Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

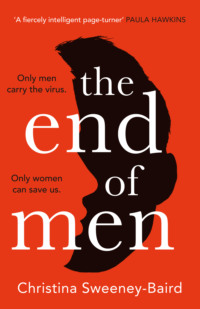

Kitabı oku: «The End of Men», sayfa 2

OUTBREAK

Amanda

Glasgow, United Kingdom Day 1

November is always busy but this is ridiculous. The area around Gartnavel has never shown its divisions more apparently. The ice-induced falls and chesty coughs of Glasgow’s polished, middle-class West End residents appear in A&E in a flurry of expensive highlights, knowledge of different kinds of antibiotics and clipped accents which make clear they want their parents and grandparents to be seen now. The other side of this tale of two cities is liver cirrhosis, chronic poverty and the unglamorous side effects of a life of smoking.

‘It’s another SLS,’ Kirsty, an excellent young nurse, says gaily as she swings past me, unceremoniously plonking a chart into my arms. Shit Life Syndrome. Doctor speak for, ‘There’s actually nothing wrong with you. You’re just really sad because your life is really, really hard and there’s nothing I can do about that.’ I used to try and help, little naive waif that I was. What if they have nobody else? I would think desperately to myself, as I phoned social services seven times in one night until they stopped answering me. As a consultant, my approach is a bit different.

‘Why am I seeing them then?’ I ask. This is a waste of my time – a classic, shit junior doctor task if there ever was one.

‘They’ve specifically asked to see a consultant and won’t talk to anyone else.’ Ah. Unfair as it is, being loud, insistent and generally a pain in the arse will often get you better care in hospital. Not because we respect those kinds of antics. We just want to get you out the door.

I walk into the cubicle, the curtain providing a thin semblance of privacy. ‘What can I do for you?’ I ask in my special chirpy but curt voice that I save for the healthy in my overcrowded, underfunded A&E department.

‘He’s naw well,’ the pasty woman to my left growls pointing at a child who, while bored, looks to be in rude health.

‘What appears to be the problem?’ I ask sitting in front of him. From his notes I can see his vitals are all normal. He doesn’t even have a temperature. He’s fine.

‘He keeps sleepin’ til late an’ he’s got a cough.’ The child has literally not made a sound.

A few harmless questions later and all is revealed. He’s going through a growth spurt and tried a cheeky cigarette on the way home from school with a fellow wayward friend. Somebody call Sherlock, I have a gift.

As I’m waving the sheepish boy and his mother out the door, I hear the ring of the trauma phone. I take the call. A two-month-old child, suspected sepsis. On the way in.

There’s an adrenaline rush when the phone rings for an incoming trauma that even after twenty years as a doctor, I’m never immune to. After forty-five minutes of breathless work stabilising the baby, he’s being whisked upstairs to the ICU. There’s barely a moment to turn around and think before another trauma comes in. This one’s more routine. A road-traffic collision has resulted in some nasty gashes and suspected internal bleeding. That one’s off upstairs to a CT scan within twenty minutes. I’m washing my hands and trying to remember what time my son’s parents’ evening starts when one of my first-year junior doctors grabs me.

She’s babbling about a patient crashing who had been fine and now he’s not fine and help. She’s a mess. I’ve seen it so many times before. She’s only been on the ward for ten weeks and she has a patient deteriorating and she’s panicking. I know I should be respectful and aware of the fact that she’s only a junior doctor and we all have to learn but really, it’s just annoying. I can understand a lack of knowledge and I can tolerate the mistakes made due to exhaustion. But sheer panic in an A&E department is as useful as a papier mâché boat with a trapdoor. It sounds unkind even as I think it but my immediate thought is, she’s never going to be an A&E doctor. If you can’t keep your head screwed on when a patient’s crashing then an area of medicine devoted to emergencies is not for you.

I run with her back to the cubicle. The patient’s wife is standing next to the bed with him, crying. I practically hiss at Fiona to get him into Resus and ask as quietly, and furiously, as possible why he isn’t there already. Even a cursory look at this man and his vitals shows that he’s seriously unwell. Jesus, you don’t even need to look at him. Every machine is beeping in persistent, whining concern.

Fiona says he’s had the flu, and he was fine when he arrived, just fine! She gave him fluids and paracetamol and had clearly hoped that he’d go away after a while, having been convinced that it was in fact, just the flu and nothing more.

By this point the patient is dying. His breathing is laboured with the shallow pant of a body not coping with the basic requirements of taking in air. His skin has the grey pallor of someone whose bodily systems are shutting down and his temperature is climbing higher and higher. There are now seven members of staff surrounding him. Matron is taking his temperature at two-minute intervals and announcing with barely disguised disbelief that it’s climbing this quickly. We strip him and surround him with ice and cold towels. I examine his entire body looking for a wound, an insect bite, a shaving cut, a scratch. Anything that could be causing sepsis. There’s nothing. No rash so meningitis is unlikely. By this point I’m starting to think he’s past the point of no return. There’s not a huge amount you can do once the organs start shutting down. We catheterise him, give him fluids and oxygen. We pump him full of massive amounts of antibiotics and antivirals to start fighting whatever it is that’s burning him up, we give him steroids for his breathing, we do everything we can. We take bloods to screen for infection and if he can at least survive until we get those back, we can tailor the antibiotics or antivirals we’re giving him but now his kidneys are shutting down. There’s zero urine output – the bag under the bed from the catheter is flapping in the air, depressingly empty. I often tell my friends when they half-jokingly ask me if they’re dying, if you still need to pee, you’re fine.

As I stand back and watch the scene unfolding in front of me, I keep my face arranged in an expression of grave calm. He’s a handsome lad. Dark hair, stubble across his chin, he looks kind. His wife keeps getting in the way, crying and crying, inconsolable. She can see the writing on the wall. We all can. She occasionally shouts at us to do more but there’s nothing more we can do but wait and hope that by some miracle his body will turn itself around. Three hours after he arrived in A&E, the machine we’ve all been waiting for begins its long shriek. His heart has stopped. In an odd way it’s a relief. The tension in the room has dissipated. Finally, we can all do something. Matron starts with compressions. I order for the epinephrine to be given. We shock him once, twice, three times. A nurse has his wife, mute now with shock, in the corner of Resus keeping her upright and away from the bed. The violence of an electric shock is not something a loved one should see if it can be helped. In the effort to bring someone back from death we pulverise them, shock them, try to fight their hearts back into a grudging rhythm.

It’s not working but we all knew this would be the outcome. This is a man whose body has been ravaged by something, but we don’t know what yet. Our arms tire. Matron looks at me questioningly with the paddles in her hands. I shake my head. We have done everything we can and should. To keep going now would be to inflict unnecessary torture on the body of a dead man. After fifty-two minutes I make the order. ‘Everybody stop. Enough.’

‘Time of death, 12.34 p.m., 3 November 2025.’ I leave one of my senior registrars to complete the admin that comes with death and comfort this poor man’s grieving widow. Only a matter of minutes ago she was a wife.

Fiona, my panicking junior doctor, is distraught. It’s the first young patient she’s lost in the department and it’s different when they’re young. It’s never easy to lose a patient but when someone’s eighty-five and they’ve had a long life and suffered a stroke or a massive heart attack, you’re sad but there’s a sense that this is part of life. Death comes for us all and you’ve had a good innings. Godspeed and see you on the other side.

But when someone young dies it’s because something has gone seriously wrong and we have been unable to fix it. The patient was called Fraser McAlpine. His wife is sobbing over and over again that it was just the flu.

I take Fraser’s chart and lead Fiona to the staff room. I sit her down so she can recover from the stress and go over what happened and why. It’s a technique I learnt from a consultant when I was training in Edinburgh. When you’ve lost a patient, you go through the chart straight away from start to finish, step by step. What did you do, when did you do it, why did you do it, how did you do it? Normally it makes the junior doctor realise that they did everything right and it was completely beyond their control. And if they did something wrong, it provides a learning experience. It’s a win-win.

We go through the chart with a fine-tooth comb. Fraser arrived at A&E at 8.39 a.m., so far so normal. He was seen by a triage nurse at 9.02 a.m. who deemed him to be low-urgency based on him appearing to have the flu. He only had a slightly elevated temperature and was breathing normally. He complained of feeling lethargic and having a headache. He saw Fiona at 10.15 a.m. who put him on fluids and gave him paracetamol. She offered to run a blood test to see if he had a bacterial infection or a virus, and to treat him accordingly. He was put on the list for the nurse to take blood. His temperature at 10.15 a.m. was 38.8 degrees. That’s barely elevated. Even a new parent with a six-week-old baby wouldn’t lose sleep over that.

Thirty minutes later, at 10.45 a.m., three quarters of an hour before his heart stopped, his temperature was 42 degrees. At that point you’re basically dead. That’s when Fiona came to get me. My blood runs cold. His body went from being normal to near dead in under an hour.

I can see Fiona relaxing as we review his notes. I haven’t mentioned a mistake she made and I’m clearly unnerved. This is not a simple case of junior doctor error. This is horrifying. This wasn’t flu and it doesn’t appear to be sepsis. He was a healthy young man. People drop dead sometimes, even young healthy people. But normally it’s clear what has gone wrong.

Then I see something that causes a wave of nausea to roll through my stomach. He was in the hospital two days ago. My immediate thought is that we must have missed something. One of my team, my doctors or nurses, must have missed something that caused this man to lose his life. I read the notes – he was in with a sprained ankle after a rugby match.

Death is not a side effect of X-raying and icing a sprained ankle.

Then the thought of MRSA pings itself in to my brain. It’s one of the deep fears of any doctor. But this … I don’t know. I haven’t seen an MRSA case before, thank God. But this doesn’t match up.

I’m poring over the notes, trying to find something, anything that would explain what happened. There’s a jagged edge to a memory. Something is nagging at me but I can’t quite bring it to the front of my mind. What is it? It’s not from yesterday. Maybe the day before? It dawns on me. A patient I treated two days ago. An older man, sixty-two, who was flown down from the Isle of Bute. He was gravely ill when he arrived. They’d intubated him on the helicopter. Kidneys had packed up. I wasn’t entirely sure why they had bothered moving him but the paramedic seemed pretty flustered and said, ‘He wasn’t this bad when we picked him up. His temperature has shot up.’ I didn’t think much of it at the time. Sick person’s temperature goes up. It’s not a huge surprise.

He had died about quarter of an hour after arriving. We had done the same thing as we did with Fraser McAlpine – we took bloods to identify what bacteria or virus was attacking the patient. We never followed up on the results though because he died. That was something for the morgue to look at. I check the bed numbers. They weren’t even close. Patients with sprained ankles don’t go into Resus. Then I check the staff who treated the man from Bute. I was the consultant who treated him along with a junior, Ross. One of the nurses, though, was the same. Kirsty treated the man from Bute and Fraser McAlpine.

Please God let Kirsty be a murderer because that would be so much less stressful than this being a contagious infection or a hygiene problem. No, what am I thinking? Murders involve a lot of paperwork.

I can feel the anxiety rising. It’s not the deaths – I’m used to those. It’s the uncertainty. The thing I like most about medicine is the certainty. There are plans and systems, lists and protocols. There are autopsies and inquests. No question is left unanswered. I try to remember how bad things were in my third year at university after Mum died. It’s like exposure therapy I do in my brain. I survived that so I can survive this. I survived panic attacks so if I have one now, I will survive it. I thought I was going to die then but I didn’t. Just because I think I might die now doesn’t mean I will. I didn’t know if I could be a doctor then but I am a doctor now. Be wary of that little voice that tries to twist one scary thing into a spiral of despair.

Do not panic, Amanda. This is just my anxiety talking. Two patients are not an outbreak of an antibiotic-resistant infection. Two patients are not a pandemic. Two patients don’t even comprise a pattern.

Fiona says she has to go. I stare at her blankly, unsure how long we’ve been sitting here. It’s OK, you can take a few minutes, I reassure her. Losing a patient is a lot to deal with. She says that she can’t, because someone’s called in sick. ‘Ross isn’t feeling well so we’re down a doctor.’

In a split second I do something that’s completely insane. If my husband was there, he would say that I need to book in to see my psychotherapist and that my anxiety has gotten completely out of control. But he’s not and I don’t because what if? My mum always told me to trust my gut and my gut is telling me this is a fucking disaster. I can feel the weight of the knowledge on my chest. I need to tell other people. I need to do things and not just worry in silence.

I go back out to the ward. I tell Matron to ask all the patients in the department if they were in A&E two days previously. She just looks at me disapprovingly and I don’t have the time to have a discussion with her so I move on to the waiting room. I ask who was here two days ago and two men stand up. One man just raises his arm. He’s paler than the other two. I get him on a stretcher. My heart is starting to do the clenching thing it does when I’m getting a panic attack but there’s actually a reason for the panic. This has never happened before. It’s always been a panic attack because I was panicking about nothing, it’s not meant to be legitimate panic. I want to cry, slump down in one of the staff room chairs and leave someone else to deal with whatever this is.

They all have flu-like symptoms. Either they or their wives are concerned it’s something sinister like sepsis – there was a sepsis campaign put out by the Government in October. It’s saved around twenty lives in this hospital alone and has also single-handedly increased waiting times. Everyone and their mother are convinced they have sepsis.

I want to tell these men that actually I think this might be a lot worse than sepsis, ten times more terrifying than one of the nation’s biggest killers, but I don’t. I stay quiet and determined and outwardly calm. No one dares to question what I’m doing until I chuck everyone out of the Minor Injuries Unit and place the suspected infection patients in there. One of the nurses starts spluttering at me but I just tell her to go to Resus. I can’t explain things right now, there’s no time. Matron has done as I asked and found two patients who were in A&E two days ago and are now back. I have three from the waiting room. That makes five. Fraser McAlpine makes six. The man from the Isle of Bute makes seven. This isn’t a coincidence.

Fiona bursts through the doors of the Unit. ‘Ross has been brought in by ambulance.’

Eight.

It’s not my anxiety, I know that now. With freezing fingers, I phone my husband.

‘There’s an infection. It’s really bad.’

‘Wait, what? What kind? MRSA?’

‘No, something I’ve not seen before. It’s spreading too fast. You have to go home. Now.’

‘Are you sure it’s not your anxiety talk—’

‘Fuck. Off. I have eight patients dying in a row lined up like we’re in World War Fucking Two. They’re all men, I don’t know if that means anything yet but it’s not a good sign. Go home. I swear to God if you don’t claim you’ve just thrown up and go home I will divorce you.’

I’m hysterical. I have never threatened to leave my lovely, supportive, oncologist husband before. I never imagined anything could drive me to such a threat. But I never imagined this.

‘Go home. Touch no one, speak to no one, just go. Pick up the boys on your way home. Get them to come out to you. Don’t go into the school. Please go get them.’ I’m begging now. Will agrees. I don’t know if he’s terrified of me or for me. I don’t care. He just has to be home safe with our sons. I punch out a text to my boys telling them their dad is on his way to pick them up and they’re to go outside and wait for him. I’ll write whatever note they need. I’ll say anything.

I vaguely know someone who works at Health Protection Scotland. We were at university together and now she’s a deputy director there. She’s always been a bit snippy but I don’t care. I need her to listen to me. I call her and try to sound calm as I speak to the switchboard. When I tell her everything in a rush she keeps making small noises as though she wants to get off the phone. She doesn’t sound worried but also, it seems like she thinks she’s seen this all before. She’s not been a doctor for over ten years but somehow it sounds like she just doesn’t trust me. Maybe the urgency isn’t translating when I explain. It’s so clear to me but it sounds so minor – eight people are sick, OK, we’ll see what happens and we’ll look into it. I put everything down in an email as well and say that, at the very least, they need to send someone to look into it, just in case. I sit down by one of the patients and check his pulse. It is 45. He will die soon. They all will. Breathe, Amanda. The cavalry will charge in soon. I won’t have to deal with all of this on my own. There will be someone I can hand the reins over to. Someone qualified who wears a hazmat suit for a living will come and make everything better and let me go home and forget that this ever happened.

The doors of the Minor Injury Unit swing open. It’s Matron.

‘There’s four more just arrived in ambulances. Two were here two days ago, and the other two were here yesterday. I don’t know what to do.’

My worst nightmare is coming true.

Email from Amanda Maclean (amanda.maclean@nhs.net) to Leah Spicer (l.spicer@healthprotectionscotland.org) 6.42 p.m. 3 November 2025

Leah,

Found your email online. Realised that you forgot to give it to me on the phone after you said to email you. I’ve just arrived home from my shift. When I left there were nineteen live patients in A&E all showing symptoms of what I think is a virus (antibiotics made no difference although obviously need pathology to confirm what’s going on. Is that easier for your lab to do over at HPS or is it quicker for us to just crack on here at Gartnavel?) Of the twenty-six I think we’ve seen so far, five died before I left the hospital. One man, the first I saw, from the Isle of Bute two days ago. Fraser McAlpine this afternoon. Three other men died quickly after coming in including one of my junior doctors, Ross.

They’re all men. Too small a sample size so far obviously but I’ve never seen that before. Maybe men are more vulnerable to it? Can we have a call to discuss all of this please, also maybe loop someone more senior in? This is very bad, Leah. You need to understand how quickly the disease affects them. They go from having normal flu symptoms and feeling quite unwell to being dead with a temperature of over 43 degrees in a few hours.

Please get back to me as soon as you can.

Amanda

Email from Amanda Maclean (amanda.maclean@nhs.net) to Leah Spicer (l.spicer@healthprotectionscotland.org) 6.48 p.m. 3 November 2025

Leah, there was a baby as well, I just realised. We thought it was sepsis. He was in before Fraser McAlpine. He was only two months old. I thought he was stable when we sent him up to the Paediatric ICU but I just called them and he died a few minutes after they wheeled him out of the lift. He was here a few days ago, being treated in A&E.

That makes twenty-seven I saw today. Six deaths. Oldest aged 62. Youngest aged two months.

Amanda

FW: Email from Amanda Maclean (amanda.maclean@nhs.net) to Leah Spicer (l.spicer@healthprotectionscotland.org) 6.48 p.m. 3 November 2025. FW to Raymond McNab (r.mcnab@healthprotectionscotland.org) 10.30 a.m. 4 November 2025

Ray,

See below two emails from a woman I went to Uni with. She’s a consultant at Gartnavel. I think she’s mistaking a bad case of the flu (it’s November after all …) with ensuing sepsis/likely death from other, complicating factors for something more serious. There’s been no other reports of anything on the Category 1 list so I think we’re safe on the SARS /MRSA/Ebola front.

Between you and me, she had a breakdown at university. Completely cracked up and had to take a year out. I think one of her parents died or something? Anyway, she’s quite fragile. I intend to send a holding email advising good infection-control practice and to get in touch if anything further. Flag if you disagree.

Thanks,

Leah

Email from Raymond McNab (r.mcnab@healthprotectionscotland) to Leah Spicer (l.spicer@healthprotectionscotland.org) 10.42 a.m. 4 November 2025

Thanks Leah.

By the sounds of it, a stark raving lunatic who’s trying to waste the limited resources and time of this institution. Not to mention my patience. Ignore please.

Ray

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.