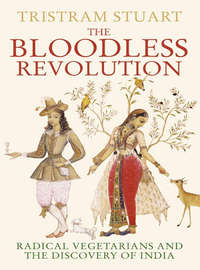

Kitabı oku: «The Bloodless Revolution: Radical Vegetarians and the Discovery of India», sayfa 2

Numerous vegetarian doctors emerged all over Europe, transforming these scientific arguments into practical dietary prescriptions for patients believed to be ailing from over-consumption of flesh. These diet-doctors became conspicuous figures in society, much like the celebrity dieticians of today, but they were also primary movers in pioneering medical research. Meat was almost universally believed to be the most nourishing food, and in England especially, beef was an icon of national identity. It was still common to suspect that vegetables were unnecessary gastronomic supplements and that they were prone to upset the digestive system in perilous ways. The vegetarians helped to alter such suppositions, by presenting evidence that vegetables were an essential nutritional requirement, and that meat was superfluous and could even be extremely unhealthy. The vegetarians thus played a key role in forming modern ideas about balanced diets and put a spotlight on the dangers of eating meat, especially to excess.

Believing that the vegetable diet was healthier and meat was positively harmful invariably led people to the conclusion that the human body was designed to be herbivorous, not carnivorous, and that killing animals was unnatural. Examining natural laws was supposed to provide insights into God’s creational design, independent from scriptural revelation. The new scientific observations were seen to endorse the old theological claims for the origins of the vegetable diet, and it gave added force to the view that human society’s savage treatment of lesser animals was a perversion of the natural order.

These deductions were backed up by changing perceptions of sympathy which became one of the fundamental principles of moral philosophy in the late seventeenth century, and has remained an abiding force in Western culture. The idea of ‘sympathy’ in its modern sense as a synonym for ‘compassion’ was formulated as a mechanical explanation of the archaic idea of sympatheia, the principle – spectacularly adapted to vegetarianism by Thomas Tryon – according to which elements in the human body had an occult ‘correspondence’, like a magnetic attraction, to similar entities in the universe. Descartes’ followers explained that if you saw another person’s limb being injured, ‘animal spirits’ automatically rushed to your corresponding limb and actually caused you to participate in the sense of pain. Although the Cartesians thought that sympathy for animals should be ignored, later commentators argued that the instinctive feeling of sympathy for animals indicated that killing them was contrary to human nature. Vegetarians seized upon the unity of the ‘scientific’, ‘moral’ and ‘religious’ rationales and tried to force people to recognise that eating meat was at odds with their own ethics. Although most people preferred not to think about it, the vegetarians insisted that filling the European belly funded the torture of animals in unpleasant agricultural systems, and ultimately the rape and pillage of the entire world.

All these claims were fiercely repudiated and a distinct counter-vegetarian movement quickly rallied in defence of meat-eating. The intensity as well as the wide proliferation of the debate testifies to just how familiar the vegetarian cause became, and just how challenging most people felt it to be. It threatened to oust man from his long-held position as unlimited lord of the universe – and worse still, to deprive people of their Sunday feasts of roast meat. Leading figures in the medical world accepted some of the vegetarians’ reforms – that people should eat less meat and more vegetables – but urgently asserted that man’s anatomy was omnivorous or carnivorous not herbivorous, and that vegetables alone were unsuitable for human nourishment. Several philosophers, novelists and poets likewise insisted that sympathy for animals was all very well, but should not be taken to the extreme of vegetarianism.

Nevertheless, prominent members of the cultural elite espoused at least some of the views of the vegetarians and inspired a considerable back-to-nature movement in which diet played an important role. The novelist Samuel Richardson allowed the vegetarian ideals of his doctor, George Cheyne, to infiltrate his best-selling novels, Clarissa and Pamela. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, concurring with the anatomical case, argued that the innate propensity to sympathy was a philosophical basis of animal rights, thus spawning a generation of Rousseauists who advocated vegetarianism. The economist Adam Smith took on board the doctors’ discovery that meat was a superfluous luxury and this provided an important cog in the taxation system of his seminal treatise on the free market. By the end of the eighteenth century vegetarianism was advocated by medical lecturers, moral philosophers, sentimental writers and political activists. Vegetarianism had sustained its role as a counter-cultural critique, backed up by evidence that many in the mainstream of society could accept.

The history of vegetarianism adumbrates recent revisionary criticism which questions traditional oppositions between the so-called irrationalism of religious enthusiasts and the ‘Enlightenment’ rationalism of natural philosophers. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the vegetable diet was munched raw at the communal board of the political and religious extremists – but it was also served with silver cutlery at the high table of the Enlightenment to the learned elite.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Europe was dominated by a culture of radical innovation – diverse movements bundled together under the name Romanticism. Hinduism became the object of veneration as a new wave of Orientalists travelled to India, learned Indian languages and translated Sanskrit texts to the delight of Western audiences. Some East India Company servants were so overcome by the benevolence of Indian culture that they relinquished the religion of their fathers and employers to embrace Hinduism as a more humane alternative. This played into the hands of radical critics of Christianity, such as Voltaire, who used the antiquity of Hinduism to land a devastating blow to the Bible’s claims, and acknowledged that the Hindus’ treatment of animals represented a shaming alternative to the viciousness of European imperialists. Even those more dedicated to keeping their Christian identity, such as the great scholar Sir William Jones, found themselves swayed by the doctrine of ahimsa, seeing it as the embodiment of everything the eighteenth-century doctors and philosophers had scientifically demonstrated.

As the ferment of political ideas brewed into revolutionary fervour in the 1780s, the vegetarian ideas from former centuries were incorporated once again into a radical agenda. Hinduism was held up as a philosophy of universal sympathy and equality which accorded with the fundamental tenet of democratic politics and animal rights. The rebel John Oswald returned from India inflamed with outrage at the violent injustice of human society and immersed himself in the most bloodthirsty episodes of the French Revolution. Others developed Rousseau’s back-to-nature movement and lost their heads on the guillotine defending their vegetarian beliefs. The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley joined an eccentric network of nudist vegetarians who were agitating for social revolution and immortalised their ideas in a series of vegetarian poems and essays. As atheism waxed, the anthropocentric bias of European Christianity was eroded, and humans were forced to acknowledge that they were more closely related to animals than was entirely comfortable. Utopian reformers still had the model of primeval harmony seared into their imaginations even though many of them regarded Eden as no more than a myth, so they learned to treat Judaeo-Christianity as an anthropological curiosity and paved the way for modern ideas about humanity and the environment.

As environmental degradation and population growth became serious problems in Europe, economists turned to the pressing question of limited natural resources. Many realised that producing meat was a hugely inefficient process in which nine-tenths of the resources pumped into the animal were wastefully transformed into faeces.

Utilitarians argued that since the vegetable diet could sustain far more people per acre than meat, it was much better equipped to achieve the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Once again the enormous populations of vegetarian Indians and Chinese were held up as enlightened exemplars of efficient agronomics. Such calculations eventually led to Thomas Malthus’ warnings that human populations inexorably grew beyond the capacity of food production, and that famine was likely to ensue.

By the early nineteenth century most of the philosophical, medical and economic arguments for vegetarianism were in place, and exerting continual pressure on mainstream European culture. In the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the ideas inevitably transformed, but continuities can be traced to the present day. Figures as diverse as Adolf Hitler, Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy developed the political ramifications of vegetarianism in their own ways, and continued to respond to India’s moral example.

When studying ideas that people formulated hundreds of years ago, it is important to understand them on their own terms, irrespective of whether they are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ according to present-day understanding, because to do so allows them to provide insight into assumptions that still prevail in modern society – of which, in their nature, we are commonly unaware. The remarkable and long under-appreciated lives of early vegetarians are inroads into uncharted areas of history; they simultaneously shed light on why you think about nature the way you do, why you are told to eat fresh vegetables and avoid too much meat, and how Indian philosophy has crucially shaped those thoughts over the past 400 years.

* Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writers generally used ‘Man’ to denote ‘mankind’ comprising both genders, usually with a patriarchal bias. It would be a distortion to avoid using their term.

PART ONE Grass Roots

ONE Bushell’s Bushel, Bacon’s Bacon and The Great Instauration

Driving out of London over Highgate Hill on a cold March day in 1626, Sir Francis Bacon noticed spring snow still lying on the ground and seized the opportunity to test whether ‘flesh might not be preserved in snow, as in salt’. Bacon descended from his carriage in a flourish of compulsive inquisitiveness, purchased a hen from a poor woman, made her gut it, and then stuffed it with snow himself. Before he could publish the results of this, his last experiment, the snow chilled Bacon’s own flesh, and he was struck by a coughing fit so severe he could not return home. As he lay in the damp bed in the nearby house of his friend the Earl of Arundel, his condition worsened, and within days Bacon, one of England’s greatest philosophers, was dead.1

Born in 1561, Bacon had struggled to the very top of the political ladder; he had been a member of Queen Elizabeth’s council and Lord Chancellor to King James VI and I. Despite his relatively modest background as the grandson of a sheep-reeve, he had been knighted and ennobled with the titles of Baron Verulam and Viscount St Albans. Above all, he was respected throughout Europe for philosophical works in which he envisaged an intellectual project of limit-defying scale. By gaining comprehensive knowledge of the natural world, Bacon believed that people could improve their control over the environment until eventually they would reinstate the felicity that Adam enjoyed in Eden. In the title of his unfinished work, The Great Instauration (from the Latin Instauratio – restoration, inauguration), he signified that his vision was the beginning of the restitution of mankind’s lost power. His audacious optimism fired the imagination of the keenest minds of the ensuing centuries, and his name became the touchstone of the Enlightenment. When King James first read Bacon’s writings he proclaimed that ‘yt is like the peace of God, that passeth all understanding’.2

Bacon’s escapade with the frozen chicken was not an isolated whim. He had been studying the properties of food for years and in 1623 published in Latin The Great Instauration’s third part: The History Naturall and Experimentall, Of Life and Death. Or the Prolongation of Life. The quest to discover the secret to long life had been an obsession since ancient times, and Bacon himself considered it the ‘most noble’ part of medicine.3 For Bacon, no less than people today, diet took centre-stage. Though ironically his investigations into the ‘preservation of flesh’ actually caused his own flesh to perish, Bacon hoped that discovering the ideal food would help lead men back to their original perfection.

Bacon noticed that it was healthy to eat plenty of fruit and vegetables on a daily basis. But if it was longevity you were after, he advised his readers to ignore the usual chatter about the Golden Mean and go for either of the extremes. Strengthen your constitution by undergoing a ‘strict Emaciating Dyet’ of biscuit and guaiacum tree resin: this would weaken you in the short term, but set you up for a long life. Going to the other extreme, Bacon agreed with Celsus, the first-century AD medical encyclopaedist, that gastronomic excess could also be good for you. This amusing mandate for indulgence – which eighteenth-century medics rallied around when their appetites came under fire from the vegetarian doctors – no doubt informed the approving tone of the contemporaneous biographer, John Aubrey, when he wrote that Bacon’s one-time assistant, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, periodically over-indulged, getting himself blind drunk at least once a year. Dying at the age of ninety-two, Hobbes was later wilfully enrolled by eighteenth-century vegetarians as a fine example of the benefits of temperance.4

‘Man, and Creatures feeding upon Flesh, are scarcely nourished with Plants alone,’ wrote Bacon in 1623. ‘Perhaps, Fruits, or Graines, baked, or boyled, may, with long use, nourish them;’ he added. ‘But Leaves, of Plants, or Herbs, will not doe it.’ Surviving exclusively on leaves and greens (‘herbs’ meant herbaceous plants including things like cabbage) had already been attempted with catastrophic effects by the Foliatanes, a convent of ascetic nuns who fed on nothing but foliage. But Bacon did allow that humans and carnivores could survive on vegetables if the ingredients were well chosen, and his Latin original shows him to have been even more open to the vegetarian diet than his disconcerted posthumous translators made it sound.5 Bacon noticed that there was substantial statistical evidence that vegetarianism was one of the extremes that could aid longevity: Pythagoras, the sixth-century BC Greek philosopher renowned for his theorem on right-angled triangles, also taught his disciples to abstain from meat, and Pythagoreans such as Apollonius of Tyana ‘exceeded an hundred yeares; His Face bewraying no such Age’. Indeed, Bacon catalogued numerous vegetarians recorded in history who had lived unusually long lives: the desert-dwelling Jewish sect of vegetarian Essenes, the Spartans, the Indians and plenty of Christian ascetics. ‘A Pythagoricall, or Monasticall Diet, according to strict rules,’ concluded Bacon, ‘seemeth to be very effectual for long life.’

So while Hobbes swallowed whole Bacon’s aphorisms about indulgence, another flamboyant young male acolyte, Thomas Bushell (1594–1674), was ruminating over his master’s approbation of the vegetarian way. Thomas Aubrey described both Hobbes and Bushell scurrying along behind Bacon transcribing his thoughts during strolls in his garden – each preparing to carry Bacon’s legacy forward in their own divergent ways.

In 1621 Bacon’s glittering political career came to an abrupt end. He was made the scapegoat in a political tussle about monopolies and the victim of a personal attack by his rival Edward Coke. Left to the mercy of Parliament by the King, Bacon was accused of taking bribes; he was fined £40,000, briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London and banished from court in disgrace. In the wake of this scandal there followed more severe allegations: that Bacon was a sodomite and paid his young male servants, Bushell among them, for sex. Satirical verses circulated, laughing at the matching of their names: Bacon was ‘A pig, a hog, a boar, a bacon/ Whom God hath left, and the devil hath taken’, while his servant pecked at his bushel of grain, but ‘Bushell wants by half a peck the measure of such tears/ Because his lord’s posteriors makes the buttons that he wears’. (The buttons refer to the garish fashion of embellishing suits with buttons, leading to the double-entendre nickname ‘buttoned Bushell’.)6

Taking his fate stoically, Bacon devoted himself to philosophical enquiries, but Bushell – who had joined Bacon’s household at the age of fifteen, risen to be his seal-bearer and was entirely dependent on his patron – faced despair. Following Bacon’s fall from grace and subsequent death, Bushell was plunged into dejected remorse. Lurching from a life of wanton profligacy, in which his greatest achievement had been running up enormous debts and attracting the attention of James I for the gorgeousness of his attire, he left behind him London’s gaming houses, bawdy Shakespearean plays and buxom whores of Eastcheap, and dramatically refashioned himself as the ‘Superlative Prodigall’.

‘Thomas Bushell, the Superlative Prodigal’ from Thomas Bushell, The First Part of Youths Errors (1628)

The young man took his penitence to anchoritic extremes. In his later writings, Bushell described how he first retired to the Isle of Wight disguised as a fisherman, and afterwards to the Calf of Man (an islet just off the Isle of Man) where he took up residence on the desolate summit of a cliff 470 feet above the Irish Sea. There, he said, ‘in obedience to my dead Lord [Bacon’s] philosophical advice, I resolved to make a perfect experiment upon myself, for the obtaining of a long and healthy life.’ He shunned meat and alcohol, living instead on a ‘parsimonious diet of herbs, oil, mustard and honey, with water sufficient, most like to that [of] our long liv’d fathers before the flood, as was conceiv’d by that lord, which I most strictly observed, as if obliged by a religious vow’.

The austerity of Bushell’s diet was clearly rooted in the Christian (and pre-Christian) tradition of abstinence from meat and monastic penitence. By imposing strictures on the body, it was believed, the soul would be regenerated and cleansed of sin. And it was meat and alcohol, above all, that were identified as the principal items of luxury. The problem for Bushell was that in Protestant England ascetic fasting was seen as a superstitious vestige of Catholicism. By giving up meat and living like a monk he risked being accused of having secret Catholic sympathies. In his confessions, The First Part of Youths Errors (1628), Bushell vigorously defended himself: if all the saints – Anthony, Augustine, Jerome, Paul the hermit and the Apostles themselves – had been ascetics, he demanded, then why shouldn’t he, a terrible sinner, be one as well?7

Bacon too was aware of how suspicious his predilection for vegetables could seem. Regardless of being called a Catholic, Bacon was afraid he would be accused of sympathising with the medieval vegetarian heretics, the Manicheans and Cathars, whom the Inquisition had genocidally suppressed with fire and sword. Anxious to avoid such a fate, Bacon issued repeated disclaimers: ‘Neither would we be thought to favour the Manichees, or their diet, though wee commend the frequent use of all kindes of seedes, and kernels, and roots … neither let any Man reckon us amongst those Hereticks, which were called Cathari.’ Bacon was trying to shift discussions of diet away from its old heretical connotations into the new idiom of enlightened philosophy. His opinions, he insisted, were based on empirical facts and not on religious dietary taboos.8

Happily, Bacon’s healthy vegetable diet appears to have done Bushell a world of good. By the time he was buried in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey in 1674 at the fine old age of eighty, Bushell had become a legendary figure, and is still remembered today as the Calf of Man’s most famous inhabitant. For a while, he was also rich. Having come down from his cliff, he pursued Bacon’s practical tip on reclaiming silver and lead mines in Wales and established his own mint in Aberystwyth. God was so pleased with his vegetarian penitence, he claimed, that He gave Bushell power to subdue the ‘Subteranean Spirits’ which usually hindered mining projects. With the profits that flowed from the earth, he proclaimed his intention to realise Bacon’s plans for a ‘Solomon’s House’ – the utopian establishment depicted in Bacon’s unfinished work, New Atlantis. Bacon had imagined an ideal colony where scientific endeavour (including a primitive form of genetic engineering) was enhanced by the inhabitants’ rigorous lifestyle, some of them purifying their bodies by living in three-mile-deep caves below the mountains. Bushell’s institution was not quite what Bacon had imagined. It was more like a philanthropic dining facility for his miners, where instead of being fed the complete meal Bacon had devised – a fermented-meat drink – they were fed on Bushell’s own meagre diet of penitential bread and water.

Bushell himself retreated, meanwhile, to his estate at Road Enstone, near Woodstock in Oxfordshire, where he created a ‘kind of paradise’ in a grotto garden around a cave which became famous for a natural spring generating a series of spectacular hydraulic contraptions. He was no doubt inspired by Bacon’s cave-dwelling multi-centenarian wise men and by the ‘paradise’ garden at Bacon’s mansion in Gorhambury where the pair used to spend hours in meditation. In his new abode Bushell kept up his old dietary resolve, writing that he still ‘observ’d my Lords prescription, to satisifie nature with a Diet of Oyle, Honey, Mustard, Herbs and Bisket’. King Charles I and Queen Henrietta visited Bushell in his grotto in 1636, and for their pleasure he organised the performance of a masque about a vegetarian prodigal hermit. The Queen expressed her appreciation by installing an extremely rare Egyptian mummy in Bushell’s damp grotto home (where it slowly went mouldy and was lost to posterity).

When civil war broke out in 1642, Bushell roused himself from his tranquil retreat. As political affiliations polarised those who questioned and those who believed subjects had no right to question, Bushell remained fervently loyal to King Charles. Bacon had foreseen the political turmoil and spent his career defending the royal prerogative; faithful to Bacon as always, Bushell became a mainstay of the Cavaliers’ military campaign against the Roundheads. He turned his miners into the King’s lifeguard, bankrolled the Royalist army with silver and a hundred tons of lead-shot from his mines, put down a mutiny in Shropshire, and defended (yet another island) Lundy in the Bristol Channel. Eventually surrendering to the onslaught of the Parliamentary army, he was arrested and seriously wounded in the head, but then attained the protection of Lord Fairfax. With many of his loans unsettled other than by a quaint but otherwise worthless thank-you letter from King Charles, Bushell went back to his garden, as Horace to his Sabine Farm and the poet Andrew Marvell to Nun Appleton, rejecting the anarchy of Cromwell’s interregnum in preference for his own private Eden.9

Bushell’s dietary strictures followed an ancient Christian tradition which conceived of vegetarianism as a back door to regaining paradisal perfection. Like several Church fathers, the ascetic St Jerome (AD c.347– 420) – revered for plucking a painful thorn from a lion’s paw and composing the Latin Bible in his penitential cave – associated the gluttony of flesh-eating with Adam’s intemperate eating of the forbidden fruit. If people wanted to undo the curse of the Fall, they would have to start by abstaining from flesh: ‘by fasting we can return to paradise, whence, through fullness, we have been expelled.’ ‘At the beginning of the human race we neither ate flesh, nor gave bills of divorce, nor suffered circumcision,’ said Jerome. These were concessions granted after the Flood, ‘But once Christ has come in the end of time,’ he said, ‘we are no longer allowed divorce, nor are we circumcised, nor do we eat flesh’.10 This provided a theological rationale for relinquishing meat which lasted for centuries. As Sir John Pettus suggested in 1674, we ‘multiply Adams transgression by our continued eating of other creatures, which were not then allowed to us’.11

This tradition had come under fire ever since the Protestants had split from the Roman Church. John Calvin (1509–64), co-founder of the Reformation, had tried to untangle such literal-minded dietary loopholes. He cast doubt over the vegetarianism of the early patriarchs by pointing out that God gave Adam and Eve animal skins to wear when he ejected them from Eden’s balmy realm, and that ever since the time of Cain and Abel people had sacrificed animals. But even if they didn’t eat the animals they sacrificed, he stressed, the important point was that God did eventually give ‘to man the free use of flesh, so that we might not eat it with a doubtful and trembling conscience’. Anyone who thought mankind should be vegetarian was being blasphemously ungrateful for God’s generosity. He had one message for such hyper-scrupulous quibblers: shut up and eat up.12 But this was not enough to stem the longing for perfection, even in Protestant countries, and Bushell was one of many who still hoped to reclaim his lost innocence by abstaining from flesh.

In the masque he laid on for the King and Queen, Bushell depicted (and perhaps played) the part of the vegetarian hermit – clearly modelled on himself – who claims to have lived in the same Oxfordshire cave and subsisted on the same vegetable diet ever since the time of Noah. The hermit tells his audience he lives in a reconstructed Golden Age, ‘In which no injuries are meant or done’. The masque ended with the hermit inviting the King to join his world (and forget for a while the looming political crisis) by sharing in the feast of home-grown fruit.13

The Golden Age, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Bushell was indulging in the common feeling that the biblical story of original harmony was analogous to the classical Greek and Roman myth of the Golden Age, when justice reigned, iron was yet to be invented and no animals were slaughtered. In 1632, just before Bushell’s masque, the travelling poet George Sandys had published his extremely influential translation and commentary on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Sandys portrayed the Golden Age menu of wild blackberries, strawberries, acorns and ‘all sorts of fruit’ in a much more appetising light than translators hitherto, and added enthusiastically that ‘this happy estate abounding with all felicities, assuredly represented that which man injoyed in his innocency: under the raigne of Saturne, more truly of Adam.’14 Eating meat, he added, was ‘a priviledge granted after to Noah; because [‘hearbes and fruits’] then had lost much of their nourishing vertue’. Meat-eating, according to this reasoning, was an unfortunate consequence of the Flood. In the climactic finale of Metamorphoses, Pythagoras comes forward and delivers a lengthy diatribe against eating animals – ‘How horrible a Sin, / That entrailes bleeding entrailes should intomb! / That greedie flesh, by flesh should fat become!’ Sandys noted that Pythagoras’ vegetarianism was an attempt to reinstate the peacefulness of the Golden Age because killing animals proceeded ‘from injustice, cruelty, and corruption of manners; not knowne in that innocent age’.15 Pythagoras’ example was an inspiration to early vegetarians like Bushell.

Giving up meat altogether may have been rather quirky in early seventeenth-century England, and Bushell was well aware that his notions could be mistaken for ‘the Chymera of a phanatick brain’.16 He further risked his reputation by successfully lobbying the government to release from prison several members of religious groups who were also trying to reinstate the conditions and even the diet of Eden, such as the Rosicrucians, the Family of Love and the Adamites (who took the Adamic lifestyle to its extreme by shedding their clothes and living in the naked purity of Eden before the figleaves).17

It may seem as if Bushell had by this time descended into a religious dream world, but his extreme diet was endorsed by scientific rigour. Bushell’s immersion into vegetarianism was an act of religious fervour, but it was simultaneously the realisation of a Baconian project: he presented himself as a human guinea-pig in Bacon’s ‘perfect experiment’ for lengthening human life on a vegetarian diet. As Bushell said, his dietary attempt to gain a long and healthy life was based on that of ‘our long liv’d fathers before the flood’. It was statistically evident that the average age of the ‘antediluvian’ patriarchs was in excess of 900 years, topped by Adam’s descendant, Methuselah, who lived to 969 (Genesis 5). What – everyone wanted to know – was the secret of their longevity?18 Once permission to eat meat was granted after the Flood, human life expectancy plummeted from 900 to the current average of around 70. It seemed at least plausible to the enquiring mind that it was eating meat that had curtailed human life so dramatically;19 perhaps by relinquishing it one could regain some of those lost years. This may sound like it competes in crankiness with today’s diet-doctors, but few then dared doubt the basic facts set out in the Bible. Even the philosopher René Descartes seems to have believed it. It may seem surprising that religious extremes and experimental philosophy coincided in such a spectacular way, but it was a trend that would continue for at least two centuries. Bacon and Bushell raised many of the questions about vegetarianism that dominated the ensuing debate.