Kitabı oku: «The girl that could not be named Esther», sayfa 4

All this lay hidden from the reader of the Frankfurter Zeitung. Such a reader was told only that another person had demanded German names for German children. It is not clear what the editorial board hoped to do by so basically changing the content and the purport of the article in question as to render it seemingly harmless.

The introductory sentence of the article in The New Folk is striking for another reason. There — and thus in the Frankfurter Zeitung — the subject is a recently released directive of the Reich and Prussian Minister of the Interior, according to which Jews from then on should bear only Jewish given names. Since this sentence appears in the August issue of The New Folk, and on August 11, 1938, the Frankfurter Zeitung already cites this article, the phrase recently released directive can refer only to a directive published shortly before August 1938. But there was no such directive! Not yet. It appeared exactly one week after the article was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, that is, on August 17, 1938. Guidelines on administration appeared on August 18. While writing his article for the August issue, the author must have assumed that the directive would have already come out. Where he got his information is an open question.

The other article, German and Jewish Given Names, had appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung on August 7, 1938, and concerned a decision of the Supreme Court on Civil Matters in Berlin of July 1, 1938, published August 5, 1938. The Private Telegram of the Frankfurter Zeitung column began with these words:

A registrar is not obligated to register a typically Jewish given name for a pure-blood German child. In one sentence, that is the essence of the decision pronounced on July 1 by the Prussian Supreme Court on Civil Matters and published in German Justice.

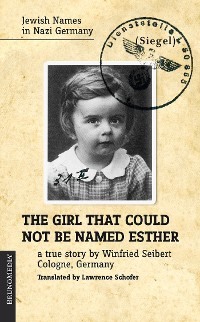

The trial involved the name Josua (Joshua in English), which a forest ranger named Lassen from Marienwerder had intended for his son. The name was rejected by the Supreme Court as typically Jewish. The version published in the professional journals would have been available to the responsible registrar in Gelsenkirchen when he was to decide about the given name of Esther. Pastor Luncke, had he read the Frankfurter Zeitung of August 7, 1938, could not escape the conclusion that in the view of the Supreme Court the name Esther as well would be considered typically Jewish and thus not admissible for German children. Following the reasoning of the Supreme Court as conveyed in the Frankfurter Zeitung, this fate was to be shared by the name Esther with the names Josua, Abraham, Israel, Samuel, Salomon, and Judith. Consequently, the registrar in Gelsenkirchen refused to enter the name Esther in the book of births, since it was a typically Jewish name.

No more talk about senseless, ridiculous, or offensive – typically Jewish was now enough. Typically Jewish as a grounds for refusal was new. That’s why the Josua decision of the Supreme Court merits closer consideration. It must be read under a magnifying glass to understand it depths and its shoals. After all, this decision is one of the two most important decisions on the law of names made by the Supreme Court on Civil Matters in its role as an authoritative court.

The king loved Esther more than all the other women, and she won his grace and favor more than all the virgins. So he set a royal diadem on her head and made her queen instead of Vashti.

Book of Esther, 2:17

Andrea del Castagno c. 1450

Chapter 5

Since 1936 the Prussian Supreme Court in Berlin, along with the Appeals Court in Munich, had been responsible for jurisdiction over all civil administrative matters.54› Reference Its definitive responsibility as court of last appeal went far beyond the authority of its officially defined geographic jurisdiction.55› Reference Civil administrative affairs included the law on names, in which this Court had the final word for more than half of the German state. Its interpretation of the law set precedents, which in turn guided the decisions of the local registrars. A review of the decisions regarding the law on names from this period shows that the Appeals Court in Munich handed down a declining proportion of these decisions, while the lion’s share published in professional journals originated in the Supreme Court. A circumstance that may have played a role in this dominant position was that since the beginning of 1938 the state Senate committee with responsibility for names had among its members a young judge who regularly supplied the Journal of Registry Office Affairs with the current decisions of his Senate. We’ll hear more about him later.

If a registrar were to refuse to register a name, the father could apply to the appropriate district court to require the official to register the name,56› Reference upon which the registrar’s supervisor, that is, the head of the city involved, could file a complaint at the state court level. The law allowed a further appeal of the decision to the State Supreme Court, i. e. from 1936 on, to the State Appeals Court in Munich or to the Prussian Supreme Court for Civil Matters in Berlin.

And so the case of the forest ranger Cuno Josua Lassen from Marienwerder in West Prussia came before the Supreme Court. He had wanted to name his son, born February 16, 1938, with the same name, Cuno Josua. The registry official had refused to register the name Josua [English –

Joshua] on the grounds that this name is of Hebrew origin and has found so little entree into the German language that it can in no way be considered a German name.

Here is where the Decree of April 14, 1937 came into play. The opinion was defensible at the administrative level. Josua was without a doubt a foreign name, and it could hardly be called completely Germanized. The question was only if this decree was so binding on the registrar that he had to refuse it. If one were to go by the wording — basically only German given names are acceptable — then this was a recommendation and not a binding order. So there was still wiggle-room.

That is what Forest Ranger Lassen was counting on when he turned to the District Court. He based his appeal on the fact that Josua is a biblical name, and that the names Cuno Josua had been customary in his family for generations. He was living proof of this custom. He cited two traditions, the biblical tradition and his family tradition. Biblical tradition played no role in the 1937 decree, which distinguished only between German names and foreign names. Family tradition, however, was well accepted as an exception because, as they then said, it served the purpose of the development of clan thinking, if given names are chosen based on names previously used in the clan.

The District Court in Marienwerder ordered the registry official to register Josua as an additional given name beside Cuno. We don’t know the reasoning, but the State Court in Elbing overruled the decision when the city appealed. The grounds can be inferred from the later decision of the Supreme Court:

The name Josua is taken from the Old Testament57› Reference, is of Hebrew origin, and even today sounds Jewish. Assimilation into the German language and incorporation into the German vocabulary, such as has occurred with other biblical names like Hans, Peter, Maria, Ruth, Johannes, Paul, etc., has not happened with the name Josua. In light of the current viewpoint of the National Socialist state, such a given name should not be adopted for a German child. Even what can be considered a legitimate family tradition does not outweigh this conviction.

Here too there were echoes of the 1937 directive. Assimilation into the German language corresponded to the wording completely Germanized in that directive, while the reference to the current viewpoint of the National Socialist state was a freewheeling addition by the State Court. It was intended to make recognizable the legal basis for the refusal of a name unassimilated into the German language, a name with Jewish overtones. We don’t know if the State Court went further in its decision. The question of whether the current viewpoint of the National Socialist state could replace a legal regulation is one that we will follow to the Supreme Court. In its decision of July 1, 1938, the court put out a mighty effort to lay such a foundation, but that decision raised more questions than it answered.

The Supreme Court began its reasoning with a summary sentence cutting to the heart of the matter:

There has been no legal regulation up to this time. In the choice of given names, one must assume that the chosen name must first of all be a name, and it must not offend good morals, state order, or religious feeling.

The court here refers to its own decision of 1931, in which it said:

Therefore, the choice of given names, aside from indecent and offensive names, is basically unlimited. Thus nothing stands in the way of registering given names for children of residents of Germany, not even if they are in a foreign language.

Josua was a name; it did not offend religious feelings; there was nothing blasphemous in this biblical name; it was not indecent or offensive. It remained only to show whether or not this name offended good morals and/or state order.

To this end, these two undefined legal concepts, which in German law had long appeared as a formulaic expression, had to be elaborated for this concrete case.

If one were to understand under state order more than the regulatory framework set up by laws and ordinances, then this concept would encompass the totality of rules, including unwritten ones, which were followed in accordance with the prevailing social and ethical views as an essential prerequisite for people to live together successfully in a society.58› Reference This would not be a blanket formulation if the concept were more precise. The same goes for good morals. 59› Reference The criteria for the legally relevant aspect of morality are the rules of morality taken up by the law and the moral law. 60› Reference

And so these general formulations turned out to be the gateway through which the currents of the day poured in. In the systematically structured building of the Law, these are the open windows through which social changes can enter and become effective. Tempora et mores mutantur – Customs change with the times, as the Latin proverb goes. Of course, changes can be enforced only via a judicial decision.

For a definition of good morals, legislators and legal precedents give little more than hackneyed phrases. The Commentaries on the Civil Law Code speak of standards of propriety of all proper and right-thinking individuals. 61› Reference The Imperial Court supplemented this in 1901 with in the dominant popular consciousness, and in 1912 the Imperial Court described this standard of propriety with in morals, in the ordinarily occurring feeling of the average citizen. Then in 1930 a court spoke of the dominant moral outlook of all law-abiding and moral people and the feeling of propriety of all citizens with an average proper, fair and upright consciousness, and finally in 1936 the National Court [Reichsgericht] based its views on the National Socialist worldview, which is the dominant popular feeling since the radical breakthrough in the government [Hitler‘s assumption of power in 1933]. And so this court equated the dominant national feeling with this worldview,62› Reference and for the first time used the concept of a healthy national feeling — gesundes Volksbewusstsein, 63› Reference which the National Socialist legislators had instituted as early as 1935 in sweeping away the principle of Nulla poena sine lege — No law, no punishment. 64› Reference

The Supreme Court could have made things easy for itself in its decision about the name Josua. With a few sentences it could have deduced from the generally prevailing notion in Germany in 1938 that foreign given names for German children had in the meantime become undesirable, and that the recognition of such a name for a German child, which at an earlier time might have been in order, now was to be seen as an offense against good morals and state order. A test public opinion survey would undoubtedly have supported this result. German names for German children – that was presumably the majority opinion in 1938. Nobody would have criticized the Supreme Court if it had so viewed the case and had so decided.

The next step would then have been to consider the question of whether the given name Josua, which without a doubt was not originally a German name, could be considered as one no longer foreign and thus completely Germanized. The answer would have been an unequivocal NO. Josua sounded just too foreign and was too rarely used to consider it as incorporated into local society. All of that could have been reasoned out with a few sentences which would have harmed nobody outside of those directly involved in the affair. But the Supreme Court did not want to make it so simple. For the Court, a lot more was at stake.

To understand this, we have to follow the Supreme Court step by step, that is to say, sentence by sentence through its reasoning. This is a nasty road, but we have to take the Court at its word, at its every word.

After the appropriate title sentence, there follows a conceptual narrowing, which points out the road to be followed:

We must adhere to the fundamental principle that a German name is to be bestowed upon a German child, that is to say, a name that takes its origin from German history, German legend, or German custom and is accepted as German by the people.

There follows a reference to the Directive of April 14, 1937, which, as we already know, says that in principle only German names are to be given and others are not desirable. Even a sophisticated phrase referring to the situation that a German name is to be bestowed upon a German child can hardly conceal that this is only a wish for German parents to embrace German given names. If German parents in their ignorance fall short by choosing names that in this view are not to be bestowed upon German children, then that is perhaps a regrettable error, but not one that is forbidden. This could only be a guideline to be respected if the requirement for German names for German children should be in line with the viewpoints of state order or good morals. The Supreme Court makes no reference to this however. It simply presumes a fundamental principle, of which until now we know only that it is not compulsory and is nothing more than a recommendation.

Even the words, we must adhere to the fundamental principle, make no sense. With this decision the Court did not want to confirm some good old custom or perhaps to prevent modern deviations; it wished exactly the opposite. With the demand for exclusively German names for German children it was entering virgin territory for the law on names. With one sentence, and with no basis, the not desirable of the ministerial directive had become a not permitted.

With its comment that a German given name is a name that takes its origin from German history, German legend, or German custom and is accepted as German by the people, the Supreme Court presented a definition that incorrectly relied on the Directive of April 14, 1937. In that directive there is no definition of German given names, no word of German history, legend, or custom. Beyond that, it only spoke of names originally of foreign origin but in use in Germany for centuries, which, if completely Germanized, could continue to be used without further hesitation. That was the only item of interest. Josua without a doubt was not a German name, and all well-founded references to German given names and their origins were beside the point.

The next sentence went back to the directive and pointed to another group of names that was admissible, with these words:

Furthermore, other names are possible that stem from a foreign language and foreign historical and philosophical circles, but have been assimilated into the texture of the German language in the course of longterm development to the point where they seem German and people hardly consider them foreign anymore. To this group belong given names like Alexander, Julius, Rose, and Agathe.

The preliminary decision had already been made against foreign given names, even though the Supreme Court had had no objection to such names in 1931. Not one syllable touched on the overturning of this earlier decision, despite express reference to it. If the court had decided to approve only German or Germanized names, this would have been the occasion to quickly make such a decision. With but a few words, the Supreme Court could have decided that the name Josua could not pass for German, that it was still considered foreign by the people, and consequently could not be allowed. Instead, the Supreme Court now developed its own system of names of foreign origin that were hardly considered foreign anymore. While the area laid out with the examples Alexander, Julius, Viktor, Rose, and Agathe was not explained any further, the Supreme Court did go on to distinguish two equivalent groups:

Names of Christian origin, that is, names of persons who had a direct, personal relationship to the founder of the Christian religion and who were mentioned in the New Testament. This involves names primarily of Hebrew origin, like Joseph, Johannes, Matthäus, Matthias, Maria, Elisabeth, Martha,

and

Names of Christian but not Hebrew origin of people who in later Christian history achieved fame, e. g., Thekla, Agnes, Nikolaus, Franziskus.

In the eyes of the court, names from both these groups were generally not considered un-German. It referred in particular to the German variations derived from these names, like Hans, Peter, Paul, etc. If one were to take seriously the stipulation the court itself had set, the only point that mattered was whether or not a specific name of foreign origin — Josua was such a name — had been absorbed into the texture of the German language over the years to the extent that it was no longer (or hardly any longer) considered foreign. Where the name came from, whether there were prominent people of that name in history or literature, was meaningless for the question of whether the name was completely Germanized. The Supreme Court had taken a wrong turn.

In its definition, names of persons who had a direct personal relationship to Jesus and who are named in the New Testament were the ones most likely to no longer be considered foreign. This group undoubtedly included the Disciples of Christ, the later Twelve Apostles, whose names we know from the Gospels. Petrus — Peter — actually was named Simon, and among the Disciples there were as well Simon the Cananaean and Simon the Zealot. Was the name Simon then Germanized and no longer considered foreign? The National Office for Clan Research had at the beginning of 1938 given the Ministry of the Interior a list with typically Jewish names, which were to be made compulsory for German Jewish children in a future regulation. The list included the name Simon. And what about Judas? In Luke there were two Disciples of this name, including not only Judas Iscariot but also another Judas, the son of James.65› Reference Despite a highly direct personal relationship to Jesus, people would certainly have considered these names to be foreign. It seems then that the criterion thought up by the Supreme Court was useless.

Perhaps it will become clearer from the broader reasoning why the Supreme Court went off on this tangent. Here the Court was concerned with the third group of biblical names, which they said required special handling. Now we are getting to the heart of the matter.

Names at issue were those that

are cited in the Old Testament, are of Hebrew origin, and whose bearers have no relationship to Christianity or who have only a distant, indirect relationship to it.

If one grants that the Supreme Court was seeking a solution to the question of which names were no longer considered foreign, then behind this formulation there stood the assumption that the more distant the relationship of the first bearer of an Old Testament name to Christianity, the more likely such a name was to be regarded as un-German. Still, the question remains how proximity to Christianity is to be measured, since the Old Testament and all the people mentioned in it are inevitably part of the Christian tradition.

Without an Old Testament there would be no New Testament; without Jesus, who came from the Jewish tradition, there would be no Christianity. The Court was building for itself here a system based on what seemed to be a spiritual exploration, one which was completely irrelevant for its decision. This wasn’t a matter of the significance of the first bearers of biblical names to Christianity; but rather — according to the court’s own stipulation mark you — it was a matter of the general consensus of the year 1938, that is, how such a name was perceived. Theological argumentation was of no help here.

Asked in another way – in the opinion of the Court, were Old Testament names automatically acceptable without any pre-conditions if their first bearers had a meaningful relationship to Christianity? This group is not even mentioned. Wasn’t the forefather Abraham indispensable for Christianity? And David, to whom Jesus traced his lineage? Could there have been any closer relationship than this? Where were these names in the new system of the Supreme Court?

The feeble nature of this argument is clear if you look at the further differentiation that the Court draws within this group of Old Testament names, whose first bearers stand at best in a distant, indirect relationship to Christendom. It writes:

Here too there are names which by usage over time have infiltrated into the German language to the point that they are no longer considered un-German, and as a result innocent German children are given such names as Eva and Ruth.

It is true that these names were used in Germany for centuries and therefore not seen as foreign. It was absurd to rank Eva, German for Eve, the original mother, among those in a distant relationship to Christianity. Christian belief, with its roots reaching deep into the Old Testament, would be inconceivable without Adam and Eve! And if the name Eve is brought up, why not Adam? Were there special reasons that just these two female names were brought up as innocent? For the name Eve, or Eva, the reasoning is obvious. For the beautiful name Ruth, the judges of the Court would include some explanatory material in the Esther decision. But enough about the innocent exceptions. The Supreme Court continues:

A different judgment must be made regarding names that have a particularly Jewish sound, which have not gained entry into the German vocabulary, and in the eyes of the general German public are considered ‘typically Jewish.’

It sounds like these three elements are meant to be cumulative, but it just wasn’t so. Sticking with the pronouncement of the Supreme Court given above, we see that it was important if a name had gained entrance into the German vocabulary so that it was not considered foreign. Everything else was nothing but unnecessary detail. It couldn’t be denied that names considered typically Jewish were in this sense not completely Germanized. That applied as well to names that people considered typically American or typically Italian. To create a sub-group labeled typically Jewish was not something that necessarily flowed from the grounds of the decision. Such detours in legal reasoning were superfluous, and according to the rules of the legal art were completely out of place. The judges could have long before achieved the desired result of refusing the name Josua, but the Court saw it differently. It went way beyond the topic at hand: it was concerned with much more, as its reasoning showed. It was looking for a greatly emphasized form of foreign and considered foreign, a form that would allow no loopholes. Without any technical legal need, on ideological grounds alone, and with unabashed adoption of Nazi phraseology, the Prussian Supreme Court on Civil Matters singled out a group of names as typically Jewish.

For its definition, it brought up a formula that had come into use and which for some time could be read in the guidelines for dealing with applications to change family names. The formula could certainly be applied to given names as well:

The names that are considered Jewish are determined by general public opinion.66› Reference

The Supreme Court did not go any further than that, but instead put its notions in the place of general public opinion and pronounced in a manner that brooked no opposition:

Such names are those like Abraham, Israel, Samuel, Salomon, Judith, and Esther.

There wasn’t much to say about the four men’s names, but Judith and Esther were less clear. The State Supreme Court in Munich, which had a level of jurisdiction in naming matters equal to that of the Prussian Supreme Court, had dealt with the name Judith in a decision of December 22, 1937, without any reference to this name’s being anything out of the ordinary. That did not faze the Prussian Supreme Court one bit. With a casual reference, applications concerning the names Judith and Esther were dispatched with, and one could hardly expect that the court would deviate from the line that it had laid down on July 1, 1938, should one of these names come before it. In the meantime, neither of these names was at issue, since Esther Luncke had not even been born yet.

The Court now made a short digression by noting that German parents had nonetheless sometimes given their children such typically Jewish names, especially in Reformed Protestant parishes such as those in and around Wuppertal, an area where the Lunckes happened to live. It conceded that the choice of such typically Jewish given names often fit the views of an earlier Germany, but then without apparent basis it dropped this theme of tradition in order to switch over to the biblical story of Joshua. If it was a matter of how the name Joshua (Josua in German) was seen by the public, this foray into the Old Testament was unnecessary. Even for the question of whether it was received by the public as typically Jewish, the answer could not be found in the Bible. The efforts at Bible commentary by the Supreme Court were absurd.

The first person to bear this name played a great role in the history of the Jewish people since he became the leader of the people after the death of Moses and conquered the land of Canaan for his people.

That’s the way it came out in the Bible. A victorious military leader, the one who smote the Amalekites right after the Exodus from Egypt at the place called Refidim, conqueror of the land of Canaan, destroyer of the walls of Jericho, a Jewish hero whose prayer in the battle against the Amorites had caused the sun over Gibeon to stand still. If not for his Jewish connection, he would have fit right into the Valhalla of conquering heroes. Since the name of a Jewish war hero in all likelihood was seen as typically Jewish, the decision could have quickly come to an end here. The Supreme Court however went down another irritating detour:

It cannot be ascertained that the name Josua has attained such a great significance for the Christian religion, let alone for the German nation, that on these grounds it could be allowed as the choice of a given name. People bearing the name Josua are not generally known as having stood out in German history, economics, or philosophy.

What was that supposed to mean? The name Josua was not Germanized. The Court had already labeled it as typically Jewish. Did it now want to take it all back and allow this name as an exception if there had been great people with the name Josua in German history, economics, or philosophy? Was it a matter of a name being well received by the German people in the year 1938 or wasn’t it? Could the great significance of some Josua for the Christian religion or for the German people justify allowing a typically Jewish and un-German name?

The Supreme Court got out of this sticky situation with the soothing recognition that such great men were not generally recognized; it could find only Josua Stegmann, composer of the church hymn Abide, O Dearest Jesus, Among Us with Thy Grace. In this case it turned out — luckily for the Supreme Court, one might add — that it was a matter of not being a person endeared to the entire German people.

All of this leads to the very heart of the reasoning in the decision, since the name Josua had by now become a secondary matter. Here is the way the Court formulated its basic declaration:

The question of whether one can allow names generally regarded as ‘typically Jewish’ to be given to German children must in today‘s world be answered from completely new and independent points of view. What is crucial in this matter is whether such given names are compatible with the National Socialist conception of the People and the State, as this conception has been put into practice since the take-over of power and has been increasingly spread everywhere. From this point of view, the admissibility of such names must absolutely be denied.

The National Socialist conception of the People and the State was thus to form the obligatory standard, even though the Court admitted that this standard did not yet prevail everywhere. But what are these completely new and independent points of view which, in the Supreme Court’s opinion, make it impossible to give a child a biblical name like Josua in today’s world? The Court pulled no punches on this point:

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.