Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

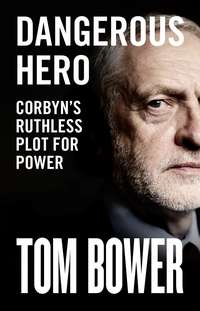

Kitabı oku: «Dangerous Hero»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Tom Bower 2019

Cover image © Getty Images

Tom Bower asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publishers have made every effort to credit the copyright holders of the material used in this book. If we have incorrectly credited your copyright material please contact us for correction in future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008299576

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008299590

Version: 2019-03-18

Dedication

To Veronica

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Islington, Late 1996

1 Rebel With a Cause

2 The First Rung

3 The Deadly Duo

4 The Other Comrade

5 Four Legs Good, Two Legs Bad

6 The Harmless Extremist

7 Circle of Fear

8 Lame Ducks

9 Party Games

10 The Takeover

11 The Purge

12 The Jew-Haters

13 Stuck in the Bunker

14 Squashing the Opposition

15 The Coming of St Jeremy

16 Game-Changer

17 Resurrection

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Preface

The genesis of this book started exactly fifty years ago.

At the end of January 1969, a group of Marxist and Trotskyist students at the London School of Economics led a stormy protest against the school’s director, an authoritarian from Southern Rhodesia. He had ordered the staff to close a series of gates inside the building in Aldwych to prevent a students’ meeting in the school’s Old Theatre. In the mêlée, at about 5 p.m., a caretaker guarding the gates died from a heart attack and the students instantly started a month-long occupation, igniting similar sit-ins across Britain’s universities.

Throughout that first night of occupation, hundreds of LSE students crowded into the Old Theatre to debate the prospects of a Marxist revolution in Britain. Led by American graduates from Berkeley, California, where the student revolt against the Vietnam War had started five years before, and with speeches from French and German students, battle-scarred from 1968 street fights in Paris and Berlin, LSE’s Marxists and Trotskyists (there were many) told us we were the vanguard of a worldwide revolution – which would begin with the students, and the workers would follow. We believed it.

Aged twenty-three and from a conservative background, I had completed my law degree at the LSE (the country’s best law faculty at the time), and while studying for the Bar exams was employed on legal research projects at the college. Long before that dramatic night I had concluded that English law protected property rights at the expense of the rights of individuals and real democracy. Surrounded by articulate Marxists studying sociology and government, and going to lectures by Ralph Miliband and other Marxist teachers, I became attracted to their analysis of society. In that era, for anyone interested in politics that was not surprising.

In the wake of the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa in 1960 (I had marched in protest through London with my school friends against apartheid during the early years of that decade) and the anti-Vietnam protests outside the American embassy in Grosvenor Square in 1968 (along with others, I escaped with just some nasty blows from the police), I shared the horror at the dishonesty and disarray of Harold Wilson’s Labour government. Added to that, for family reasons I was influenced by events in Germany. In particular I became fascinated by Rudi Dutschke, an erudite Marxist who spoke in graphic terms in Berlin about ‘the long march through the institutions of power’ to remove the Nazis and their capitalist supporters from ruling post-war Germany. In April 1968 an attempted assassination of Dutschke illustrated the raw battle for power between good and evil raging across Europe and America. (I would meet Dutschke later in Oxford.)

Those days and nights of long debates about politics, the economy and society were decisive for many of us involved in the LSE occupation. After a month it all petered out, but that 1968 generation was marked for life. None of us attained high office in politics, industry or education. Instead, that seminal moment in Britain’s social history created cynics: men and women who were dissatisfied, curious, nonconformist and determined to expose evil in the world, of whatever type and wherever it might be found.

As ‘Tommy the Red’ (I became a students’ spokesman), that month I learned many vital lessons for the journalistic career I embarked on soon after, travelling for a week on a special train with Willy Brandt during his successful election campaign to become Germany’s chancellor. I emerged from that train with a unique insight about politicians and statecraft. Not least, that every politician is best judged by his or her closest advisers. Thereafter I spent many years producing BBC TV documentaries in Germany (about the Allied failure to prosecute Nazi war criminals and to de-Nazify post-war Germany) and across the world. Witnessing a myriad of wars, elections, corrupt politicians and shady businessmen cured me of Marxism, but not of my curiosity and innate scepticism.

LSE’s Marxist student leaders did not join the conventional world. Some died tragically young, often from suicide, while others committed their whole lives to the struggle for revolution. In researching this book I was reunited with several of them. After fifty years they had changed a good deal physically, but not in their core beliefs. Pertinently, they all genuinely sensed that their Marxist dream would finally come true, delivered by Jeremy Corbyn.

Despite being excited by that prospect, they have no illusions about Corbyn himself. None of those illustrious Marxists who have survived since the 1960s – all intelligent, well-educated, engaged and engaging – recall Corbyn as a major player over any of the four decades before his ascension as leader of the Labour Party in September 2015. On the contrary, although they did not doubt his sincerity, they were underwhelmed by his intellect. In any event, for them, winning power was all that mattered, and like many across Britain’s political spectrum, they were certain that Corbyn would be Britain’s next prime minister.

That possible outcome was the reason I wrote this book. With Corbyn having a good chance of victory, the public deserves to know more about him. Surprisingly for a politician, but not for a hard-left conspirator, he has done his best to conceal his personal life from the media – which he loathes.

My main criterion for writing previous biographies has been to identify those at the top of the greasy pole, ambitious to influence our lives but unwilling to reveal their pasts with a reasonable measure of truth. Often they have falsified their biographies to protect themselves from public criticism. Corbyn is no different. Despite his repeatedly stated commitment to improve the lives of the impoverished, fight injustice, champion equality and destroy greed, he has hidden away much about himself that is relevant to judge his character and Britain’s likely fate under the Marxist-Trotskyist government he has always promoted.

There can be no doubt about his passion to improve conditions for his constituents and the less advantaged in Britain and across the world. Frugal in his clothes and his food, he poses as the ‘good idealist’ engaged in a lifelong fight for justice and equality. In varying degrees, that aspiration is common to every politician: even tyrants don’t openly promise injustice and inequality. The difference between politicians is in their methods. Corbyn’s credo reflects his abstemious lifestyle. He disapproves of ambition and success. Equating both with greed, he strives not for equality of opportunity, but equality of poverty. In his ideal world, recognising the guilt of its shameful empire, Britain would abolish immigration controls and allow the needy to enter the country to share its wealth. For the rest, by taxation and confiscation of property, Corbyn would irreversibly transform Britain. Inevitably, there would be winners and losers; and until recently he did not conceal his contempt for his quarry. However, in his efforts to win the next general election he has starkly modified his language, and his senior colleagues have followed his lead.

Just how Corbyn became a communist has never been revealed. Before he was elected Labour’s leader he was not seen as a figure of consequence, and thereafter he did all he could to protect the mystery. Since he now offers himself as Britain’s next leader, his background story has become relevant. Is he a danger to the country? How genuine are his beliefs or his public character? Is he as benign as Labour’s spin doctors now insist?

Ever since the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1989, the number of those who advocate Marxism as a system of government has rapidly diminished. No one much under the age of forty-five is a credible witness of the oppressive dictatorships imposed by Russia on Eastern Europe. No one much under sixty can recall the industrial anarchy orchestrated by communist conspirators in Britain during the 1960s and 1970s. Only the far left looks back on that era with any nostalgia. The rest blame the widespread strikes of those years, often orchestrated by Marxists or Trotskyists, for permanent damage to Britain’s economy.

Corbyn disagrees with that assessment. For him, his election as prime minister would be the curtain-raiser to completing the unfinished business halted by Labour’s election defeat in 1979. His admirers, for whom he is a hero, agree. The older ones are resolute socialists; his younger supporters are idealists, ignorant of history. Across that spectrum, few understand the society that Corbyn and his fellow Trotskyists, including John McDonnell, Len McCluskey, Diane Abbott and Seumas Milne, intend to build.

I understand the Corbyn Utopia better than most, because I have spent my life and career among the hard left. At school and in my block of flats in north-west London, I grew up surrounded by the children of communists, and often visited their homes. In the late 1950s I began travelling to communist Czechoslovakia, and as a journalist, between 1969 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 I frequently travelled across communist East Germany to interview senior officials and study the government archives about the Nazi era. As a BBC TV reporter I spent a lot of time during the 1970s with British strikers, especially the miners led by Arthur Scargill and his fellow Marxist trade union leaders. In 1989 I began three years of work in Russia, interviewing high-ranking Soviet intelligence officers who played the spy game against the West. While filming wars in Vietnam, the Middle East and South America, I constantly encountered hard-left idealists and latterday commissars. As a result I am no stranger to the manoeuvres of Corbyn and his group to seize power, nor to their ambitions once in Downing Street.

This book, told with the help of eyewitness accounts by people who have known Corbyn throughout his life, reveals the nature of the man who, if the Conservatives successfully rip themselves apart over Europe, is set to become prime minister.

The question is whether a Labour government led by Corbyn would transform the country for the better. Has capitalism, as he argues, run its course, and would our lives be improved by socialism? If so, is Corbyn’s socialism the same brand that we have experienced under successive Labour governments since 1945, or something more radical, like a Marxist miracle? Is he a reformer or a revolutionary? And what sort of socialist is Corbyn? His supporters damn every opponent, especially Blairites, castigating each critic, even sympathetic ones, as ‘traitors’ or worse. Does that aggression, and the accusations that paint Corbyn as an entrenched anti-Semite, override his image as an authentic ‘good bloke’ blessed with everlasting politeness. As described in this book, I have found another side of the man. Would his election have a happy ending for Britain? For some, he would be a dangerous hero.

Islington, Late 1996

‘I’ve got all these debts,’ Jeremy Corbyn told his long-time friend Reg Race. ‘Can you work out why?’

‘I don’t need to be a genius to tell him what’s wrong,’ Race thought. ‘He’s in danger of bankruptcy.’ But at first he said nothing. Sitting in the Spartan living room of Corbyn’s semi-detached house in north London, Race picked up a single sheet of paper and read out the politician’s financial death warrant. Across from him sat his host and Claudia Bracchitta, Corbyn’s formidable Chilean wife. They had positioned themselves unnaturally far apart from each other.

Claudia had summoned Race as a mutual friend to solve their differences. Blending his expertise in both Marx and Mammon had won him the trust of the Corbyns. As Corbyn’s close political ally on the far left for many years, Race, a former MP, had transformed himself in recent times from a political agitator into a successful financial consultant in Britain’s health business.

The papers in front of him showed that the Corbyns owed their bank £30,000, the equivalent today of twice that figure. Several personal loans had been guaranteed by Corbyn’s income as an MP. He was also burdened by high mortgage repayments. As a last resort, the bank could threaten to recover its money by seizing his home. ‘You’ve run out of loans,’ said Race. Unchecked, within five years the debts would amount to £100,000. Corbyn’s annual salary was £43,000.

Claudia interrupted. This was entirely the result of her husband’s folly, she said. She and their three sons had little money even to buy food and clothes. ‘We can’t afford a decent life.’

The principal cause of the debts was the Red Rose Community Centre on the Seven Sisters Road in Holloway, north London. Situated in the heart of Corbyn’s constituency, the Red Rose was a bar and dance area on the ground floor of the building that fulfilled his commitment to open his party office in the constituency. Corbyn was paying its rent and some of its staff’s salaries out of his own pocket. Simultaneously, he owed a large sum to the Inland Revenue for his employees’ unpaid National Insurance and pension contributions. The financial chaos was matched by his style of management. His employees complained about being both undervalued and underpaid. Among the casualties was Liz Phillipson, his battle-scarred assistant, who had resigned rather than continue to tolerate Corbyn’s fecklessness.

‘You haven’t got enough money for what you’re doing,’ Race said bluntly. ‘You should close your office in Holloway and move to the Commons. That would cut your costs by 80 per cent.’

‘I won’t,’ replied Corbyn.

‘Oh, come on, Jeremy, you know he’s right,’ Claudia said, her voice rising. ‘Why don’t you believe him?’

Corbyn mumbled, then fell silent. His body language showed that he felt no inclination to follow Race’s recommendations. Claudia was becoming noticeably agitated. ‘It was clear a breakdown was coming,’ thought Race.

He was not surprised by the tension. Corbyn had first met his ‘utterly lovely’ wife (she had an athletic figure and a characterful face) in 1987, and soon after they decided to marry. An intellectual with a deep understanding of South America, Claudia had bonded with him at a protest meeting against Chile’s military dictatorship, addressed by Ken Livingstone. ‘She wanted to get off with me,’ Livingstone would recall, ‘but I had to go off to meet Kate, my partner, so she went for Jeremy.’ In the flush of romance and clearly infatuated, Claudia had not grasped that while her future husband’s enthusiasm for making jam or turning wood on a lathe was appealing, his lack of interest in material things meant that he ignored her need for comfort. At one stage she had planned for them and their young sons to move from Islington to leafy Kingston-upon-Thames, but was quickly disabused of the idea. ‘He has to live in his constituency,’ Keith Veness, another close political friend, informed her. ‘No one told me,’ she sighed.

Long before the onset of their financial problems, life with Corbyn had proved difficult. Tony Banks, the Labour MP for Newham North-West, witnessed just how difficult as one day he walked into Westminster’s central lobby and spotted Claudia standing by the wall, tearfully holding her children. Jeremy, she explained, had promised to meet her two hours earlier. He had not turned up. Banks took the four Corbyns to the Commons family room and went off in search. Eventually he found Corbyn in a committee room. ‘You’d better come out and look after your children,’ he suggested. Corbyn did not seem fazed for a moment. Banks was not surprised. ‘When pushed to have a day off,’ he recalled, ‘Jeremy’s idea was to take his partner to Highgate Cemetery and study the grave of Karl Marx.’

Reg Race had experienced something similar when he had invited the Corbyn family for a week’s holiday at his country home in Derbyshire. On the day, Claudia arrived with the children.

‘Where’s Jeremy?’ asked Mandy, Reg’s wife.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Claudia with sadness. ‘He just told me “I’ve got to go to a meeting,” and I haven’t seen him since.’

Over the following thirty-six hours, Claudia called several numbers searching for her husband. Two days later he turned up, explaining his absence as a necessary sacrifice for ‘the movement’. At the time, Race decided that Corbyn was absent-minded rather than neglectful. But a huge question about his attitude towards his responsibilities remained unanswered.

Shortly after, Keith Veness and his wife Val confronted the same thoughtlessness. Claudia, who had come from a middle-class family used to a certain degree of comfort, was always complaining about the shortage of money.

‘I’ve told Jeremy that he should stop being an MP and get a well-paid job,’ she confided.

‘What can Jeremy do to earn more money?’ Veness asked.

Val added, ‘The miners get much less than Jeremy.’ But Claudia, she realised, did not appreciate her husband’s hair-shirt lifestyle. She had even wanted a cleaner, but Corbyn had vetoed that. Did Claudia have bourgeois tendencies, Val wondered.

None of Corbyn’s constituents could have imagined the tension when he arrived at meetings with his family to speak about Ireland, a subject of no interest to Claudia. By contrast, he had a self-proclaimed (if questionable) passion for Arsenal Football Club. Claudia was worried about hooliganism at the team’s home matches at Highbury, while Corbyn, according to Keith Veness, regarded the game as ‘crude and awful’, and much preferred not to go. So Veness took Corbyn’s sons to matches, while their father went to political meetings.

‘Jeremy wasn’t interested in football,’ recalled Veness, contradicting Corbyn’s boast of passionate support for Arsenal. ‘Except, that was, on Cup final day.’

By late 1996 the marriage was all but over, and with nothing left in common, the two had drifted apart. To Corbyn, Claudia’s list of complaints was familiar. Ever since 1967, when he had met Andrea Davies, his first girlfriend, at the Telford Young Socialists, a succession of women had made the same observations: he never changed his ways, and he rarely thought about them. Throughout the years he wore the same shabby clothes, ate the same bland food and stuck to the same political convictions he had begun to absorb in Jamaica, where he had spent fifteen months as a teenager in the 1960s. Admirers hailed his inflexibility as proof of his uncompromising principles, and to some the purity of his other-worldliness was endearing. Detractors blamed his limited intelligence and lack of education for his failure to appreciate others. On his own account, amid a constant round of demonstrations, speeches and political manoeuvres, he claimed to avoid causing any personal insult. Further, to avoid criticising any of his partners, he would insist that politics was about ideas, not personalities.

Reg Race had helped him realise his first political dreams in the early 1970s. Ever since, Corbyn had trusted his advice, especially once his friend became the financial supremo at the Greater London Council (GLC) during Ken Livingstone’s turbulent reign in the 1980s. But as they forged a bond on the left of the Labour Party, Race had discovered Corbyn’s ignorance about the bureaucratic requirements of government, and his simple-mindedness about finances. While the committed revolutionary strove to challenge powerbrokers across the world on behalf of the oppressed, he seethed about any personal criticism in his own home. With so much to hide, he condemned any revelations about himself as abhorrent.

However, on the day in 1996 on which Race described Corbyn’s financial crisis, the focus was entirely on him. Even if a rich benefactor had volunteered to pay off all the debts (and that was improbable), he would soon have fallen behind again. He had little choice, Race told him, but to sell the family home. Claudia agreed. Reluctantly, so did Corbyn – and thereafter broke off his relations with Race. The messenger was to blame. After this experience, Race questioned Corbyn’s character and his propriety to influence the direction of the Labour movement.

In early 1999 the Corbyns’ home was sold for £365,000 (£730,000 today), and they downsized to a house in Mercers Road, a shabby street in Tufnell Park, off the Holloway Road. On the day of the move, Corbyn was told by Claudia to empty the fridge. He forgot. He also forgot to clear the garage. Late in the afternoon, while their former home’s new owner, dressed in a camelhair coat, fumed on the pavement, the garage door was opened to reveal rubbish crammed to the ceiling. Corbyn had regularly picked wood from neighbourhood skips, and also collected railway junk as he criss-crossed the country on trains. Boxes of safety lamps, metal signs, track signals and other paraphernalia had been stuffed in any old how. Late in the day, everything was finally shuttled across to the basement of Mercers Road, creating a new world of clutter.

The move brought one advantage. The building had been converted into bedsits, making the estrangement between Claudia and Corbyn easier. She and their three sons took the top floors, where she lived with a young South American dubbed ‘the toy boy’, while Corbyn, in the basement, had relationships with a series of younger women.

The couple’s estrangement was kept secret for almost two years. Late in 1999, while Corbyn was at a peace conference in The Hague, a journalist contacted Claudia and asked whether the two had separated. Instead of telling the complete truth, she explained that their twelve-year marriage had ended in 1997. She said that she had wanted their eleven-year-old son Ben to go to Queen Elizabeth’s grammar school in Barnet, but that Corbyn had stipulated that he should go instead to Holloway School, a local comprehensive notorious for achieving, for three successive years, the worst GCSE results in the country, and listed as ‘failing’ by Ofsted, the office for standards in education.

From The Hague, Corbyn confirmed Claudia’s account. Defending his ideological purity against selective schools, he implied, was more important than his son’s education – or his marriage. To avoid being branded a hypocrite, he said he preferred his son to be badly educated than to be given an unfair advantage. Labour’s Islington council, he knew, despite receiving additional government funds, had failed to improve Holloway. The school was plagued with discipline problems and classes in which up to twenty languages were spoken, the white pupils being especially disadvantaged.

In a series of interviews, Claudia reinforced the same message. ‘My children’s education is my absolute priority, and this situation left me with no alternative but to accept a place at Queen Elizabeth Boys’ School. I had to make the decision as a mother and a parent … It isn’t a story about making a choice, but about having no choice. I couldn’t send Ben to a school where I knew he wouldn’t be happy.’ To the public Corbyn appeared to have acquiesced in his wife’s wishes, but, like so many communists, he had put his political principles first, and ended the marriage: he could not live with a woman who did not accept his beliefs. The only dent to that image of ideological purity was Claudia’s revelation that Corbyn had agreed for another of their sons to spend two years at the local Montessori nursery, at £600 per term.

If that had been the last word on the subject, the notion that the marriage had broken up over Corbyn’s principles might have been plausible. He favoured, he said, France’s strict laws on the privacy of public figures’ family lives – laws which have been exploited to conceal rampant corruption among French politicians, including former presidents. But Claudia, possibly with Corbyn’s encouragement, went further. ‘He is first the politician and second the parent,’ she said. ‘He definitely felt it would have compromised his career if he had made the same choice that I did. It’s very difficult when your ideals get in the way of family life … It has been a horrendous decision.’

Sixteen years later, the whole tale was expanded. Rosa Prince, Corbyn’s semi-authorised biographer, described, with Bracchitta’s help, a tormented family: ‘Corbyn and Bracchitta went round and round in circles for months. She would not send Ben to Holloway School and Corbyn could not bear for him to go to Queen Elizabeth’s … In choosing Queen Elizabeth’s, Bracchitta was aware that she was ending her marriage … Once again, Corbyn had put politics above his relationship.’ That version is clearly incorrect. The marriage ended because of Corbyn’s behaviour – his financial incompetence, his thoughtless absences, his neglect of his family and his apparent misogyny. ‘He told me that the marriage had ended long before the school bit,’ Ken Livingstone recalled. ‘We had a chat at the time and he said his marriage had fallen apart over other things, not the school.’ Like Reg Race, Livingstone had discovered that Corbyn’s ‘authenticity’ was fictitious – a confection for political appearances. He had posed as a man who refused to sell out, albeit he was never heard to advocate higher standards of teaching.

The posturing became even more apparent in July 2016, one year after Corbyn became Labour’s leader. He appeared in a televised interview with the novelist and poet Ben Okri. The premise was Corbyn’s love of literature, but this was totally fabricated. He had only ever read very little. Equally misleading was his declaration: ‘You have to be honest with people. You have to say what you believe to be the truth. If you hide the truth you are very dishonest.’

Up to the present day, Corbyn has concealed or distorted the nature of his close relationships, his personal life and his prejudices. The communists understood the value of those Lenin called ‘useful idiots’ – the well-intentioned idealists in the West who blindly supported the Soviet agenda. Lenin also mastered one critical ruse to grab public support. ‘A lie told often enough,’ he said, ‘becomes the truth.’ He had gone on to adopt Dostoyevsky’s wise observation in Crime and Punishment: ‘They lie and then worship their own lies.’ Considering his long involvement with Corbyn before his ambition to lead Britain materialised, in 2018 Reg Race made a measured judgement about his former friend. Realising that Corbyn was guilty of that same deception, he concluded, ‘He’s not fit to be leader of the Labour Party, and not fit to be Britain’s prime minister.’