shot down by enemy fire. Only the cargo kicker, Luis Valdez, managed to bail out. He was immediately captured by the North Vietnamese. Your father was never found.”

“That doesn’t mean he’s dead. Valdez survived—”

“I’d hardly call the man’s outcome ‘survival.’”

They paused, a momentary silence for the man who’d endured five years as a POW, only to be shattered by his return to civilization. Luis Valdez had returned home on a Saturday and shot himself on Sunday.

“You left something out, General,” said Willy. “I’ve heard there was a passenger…”

“Oh. Yes,” said Kistner, not missing a beat. “I’d forgotten.”

“Who was he?”

Kistner shrugged. “A Lao. His name’s not important.”

“Was he with Intelligence?”

“That information, Miss Maitland, is classified.” He looked away, a gesture that told her the subject of the Lao was definitely off-limits. “After the plane went down,” he continued, “we mounted a search. But the ground fire was hot. And it became clear that if anyone had survived, they’d be in enemy hands.”

“So you left them there.”

“We don’t believe in throwing lives away, Miss Maitland. That’s what a rescue operation would’ve been. Throwing live men after dead.”

Yes, she could see his reasoning. He was a military tactician, not given to sentimentality. Even now, he sat ramrod straight in his chair, his eyes calmly surveying the verdant hills surrounding his villa, as though eternally in search of some enemy.

“We never found the crash site,” he continued. “But that jungle could swallow up anything. All that mist and smoke hanging over the valleys. The trees so thick, the ground never sees the light of day. But you’ll get a feeling for it yourself soon enough. When are you leaving for Saigon?”

“Tomorrow morning.”

“And the Vietnamese have agreed to discuss this matter?”

“I didn’t tell them my reason for coming. I was afraid I might not get the visa.”

“A wise move. They aren’t fond of controversy. What did you tell them?”

“That I’m a plain old tourist.” She shook her head and laughed. “I’m on the deluxe private tour. Six cities in two weeks.”

“That’s what one has to do in Asia. You don’t confront the issues. You dance around them.” He looked at his watch, a clear signal that the interview had come to an end.

They rose to their feet. As they shook hands, she felt him give her one last, appraising look. His grip was brisk and matter-of-fact, exactly what she expected from an old war dog.

“Good luck, Miss Maitland,” he said with a nod of dismissal. “I hope you find what you’re looking for.”

He turned to look off at the mountains. That’s when she noticed for the first time that tiny beads of sweat were glistening like diamonds on his forehead.

GENERAL KISTNER WATCHED as the woman, escorted by a servant, walked back toward the house. He was uneasy. He remembered Wild Bill Maitland only too clearly, and the daughter was very much like him. There would be trouble.

He went to the tea table and rang a silver bell. The tinkling drifted across the expanse of veranda, and seconds later, Kistner’s secretary appeared.

“Has Mr. Barnard arrived?” Kistner asked.

“He has been waiting for half an hour,” the man replied.

“And Ms. Maitland’s driver?”

“I sent him away, as you directed.”

“Good.” Kistner nodded. “Good.”

“Shall I bring Mr. Barnard in to see you?”

“No. Tell him I’m canceling my appointments. Tomorrow’s, as well.”

The secretary frowned. “He will be quite annoyed.”

“Yes, I imagine he will be,” said Kistner as he turned and headed toward his office. “But that’s his problem.”

A THAI SERVANT IN A CRISP white jacket escorted Willy through an echoing, cathedral-like hall to the reception room. There he stopped and gave her a politely questioning look. “You wish me to call a car?” he asked.

“No, thank you. My driver will take me back.”

The servant looked puzzled. “But your driver left some time ago.”

“He couldn’t have!” She glanced out the window in annoyance. “He was supposed to wait for—”

“Perhaps he is parked in the shade beyond the trees. I will go and look.”

Through the French windows, Willy watched as the servant skipped gracefully down the steps to the road. The estate was vast and lushly planted; a car could very well be hidden in that jungle. Just beyond the driveway, a gardener clipped a hedge of jasmine. A neatly graveled path traced a route across the lawn to a tree-shaded garden of flowers and stone benches. And in the far distance, a fairy blue haze seemed to hang over the city of Bangkok.

The sound of a masculine throat being cleared caught her attention. She turned and for the first time noticed the man standing in a far corner of the reception room. He cocked his head in a casual acknowledgment of her presence. She caught a glimpse of a crooked grin, a stray lock of brown hair drooping over a tanned forehead. Then he turned his attention back to the antique tapestry on the wall.

Strange. He didn’t look like the sort of man who’d be interested in moth-eaten embroidery. A patch of sweat had soaked through the back of his khaki shirt, and his sleeves were shoved up carelessly to his elbows. His trousers looked as if they’d been slept in for a week. A briefcase, stamped U.S. Army ID Lab, sat on the floor beside him, but he didn’t strike her as the military type. There was certainly nothing disciplined about his posture. He’d seem more at home slouching at a bar somewhere instead of cooling his heels in General Kistner’s marble reception room.

“Miss Maitland?”

The servant was back, shaking his head apologetically. “There must have been a misunderstanding. The gardener says your driver returned to the city.”

“Oh, no.” She looked out the window in frustration. “How do I get back to Bangkok?”

“Perhaps General Kistner’s driver can take you back? He has gone up the road to make a delivery, but he should return very soon. If you wish, you can see the garden in the meantime.”

“Yes. Yes, I suppose that’d be nice.”

The servant, smiling proudly, opened the door. “It is a very famous garden. General Kistner is known for his collection of dendrobiums. You will find them at the end of the path, near the carp pond.”

She stepped out into the steam bath of late afternoon and started down the gravel path. Except for the clack-clack of the gardener’s hedge clippers, the day was absolutely still. She headed toward a stand of trees. But halfway across the lawn she suddenly stopped and looked back at the house.

At first all she saw was sunlight glaring off the marble facade. Then she focused on the first floor and saw the figure of a man standing at one of the windows. The servant, perhaps?

Turning, she continued along the path. But every step of the way, she was acutely aware that someone was watching her.

GUY BARNARD STOOD AT THE French windows and observed the woman cross the lawn to the garden. He liked the way the sunlight seemed to dance in her clipped, honeycolored hair. He also liked the way she moved, the coltish swing of her walk. Methodically, his gaze slid down, over the sleeveless blouse and the skirt with its regrettably sensible hemline, taking in the essentials. Trim waist. Sweet hips. Nice calves. Nice ankles. Nice…

He reluctantly cut off that disturbing train of thought. This was not a good time to be distracted. Still, he couldn’t help one last appreciative glance at the diminutive figure. Okay, so she was a touch on the scrawny side. But she had great legs. Definitely great legs.

Footsteps clipped across the marble floor. Guy turned and saw Kistner’s secretary, an unsmiling Thai with a beardless face.

“Mr. Barnard?” said the secretary. “Our apologies for the delay. But an urgent matter has come up.”

“Will he see me now?”

The secretary shifted uneasily. “I am afraid—”

“I’ve been waiting since three.”

“Yes, I understand. But there is a problem. It seems General Kistner cannot meet with you as planned.”

“May I remind you that I didn’t request this meeting. General Kistner did.”

“Yes, but—”

“I’ve taken time out of my busy schedule—” he took the liberty of exaggeration “—to drive all the way out here, and—”

“I understand, but—”

“At least tell me why he insisted on this appointment.”

“You will have to ask him.”

Guy, who up till now had kept his irritation in check, drew himself up straight. Though he wasn’t a particularly tall man, he stood a full head taller than the secretary. “Is this how the general normally conducts business?”

The secretary merely shrugged. “I am sorry, Mr. Barnard. The change was entirely unexpected…” His gaze shifted momentarily and focused on something beyond the French windows.

Guy followed the man’s gaze. Through the glass, he saw what the man was looking at: the woman with the honeycolored hair.

The secretary shuffled his feet, a signal that he had other duties to attend to. “I assure you, Mr. Barnard,” he said, “if you call in a few days, we will arrange another appointment.”

Guy snatched up his briefcase and headed for the door. “In a few days,” he said, “I’ll be in Saigon.”

A whole afternoon wasted, he thought in disgust as he walked down the front steps. He swore again as he reached the empty driveway. His car was parked a good hundred yards away, in the shade of a poinciana tree. The driver was nowhere to be seen. Knowing Puapong, the man was probably off flirting with the gardener’s daughter.

Resignedly Guy trudged toward the car. The sun was like a broiler, and waves of heat radiated from the gravel road. Halfway to the car, he happened to glance at the garden, and he spotted the honey-haired woman, sitting on a stone bench. She looked dejected. No wonder; it was a long drive back to town, and Lord only knew when her ride would turn up.

What the hell, he thought, starting toward her. He could use some company.

She seemed to be deep in thought; she didn’t look up until he was standing right beside her.

“Hi there,” he said.

She squinted up at him. “Hello.” Her greeting was neutral, neither friendly nor unfriendly.

“Did I hear you needed a lift back to town?”

“I have one, thank you.”

“It could be a long wait. And I’m heading there anyway.” She didn’t respond, so he added, “It’s really no trouble.”

She gave him a speculative look. She had silver-gray eyes, direct, unflinching; they seemed to stare right through him. No shrinking violet, this one. Glancing back at the house, she said, “Kistner’s driver was going to take me…”

“I’m here. He isn’t.”

Again she gave him that look, a silent third degree. She must have decided he was okay, because she finally rose to her feet. “Thanks. I’d appreciate it.”

Together they walked the graveled road to his car. As they approached, Guy noticed a back door was wide open and a pair of dirty brown feet poked out. His driver was sprawled across the seat like a corpse.

The woman halted, staring at the lifeless form. “Oh, my God. He’s not—”

A blissful snore rumbled from the car.

“He’s not,” said Guy. “Hey. Puapong!” He banged on the car roof.

The man’s answering rumble could have drowned out thunder.

“Hello, Sleeping Beauty!” Guy banged the car again. “You gonna wake up, or do I have to kiss you first?”

“What? What?” groaned a voice. Puapong stirred and opened one bloodshot eye. “Hey, boss. You back so soon?”

“Have a nice nap?” Guy asked pleasantly.

“Not bad.”

Guy graciously gestured for Puapong to vacate the back seat. “Look, I hate to be a pest, but do you mind? I’ve offered this lady a ride.”

Puapong crawled out, stumbled around sleepily to the driver’s seat and sank behind the wheel. He shook his head a few times, then fished around on the floor for the car keys.

The woman was looking more and more dubious. “Are you sure he can drive?” she muttered under her breath.

“This man,” said Guy, “has the reflexes of a cat. When he’s sober.”

“Is he sober?”

“Puapong! Are you sober?”

With injured pride, the driver asked, “Don’t I look sober?”

“There’s your answer,” said Guy.

The woman sighed. “That makes me feel so much better.” She glanced back longingly at the house. The Thai servant had appeared on the steps and was waving goodbye.

Guy motioned for the woman to climb in. “It’s a long drive back to town.”

She was silent as they drove down the winding mountain road. Though they both sat in the back seat, two feet apart at the most, she seemed a million miles away. She kept her gaze focused on the scenery.

“You were in with the general quite a while,” he noted.

She nodded. “I had a lot of questions.”

“You a reporter?”

“What?” She looked at him. “Oh, no. It was just…some old family business.”

He waited for her to elaborate, but she turned back to the window.

“Must’ve been some pretty important family business,” he said.

“Why do you say that?”

“Right after you left, he canceled all his appointments. Mine included.”

“You didn’t get in to see him?”

“Never got past the secretary. And Kistner’s the one who asked to see me.”

She frowned for a moment, obviously puzzled. Then she shrugged. “I’m sure I had nothing to do with it.”

And I’m just as sure you did, he thought in sudden irritation. Lord, why was the woman making him so antsy? She was sitting perfectly still, but he got the distinct feeling a hurricane was churning in that pretty head. He’d decided that she was pretty after all, in a no-nonsense sort of way. She was smart not to use any makeup; it would only cheapen that girl-next-door face. He’d never before had any interest in the girl-next-door type. Maybe the girl down the street or across the tracks. But this one was different. She had eyes the color of smoke, a square jaw and a little boxer’s nose, lightly dusted with freckles. She also had a mouth that, given the right situation, could be quite kissable.

Automatically he asked, “So how long will you be in Bangkok?”

“I’ve been here two days already. I’m leaving tomorrow.”

Damn, he thought.

“For Saigon.”

His chin snapped up in surprise. “Saigon?”

“Or Ho Chi Minh City. Whatever they call it these days.”

“Now that’s a coincidence,” he said softly.

“What is?”

“In two days, I’m leaving for Saigon.”

“Are you?” She glanced at the briefcase, stenciled with U.S. Army ID Lab, lying on the seat. “Government affairs?”

He nodded. “What about you?”

She looked straight ahead. “Family business.”

“Right,” he said, wondering what the hell business her family was in. “You ever been to Saigon?”

“Once. But I was only ten years old.”

“Dad in the service?”

“Sort of.” Her gaze stayed fixed on some faraway point ahead. “I don’t remember too much of the city. Lot of dust and heat and cars. One big traffic jam. And the beautiful women…”

“It’s changed a lot since then. Most of the cars are gone.”

“And the beautiful women?”

He laughed. “Oh, they’re still around. Along with the heat and dust. But everything else has changed.” He was silent a moment. Then, almost as an afterthought, he added, “If you get stuck, I might be able to show you around.”