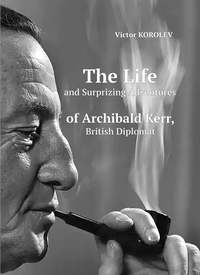

Kitabı oku: «The Life and Surprizing Adventures of Archibald Kerr, British Diplomat», sayfa 2

Bir şeyler ters gitti, lütfen daha sonra tekrar deneyin

5,0

2 puan

₺133,49

Türler ve etiketler

Yaş sınırı:

16+Litres'teki yayın tarihi:

25 mayıs 2020Yazıldığı tarih:

2020Hacim:

211 s. 3 illüstrasyonISBN:

978-5-6043924-5-4Telif hakkı:

Логос