Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «War Cry»

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Orion Mintaka (UK) Ltd 2017

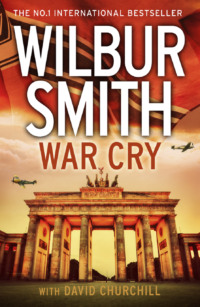

Cover layout design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017 Cover photographs © Collaboration J.S. except www.Shutterstock.com (Brandenburg Gate).

Wilbur Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007535897

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780007535880

Version: 2018-10-25

Dedication

I dedicate this book War Cry to my wife Mokhiniso who has been my total joy and inspiration over these last many decades of my life and all those others yet to come. I love you, my Fireball.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Two months had passed since …

Leon Courtney sank into the welcome …

Three days before Christmas, as they were …

When Saffron reached him they did not …

Frescobaldi knew he had another magazine …

About the Author

Also by Wilbur Smith

About the Publisher

Two months had passed since war had been declared and the autumn sun that shone down from the clear blue skies over Bavaria was so glorious that it seemed to cry out for beer to be drunk and songs to be sung in hearty, joyful voices. But the Oktoberfest had been cancelled and the Double Phaeton limousine proceeding up the short drive of the villa in Grünwald, just outside Munich, bore tidings that were anything but joyous.

The car pulled to a halt. Its chauffeur opened the passenger door to allow a distinguished gentleman in his late sixties to disembark and a uniformed butler admitted him into the house. A moment later, Athala, Countess of Meerburg, looked up as the family lawyer Viktor Solomons was shown into the drawing room. His hair and beard might now be silver and his stride was less vigorous than it had once been, but the impeccable tailoring of his suit, the gleaming white of his perfectly starched collar and the flawless shine of his shoes reflected a mind that was still as precise, as sharp and as insightful as ever.

Solomons stopped in front of Athala’s chair, gave a respectful little nod of the head and said, ‘Good morning, Countess.’

His mood seemed subdued, but that was only to be expected, Athala reminded herself. Solomons’s beloved son Isidore was away at the front. No parent could ever be light-hearted knowing that their child’s very survival now lay at the mercy of the gods of war.

‘Good morning, Viktor, what an unexpected pleasure to see you. Do please sit down.’ Athala extended a dainty hand towards the chair opposite her. Then she turned her attention towards the butler who had shown the guest in and was now awaiting further instruction. ‘Some coffee, please Braun, for Herr Rechtsanwalt Solomons. Would you like some cake, Viktor? A little strudel, perhaps?’

‘No thank you, Countess.’

There was a sombre tone to Solomons’s voice, Athala realized, and he seemed uncharacteristically reluctant to look her in the eye. He has bad news, she thought. Is it the boys? Has something happened to one of them?

She told herself to remain calm. It would not do to betray one’s fears, especially not while a servant was still in the room. ‘That will be all, Braun,’ she said.

The butler departed. Athala felt a sudden desire to postpone the bad tidings for just a few seconds. ‘Tell me, how is Isidore getting on? I hope he’s safe and well.’

‘Oh yes, very well thank you, Countess,’ Viktor replied, with a distracted air, as though his mind was not fully engaged. But he took such pride in his beloved son that he could not resist adding, ‘You know, Isidore’s division is commanded by Crown Prince Wilhelm himself. Imagine that! We received a letter from him just last week to say that he has already seen his first action. Apparently, his major declared that he conducted himself admirably under fire.’

‘I’m sure he did. Isidore is a fine young man. Now … what is it, Viktor, why are you here?’

Solomons hesitated a second to gather his thoughts and then sighed, ‘I fear there is no other way of saying this, Countess. The War Office in Berlin informed me today that your husband, Graf Otto von Meerbach, is dead. General von Falkenhayn felt that it was better that you should hear the news from someone you knew, than simply receive a telegram message, or a visit from an unknown officer.’

Athala slumped back against her chair, eyes closed, unable to say a word.

‘I know this must be very distressing,’ Solomons went on, but distress was actually the last thing on her mind. Her overwhelming feeling was one of relief. Nothing had happened to her sons. And finally, after all these years, she was free. There was nothing that her husband could do to hurt her any more.

Athala controlled herself. She had been trained from her earliest girlhood to compose her fine, porcelain features into an image of calm, aristocratic elegance, no matter what the circumstances. It was now second nature to hide her true feelings behind that mask, just as the waters of a pond cover the constantly paddling feet that enable a swan to glide with such apparent ease across its glittering surface.

‘How did he die?’ she asked.

‘In an air crash. I have been informed that His Excellency was engaged in a mission of the greatest importance to the German Empire. Its details are classified, but I am authorized to inform you that the crash occurred over British East Africa. The Count was flying aboard his magnificent new airship the Assegai. This was her maiden voyage.’

‘Did the British shoot him down, then?’

‘I do not know. Our ambassador in Bern was informed by his British counterpart merely that the Count had died. This was a gesture of courtesy, in honour of your late husband’s eminence. I gather, however, that the British do not have any Royal Flying Corps units in Africa, so we must assume that this was an accident of some kind. The gas used to elevate these “dirigibles” can, apparently, be very unstable.’

Athala looked Solomons straight in the eye and very calmly said, ‘Was she on board the Assegai at the time?’

The lawyer did not need to be told who ‘she’ was. Nor, for that matter, would anyone remotely acquainted with German high society. Count von Meerbach had long been a notorious philanderer, but in recent years he had become obsessed with one particular mistress, a ravishing beauty, with lustrous sable hair and violet-blue eyes called Eva von Wellberg. The Count had begged Athala to divorce him, so that he could make the Wellberg woman his wife, but she had refused. Her Catholic faith would not allow her to end her marriage. And so they had come to an arrangement. Countess Athala lived, with their two young sons, in her perfectly proportioned classical villa in the chic little town to the southwest of Munich where the smartest elements of Bavarian society could be found. Meanwhile, Count Otto had retained his family castle on the shores of the Bodensee. And there he kept his mistress, or as Athala thought of her, his whore, and saw his sons on the rare occasions he was able, or remotely willing to spare the time to attend to them.

‘The Assegai was housed within the grounds of the Meerbach Motor Works,’ Solomons said, referring to the gigantic industrial complex on which the family fortune was based. ‘I am told by senior company officials who were present at the airship’s departure that a woman was seen going aboard her. I was also informed by the War Office that the Assegai went down with all hands. No one survived.’

Athala allowed a slight, bitter smile to cross her face. ‘I will not even pretend to be sorry that she is dead.’

‘Nor can I pretend to criticize you for that. I am well aware how much you have suffered on her account.’

‘Dear Viktor, you are always so kind, and so fair. You are …’ She paused to correct herself, ‘You were my husband’s lawyer, yet you have never done anything to hurt me.’

‘I am the family’s lawyer, Countess,’ Solomons gently corrected her. ‘And as long as you were, and remain part of the von Meerbach family, then I will always consider you my client. Now, may I ask, are you ready to discuss any of the consequences of your husband’s tragic demise?’

‘Yes, yes I am,’ said Athala and then, for reasons she could not quite explain, she suddenly felt the loss to which she had been numb up to that point. For all that she had suffered, she had always prayed that one day her husband might see the error of his ways and devote himself to his family. Now all hope of that had gone. She began to cry and started rummaging through the bag at her feet, trying to find a handkerchief.

‘May I?’ asked Solomons, reaching into his pocket.

She waved him away, shaking her head, not trusting herself to speak. Finally she found what she was looking for, pressed the handkerchief to her eyes, dabbed her nose, took a deep breath and said, ‘Please forgive me.’

‘My dear Countess, you have just lost your husband. Whatever difficulties you may have faced, he was still the man you married, the father of your children.’

She nodded and ruefully said, ‘It seems that I do not have a heart of stone after all.’

‘I, for one, never supposed that you did. Not for a single moment.’

She gave him a nod of thanks and then said, ‘Please continue … I believe you were going to describe the consequences of …’ She could not bring herself to use the word ‘death’ and so just said, ‘Of what has occurred.’

‘Quite so. There cannot be a funeral, sadly, for if the body has been recovered, the British will by now have buried it.’

‘My husband died serving his country overseas,’ Athala said, straightening her back and resuming her air of poised composure. ‘That is to be expected.’

‘Indeed. But I think it would be entirely appropriate, indeed expected, to have a service of remembrance, perhaps at the Frauenkirche in Munich, or you may feel that either the family chapel at Schloss Meerbach, or even a service at the Motor Works, would be more appropriate.’

‘The Frauenkirche,’ said Athala, without a moment’s hesitation. ‘I don’t think a factory is a suitable location at which to commemorate a Count of the German Empire and the chapel at the schloss is too small to accommodate the numbers of people who will wish to attend. Could someone from your firm liaise with the Archbishop’s office, to secure a suitable date and assist with the administration of the event?’

‘Of course, Countess, that would be no trouble. Might I suggest the Bayerischer Hof for the reception after the service? If you give the hotel manager your general requirements, the hotel staff will know exactly how best to provide exactly what you need.’

‘I’m afraid I can’t even begin to think about that just now.’ Athala closed her eyes, trying to put the jumble of thoughts and emotions in her head in order and then asked, ‘What will become of my sons and I?’

‘Well, the extent and variety of the Count’s possessions mean that his will is unusually complex. But the essential facts are that the family estate here in Bavaria, and a majority share in the Motor Works, all go to your eldest son, Konrad, along with the title of Graf von Meerbach. Your younger son, Gerhard, will have a smaller shareholding in the company. The various properties and the income they generate will be held in trust for each son until he is twenty-five. Prior to that point, they will each receive a generous allowance, plus the cost of their education, of course. Any additional expenditure will have to be approved by their trustees.’

‘And who will they be?’

‘In the first instance, you and I, Countess.’

‘My God, fancy Otto allowing me such power.’

‘He was a traditionalist. He felt that a mother should take charge of her children’s upbringing. But you will note that I said “in the first instance”. Once Konrad is twenty-five, and takes control of the family’s affairs, he will also assume the role of trustee to his brother, who will then be eighteen years old.’

‘So for seven years, Gerhard will have to go cap in hand to Konrad if he ever needs anything?’

‘Yes.’

Athala frowned. ‘It worries me that one brother should have so much power over the other.’

‘His Excellency believed very strongly that a family, like a nation, required the strong leadership of a single man.’

‘Didn’t he just … I take it that I am provided for.’

‘Oh yes, you need not worry on that score. You will retain your own family money, added to which you will keep all the property, jewellery, artworks and so on that you received during your marriage, and receive a very generous annual allowance for the rest of your life. You will also have a place on the board.’

‘I don’t care about the damn board,’ Athala said. ‘It’s my boys that I worry about. Where are we meant to live?’

‘It is entirely up to you, whether you wish to reside here in Grünwald, or at Schloss Meerbach, or both. His Excellency has set aside monies that are to be spent on the maintenance of the castle and its estate, and on employing all the staff required to maintain the standards he himself demanded. You will be the mistress of Schloss Meerbach once again, if you choose to be so.’

‘Until Konrad’s twenty-fifth birthday …’

‘Yes, he will be the master then.’

When Solomons had gone, Athala went upstairs to the playroom where Gerhard was playing. She looked on him as a gift from God, an unexpected blessing whose birth had brought a rare moment of joy to a marriage long past rescuing. Gerhard had been conceived on the very last night that Athala and Otto had slept together. It had been a short, perfunctory coupling and he had been away with Fräulein von Wellberg on the night Gerhard was born. But that only made her baby all the more precious to Athala.

She wondered how she was going to explain to him that his father was dead. How did one tell a three-year-old that sort of thing? For now, she didn’t have the heart to interrupt Gerhard while he played with the wooden building bricks that were his favourite toy.

Athala always found her son fascinating to observe as he arranged the brightly coloured bricks. He had an instinctive grasp of symmetry. If he placed one brick of a certain colour or shape on one side of his latest castle, or house, or farm (Gerhard always knew exactly what he was building), then another, identical one had to go on the opposite side.

She leaned over and kissed his head. ‘My little architect,’ she murmured, and Gerhard beamed with pleasure, for that was his favourite of all her pet names for him.

I will tell him, Athala told herself, but not yet.

She gave the news to both her boys after Konrad had come home from school. He was only ten, but already regarded himself as the man of the house. As such, he made a point of not showing any sign of weakness when told that the father he took after so strongly was dead. Instead he wanted to know all the details of what had happened. Had his father been fighting the English? How many of them had he killed before they got him? When Athala had been unable to give him the answers he required, Konrad flew into a rage and said she was stupid.

‘Father was quite right not to love you,’ he sneered. ‘You were never good enough for him.’

On another day, Athala might have smacked him for that, but today she let it go. Then Konrad’s fury abated as fast as it had risen and he asked, ‘If Father is dead, does that mean that I am the Count now?’

‘Yes,’ said Athala. ‘You are Graf von Meerbach.’

Konrad gave a whoop of joy. ‘I’m the Count! I’m the Count!’ he chanted, marching around the playroom, like a stocky little red-headed guardsman. ‘I can do whatever I want and nobody can stop me!’

He came to a halt by Gerhard’s building, which had risen, brick by brick, until it was almost as tall as its maker.

‘Hey Gerdi, look at me!’

Gerhard looked up at his big brother, smiling innocently.

Konrad kicked Gerhard’s wonderful construction, scattering its bricks across the playroom floor. Then he kicked it again, and again until it was completely obliterated, and nothing remained but the colourful rubble carpeting the room.

Gerhard’s little face crumpled in despair and he ran sobbing to his mother.

As she wrapped her arms around her baby, she looked at the boy count now standing proudly over the destruction he had wreaked and she realized with bitter despair that she had been freed from her husband, only to be enslaved anew by her even more terrible son.

The skinny little girl wore a pair of jodhpurs that flapped around her thighs, for she lacked the flesh with which to fill them. Her short, black bobbed hair, which was normally unconstrained by bands or clips of any kind, had been pinned into a little bun, to be worn beneath her riding hat. Her freckled face was tanned a golden brown and her eyes were the clear, pure blue of the African skies that had looked down upon every day of her life.

All around her the grassy hills, garlanded with sparkling streams, stretched away to the horizon as if the Highlands of Scotland had been transported to the Garden of Eden: a magical land of limitless fertility, incomprehensible scale and thrilling, untamed wildness. Here leopards lounged in the branches of trees that were also home to chattering monkeys and snakes, like the shimmering, iridescent green mamba, or the shy but fatally poisonous boomslang. The head-high grass hid lions sharp in fang and claw and, even deadlier still, the buffalo, whose horns could cut deep into a man’s guts as easily as a sewing needle through fine linen.

The girl barely gave a thought to these hazards, for she knew no other world than this and besides, she had much more important things on her mind. She was stroking the velvet muzzle of her pony, a Somali-bred chestnut mare from which she had been inseparable ever since she had received it as her seventh-birthday present, eight months ago. The horse was called Kipipiri, which was both the Swahili word for ‘butterfly’ and the name of the mountain that stood tall on the eastern horizon, shimmering in the heat haze like a mirage.

‘Look, Kippy,’ the girl said, in a low, soothing murmur. ‘Look at all the nasty boys and their horrid stallions. Let’s show them what we can do!’

She stepped around to the side of the pony and, waving away the offer of a leg-up from her groom, put one foot into the nearest stirrup, pushed off it and sprang up into the saddle as nimbly as a jockey on Derby Day. Then she leaned forward along Kipipiri’s neck, stroking her mane, and whispered in her ear, ‘Fly, my darling, fly!’

Possessed by an exhilarating swirl of emotions in which pride, anticipation and giddy excitement clashed against nervousness, apprehension and a desperate longing not to make a fool of herself, the girl told herself to calm down. She had long since learned that her beloved Kippy could sense her emotions and be affected by them and the very last thing she needed was a nervous, skittish, over-excited mount. So she took a long deep breath, just as her mother had taught her, before letting the air out slowly and smoothly until she felt the tension ease from her shoulders. Then she sat up straight and kicked the pony into a walk, stirring up the dust from the peppery red earth as they moved towards the starting gate of the show-jumping ring that had been set up on one of the fields of the Wanjohi Valley Polo Club for its 1926 gymkhana.

The girl’s eyes were fixed on the fences scattered at apparently random points around the ring. And a single thought filled her mind: I am going to win!

A loudspeaker had been slung from one of the wooden rafters that held up the corrugated iron awning over the clubhouse veranda. The harsh, tinny sound of a man’s amplified voice burst from it, saying, ‘Now the final competitor in the twelve-and-under show jumping, Miss Saffron Courtney on Kipi-pipi-piri …’ Silence fell for a second and then the voice continued, ‘Awfully sorry, few too many pips there, I fear.’

‘And a few too many pink gins, eh, Chalky!’ a voice called out from among the spectators lounging on the wooden benches that were serving as spectator seating for the annual gymkhana the polo club laid on for its members’ children.

‘Too true, dear boy, too true,’ the announcer confessed, and then continued, ‘So far there’s only been one clear round, by Percy Toynton on Hotspur, which means that Saffron’s the only rider standing between him and victory. She’s much the youngest competitor in this event, so let’s give her a jolly big round of applause to send her on her way.’

A ripple of limp clapping could be heard from the fifty or so white settlers who had come to watch their children compete in the gymkhana, or who were simply grasping any opportunity to leave their farms and businesses and socialise with one another. They were drowsy with the warmth of the early afternoon sun and the thin air, for the polo fields lay at an altitude of almost eight thousand feet, which seemed to exaggerate the effect of their heroic consumption of alcohol. A few particularly jaded, decadent souls were further numbed by opium, while those who were exhibiting overt signs of energy or agitation had quite likely sniffed some of the cocaine that had recently become as familiar to the more daring elements in Kenyan society as a cocktail before dinner.

Saffron’s mother Eva Courtney, however, was entirely clear-headed. Seven months pregnant, having had two miscarriages since her daughter’s birth, she had been forbidden anything stronger than the occasional glass of Guinness to build up her strength. She looked towards the jumps that had been set up on one of the polo fields, whispered, ‘Good luck, my sweet,’ under her breath, and squeezed her husband’s hand.

‘I just hope she doesn’t have a fall,’ she said, her deep violet eyes heavy with maternal anxiety. ‘She’s only a little girl and look at the size of some of those jumps.’

Leon Courtney smiled at his wife. ‘Don’t you worry, darling,’ he reassured her. ‘Saffron is your daughter. Which means she’s as brave as a lioness, as pretty as a pink flamingo … and as tough as an old bull rhino. She will come through unscathed, you mark my words.’

Eva Courtney smiled at Leon and let go of his hand so that he could get to his feet and walk down towards the polo field. That’s my Badger, she thought. He can’t bear to sit and watch his girl from a distance. He has to get close to the action.

Eva had given Leon the nickname Badger one morning a dozen years earlier, soon after they had met. They had ridden out as dawn broke over the Rift Valley and Eva had spotted a funny-looking creature about the size of a squat, sturdy, short-legged dog. It had black fur on its belly and lower body and white and pale grey on top, and was snuffling round in the grass like an old man searching for his reading glasses.

‘What is it?’ she had asked, to which Leon replied, ‘It’s a honey badger.’ He told her that this unlikely beast was one of the most ferocious, fearless creatures in Africa. ‘Even the lion gives him a wide berth,’ Leon had said. ‘Interfere with him at your peril.’

He could be talking about himself, Eva had thought. Leon had only been in his mid-twenties then, scraping a living as a safari guide. Now he was just a year shy of forty, the look of boyish eagerness that had once lit his eyes was replaced by the calmer assurance of a mature man in his prime, confident in his prowess as a hunter and fighting man. There was a deep groove between Leon’s brows and lines around his eyes and mouth. With the frustration felt by women through the ages, to whom lines were an unwelcome sign that their youth and beauty were fading, Eva had to admit that on her man they suggested experience and authority and only made him all the more attractive. His body was a shade thicker through the trunk and his waist was not as slender as it had once been, but – another unfairness! – that only made him seem all the stronger and more powerful.

Eva looked around at the other men of the expatriate community gathered in this particular corner of Kenya. Her eyes came to rest on Josslyn Hay, the 25-year-old heir to the Earl of Erroll, the hereditary Lord High Constable of Scotland. He was a tall, strongly built young man and he wore a kilt, as he often did in honour of his heritage, with a red-ochre Somali shawl slung over one shoulder. He was a handsome enough sight, with his swept-back, matinee-idol blond hair. His cool blue eyes looked at the world, and its female inhabitants in particular, with the lazy, heavy-lidded impudence of a predator eyeing its next meal. Hay had seduced half the white women in British East Africa, but Eva was too familiar with his type and too satisfied with her own alpha male to be remotely interested in adding to his conquests. Besides, he was far too young and inexperienced to interest her. As for the rest of the men there, they were a motley crew of aristocrats fleeing the new world of post-war Britain; remittance men putting on airs while praying for the next cheque from home; and adventurers enticed to Africa by the promise of a life they could never hope to match at home.

Leon Courtney, though, was different. His family had lived in Africa for two hundred and fifty years. He spoke Swahili as easily as English, conversed with the local Masai people in their own tongue and had excellent Arabic – an essential tool for a man whose father had founded a trading business that had been born of a single Nile steamer but now stretched from the gold mines of the Transvaal to the cotton fields of Egypt and the oil wells of Mesopotamia. Leon didn’t play games. He didn’t have to. He was man enough exactly as he was.

Yes, Badger, I am lucky, Eva thought. Luckiest of all to love and be loved by you.

Saffron steadied herself at the start of her course. I’ve simply got to beat Percy! she told herself.

It was Percy Toynton’s thirteenth birthday in a week’s time so he only just qualified for the event. Not only was he almost twice as old as Saffron, both he and his horse were far larger and stronger than she and Kipipiri. Percy was not a nice boy, in Saffron’s view. He was boastful and liked to make himself look clever at other children’s expense. Still, he had got round the course without making a mistake. So she absolutely had to match that and then beat him in the jump-off that would follow.

‘Don’t get ahead of yourself,’ Daddy had told her over breakfast that morning. ‘This is a very important lesson in life. If you have a big, difficult job to do, don’t fret about how hard it is. Break it down into smaller, easier jobs. Then steadily do them one by one and you’ll find that in the end you’ve done the thing that seemed so hard. Do you understand?’

Saffron had screwed up her face and twisted her lips from side to side, thinking about what Daddy had said. ‘I think so,’ she’d replied, without much conviction.

‘Well, take a clear round at show jumping. That’s very difficult, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ Saffron nodded.

‘But if you look at a jump, I bet you always think you can get over it.’

‘Always!’ Saffron agreed.

‘Very well then, don’t think about how difficult it is to get a clear round. Think about one easy jump, then another, then another … and when you reach the end, if you jump over all the jumps, why, you’ll have a clear round and it won’t have seemed difficult at all.’

‘Oh, I understand!’ she’d said, enthusiastically.

Now Saffron glanced at the ragged line of her fellow competitors and their parents that ran down one side of the ring, and saw her father. He caught her eye and gave her a jaunty wave, accompanied by one of the broad smiles that always made her feel happy, for they were filled with optimism and confidence. She smiled back and then turned her attention to the first obstacle: a simple pair of crossed white rails forming a shallow X-shape lower in the middle than at the sides. That’s easy! she thought and felt suddenly stronger and more confident. She urged Kipipiri forward and the little mare broke into a trot and then a canter and they passed through the starting gate and headed towards the jumps.

Leon Courtney had made sure not to convey a single iota of the tension he was feeling as Saffron began her round. His heart was bursting with pride. She could have entered the eight-and-under category, but the very idea of going over the baby jumps, the highest of which barely reached Leon’s knee, had appalled her. She had therefore insisted on going up an age group, and to most people that in itself was remarkable. The idea that she might actually win it was fanciful in the extreme. But Leon knew his daughter. She would not see it that way. She would want victory or nothing at all.