Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

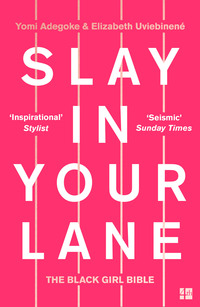

Kitabı oku: «Slay In Your Lane», sayfa 3

And positive changes are happening. Natasha Codiroli finds that female students of mixed ethnicity and Black Caribbean origin are more likely to study STEM A-levels than white female students.11 Indeed, black girls are the only ethnic group that outnumbers their male peers in STEM A-levels.12 STEM is important in driving innovation and is the fastest-growing sector in the UK. There’s never been a better time to encourage young girls into this industry. Role models like Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock understand the need to be visible to school children, and outreach projects are becoming increasingly important in encouraging more black women into all sorts of industries.

Malorie agrees: ‘So, as far as representation is concerned, I think it is absolutely vital, because if I hadn’t read those books, it still wouldn’t be in my head that I could be a writer because I’d never seen any! I remember, for example, when I first started writing, and I wrote a book called Whizziwig, and it was on CITV (Children’s ITV) for a while. I remember going into a school – and this was really instructive to me in terms of representation, because I went into a school in Wandsworth – and I’d say about a third of the pupils were black, or children of colour, and two-thirds were white. I remember that I was talking about Whizziwig, and the idea, and it was on TV and a number of them had watched it, and a black boy put his hand up and he said, “Excuse me, so, Whizziwig was on the television and then you wrote it?” And I said, “No, I wrote it, and then it was on the television.” He said, “But, it was someone else who did it, and then you did it?” And I said, “No, it was my idea and then I wrote the book and then it was made into a TV programme.” And he asked me about five or six questions, all on the same theme, and I was like, “No, I wrote it.” I know exactly what you’re thinking, and I just thought, I loved it, because I was sitting with a sort of smile inside, thinking, I want you to look at me and think, hell, she ain’t all that, so if she can do it, I can do it! And that’s what it was, “You did it? You wrote it?” And I thought, that’s exactly the point! And so I just love that, and that’s why, especially to begin with, sometimes it was two or three school visits a week, and I got out there, oh my God, and I was up and down the country and I made sure I got out there to show, not just children of colour, but all children, that writers can be diverse, that I was a writer. Here I was as a black woman and a writer!’

Similarly, in 2017, Yomi and I were invited by London’s Southbank to mentor young girls between the ages of 11 and 16 for the International Day of the Girl festival. It took me back to my school years and the fear of not knowing what was ahead of me past GCSE results day. Unlike when I was growing up, these girls seemed more confident about what they wanted to do, and asked us interesting questions about our careers and why we made the decisions we did. They didn’t seem lost like I did at their age and that filled me with great hope that things seem to be slowly but surely improving.

In summary, we’ve spoken about the need for an increase in black teachers, the need to tackle the bias held in some pockets of teaching staff through training and accountability, and that parents also need to better understand the school system so they can best support their children in the face of these obstacles. The general feeling of being lost that I experienced throughout school, and especially over that summer as I waited for my GCSEs, came from a lack of confidence in myself that originated in the school system. Changes are slowly happening, but we need to do more to raise the self-esteem of young black girls, so that they know that the sky is indeed the limit, and to actively give them the tools to help them realise their ambitions.

Black Faces in White Spaces

YOMI

.....................................................

‘Lol my sisters oyinbo flatmates threw her yam in the bin cause they thought it was a tree log’

@ToluDk

.....................................................

When I learned I had got a place at Warwick University, I burst into tears. Not tears of joy, mind you: tears of fear. Aged 18, I had flat-out refused to apply to Oxford or Cambridge, my stomach churning at the stories of elitism, racism and all other kinds of ‘isms’ I wasn’t sure I would be able to handle on top of a dissertation. I thought I would much rather learn about those things in a history course than opt into being on the receiving end of them, thank you very much. So instead I applied to SOAS, a very good London-based uni (which even taught Yoruba) as well as Warwick, to please my league-table-obsessed parents. Once I was offered my place, I was ‘advised’ (read ‘ordered’) to go to Warwick by them; it was a decision for which I’m now thankful, but at the time it felt like a form of punishment. I was absolutely petrified I would end up being the only black girl within a 400-mile radius. Even the term ‘Russell Group’ was offputting: it sounded to me like a band of 60-plus cigar-smoking ‘Russells’ for whom fox hunting and racial ‘horseplay’ was an enjoyable pastime. It didn’t exactly scream ‘inclusion’. Of course, when I got there, I realised I wasn’t the only black girl. There weren’t many of us by any measure, but there were enough of us to warrant a populous and popular annual African-Caribbean Society (ACS) ball – and even its Nigerian equivalent.

University was one of the greatest times of my life, but it wasn’t without its challenges. If you are on your way to uni or are considering going there in the future, you will no doubt have already been given lots of advice from websites, teachers and those who have already graduated: don’t leave your dissertation to the last minute; label your food in the shared fridge; rinse the Freshers’ Fair for as many free highlighters and notebooks as you can; always accept the Domino’s vouchers – you will need them. But often one very important topic is left off this generic list of well-meaning wisdom, and that’s how to deal with racism. And when I say racism, I don’t just mean blackface Bob Marley costumes at every conceivable event (there will always be one). As I’ll come back to, statistics show that, like the police force, the health service and the workplace, university is a space where racism is embedded – beginning with the application process and continuing right up to graduation. From often alienating curricula to downright ignorance from flatmates, uni can be intimidating for any student, but this is especially so when you’re black and female.

.....................................................

‘We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto.’

.....................................................

For many black students, university will be their first time living away from home and also often their first time living in a predominantly white area or environment. The beauty of university is that it often thrusts you into the midst of people who are vastly different from yourself, broadening your mind in the process. But this can also sometimes leave you feeling seriously homesick, isolated and generally disconnected.

Little recognition is given to the culture shock experienced by many students coming from predominantly ethnic areas. Maggi cubes become as rare as precious minerals, and weaves often stay on far longer than you’re used to, pretty much growing right off your head for want of a nearby hairdresser. People ask questions you may not be used to answering; for some students you’ll be the very first, real-life, 3D black person they’ve ever met and they will have endless questions about your apparently baffling existence – which has been taking place just two hours down the M40 for the past 18 years – questions which, by the way, you are under no obligation to answer.

When I went to university, my fear that I would be the only black kid on campus wasn’t quite realised, but on the other hand, Warwick wasn’t exactly Croydon in terms of diversity. It is normal for freshers to struggle initially with making friends, but by the end of week one, when one of my first conversations had been with someone who told me he believed there was ‘Me black’ and ‘Rihanna/Beyoncé black’, I had already decided I wouldn’t be spending much time at my halls or with my flatmates. Instead I found solace in the halls a stone’s throw away from me, which housed about half of the uni’s black female intake (again, this wasn’t much). But in those halls I soon found myself a best friend, a boyfriend and a community. Together we searched for hair shops and discovered the clubs that played black music (as much of a banger as The Killers’ ‘Mr Brightside’ was, we heard it more times during the entirety of our nights out than we did anything remotely ‘ethnic’). ‘Black music’ was relegated to a Thursday night and primarily consisted of Sean Paul’s discography.

We swapped eye-roll-worthy anecdotes on microaggressions and lamented the lack of available seasoning in our nearest supermarket. And the best friend I made? I could never have foreseen that eight years, several, several hours of phone calls and even more nights out later, we’d be co-writing a book together. Uni can really be the making of you, even if you don’t always realise it at the time.

Dr Nicola Rollock went to university many years before me and it’s interesting how similar her experience was:

‘I think there were quite a lot of things I took for granted growing up in South-West London, even though I went to this mainly white and very middle-class school. Going to find a black hairdresser’s or Black Caribbean food was normal. Brixton was down the road, Tooting … it was completely normal. I didn’t have to go out of my way to find these things, yet going to Liverpool in the early 90s – and remember this was before it was the European Capital of Culture – was a real challenge, and at 18 I didn’t actually know that I needed those things in my life. I didn’t know they were important to me because I’d really taken them for granted. Even going out was a challenge, in terms of the kind of music I was listening to as a young woman. I had to go out of my way to find venues that would play music I was interested in; there was something called “Wild Life” that happened once a month that played R&B, soul and hip hop – this was once a month at university. So we – me and the few other black girls – ended up befriending black local Liverpudlians and going to “blues”, as they were called, or “shebeens”,13 outside of the university context, because we were really hungry for and looking for places where our culture and identity was recognised and we could just relax.

‘I remember with “Wild Life” we went to enjoy the music, and it felt like some of our counterparts went to drink, and again this was something I wasn’t used to; I didn’t grow up in a house where our parents would say “Go and have a drink,” or, “Here’s some money, go down to the pub.” I didn’t step into a pub until university, and even then I remember saying, “But I’m not thirsty!” Which completely misses the point of going to the pub, as it’s not only about that, it’s about connecting and sitting down and a place to meet, but for me it was just outside of my cultural frame of reference. So I found, in terms of food, music, hair – because my hair was relaxed and straightened at the time – finding a space in which I could be myself and be with others was a deep, deep challenge, so I felt very, very isolated. Then there were the things that many students experience, such as not having any money. I ended up needing to work as well as study … I just found it incredibly difficult and isolating. I would get the train back from Lime Street to London and I would come via Brixton (this was before Brixton was gentrified) and I would walk up the steps at Brixton station and literally, quite literally, exhale, because foods were there, black hair shops were there, my culture and identity was all around me. It was as if I had arrived home.’

.....................................................

‘Ah, the racially insensitive party. A mainstay of primarily white institutions since time immemorial.’

Dear White People

.....................................................

For me and my group at uni, our friendship was a wonderful buffer between us and a lot of things that didn’t have nearly the effect on us as they might have done, had we not had each other. For instance, there was the time the cheerleading club decided to give its annual ‘slave auction’ (which in itself was a problem) a Django Unchained theme. Or when a Snapchat picture was uploaded to one of our university community pages on Facebook featuring a black man wrapped in a net with the caption, ‘I caught me a nigger!’ And let’s not even start on the Stockholm syndrome of other black students who would tell the predominantly black women who kicked up a fuss to ‘chill out’.

And the black face. My gosh, the black face.

Microaggressions (defined as a statement, action, or incident regarded as an instance of indirect, subtle or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalised group) can range from a flatmate throwing out your plantain because they think they’re rotten bananas, all the way to outright flagrant slurs. And in recent years, the racism that was once only whispered about among students has become a talking point on and off campus. Universities put to bed the dangerous myth that racism is the preserve of the ‘uneducated’ and ‘ignorant’ – in fact, it is often those in power who are the ones perpetuating it. Universities are, at times, so racist that they make headlines. The country gasped at the story of a black first-year student at my old university who had found the words ‘monkey’ and ‘nigga’ written on a bunch of bananas she had stored in her shared kitchen. Many black students tutted and sighed, not in surprise but in recognition.

Sometimes the racism is more subtle and underhand, as Afua Hirsch, a barrister, award-winning journalist and author, experienced at Oxford:

‘People always asked for weed, especially when I was with my friends, especially my male friends. They would just assume that they were local drug dealers. And it was always those really posh boys. In their brain, the only function of black men is to buy drugs from. That was one of the most infuriating and offensive things. Or you’d arrive at a party and they’d just assume that you were the local dealers showing up to supply. I hated that, I really hated that.’

A more ‘in-your-black-face’ form of racism is, well, black face. It was a costume staple at parties when I was a student, but at Cardiff University it actually made its way into a play written by medical students in 2016. A student actor blacked up and wore an oversized dildo to make fun of a black lecturer at the university, which unsurprisingly caused a feeling of ‘segregation’ between groups of different ethnic backgrounds.14 Eight students of African heritage complained, and this, according to the independent report commissioned by the university as a result of the incident, led to a ‘major backlash’. Some of the complainants were told by their fellow students they were being ‘very and unduly sensitive’ and that they should accept it as ‘tradition’, as the play was an annual occurrence. The students who had raised the objections felt they had been ‘ostracised’ and some decided to leave Cardiff.

Three years before, a couple of hundred miles away in York, four male students donned black face, too.15 They were depicting the Jamaican bobsled team from the film Cool Runnings. Over in Edinburgh, law students painted their faces to dress as Somali pirates for an ‘around the world’ themed party.16 Meanwhile, at the University of London, a student was actually rewarded with a bottle of wine for their racial insensitivity when they won a fancy dress competition at a union event by donning black face.17 And in Loughborough last year, students organising freshers’ events had to issue an apology after planning a ‘slave auction’ and ‘slave night’ as part of the entertainment for the university’s new intake.18 It is important to note that this kind of flippant racism is as common among those educated in the most elite of institutions as it is anywhere else. These are not isolated incidents but part of the very foundation of British society. They are being perpetrated by the bankers, lawyers and doctors of tomorrow: people who will become the managers who throw out CVs because they can’t be bothered to pronounce ‘Akua’.

A recent report19 by race-equality think-tank the Runnymede Trust highlighted the feelings of exclusion and rejection felt by many black university students as they navigate alienating curricula, come up against lower expectations from professors, and experience brazen racism on campus. The report emphasised the importance of universities becoming ‘actively anti-racist institutions’ – something that, as bastions of ‘progressive thought’ and ‘talented minds’, shouldn’t be such a big ask.

But very few universities have taken appropriate measures to prevent or punish racism, and students are often forced to take matters into their own hands. It was racist incidents such as those outlined above that led to the creation in 2013 of the Anti-Racism Society at my old university, run voluntarily by a group of undergraduates. It offers students advice or someone to talk to about race-related issues, and puts on events such as sleepovers, movie nights and panels offering often cathartic discussions about race and racism. Many students feel more comfortable reporting incidents to their peers, as opposed to their institution’s reporting systems, but those who run societies like this are under the same pressures – in terms of racial tensions and university work – as those who come to them for help. The frequency of racial abuse on campus is something that universities, not students, should handle better, but even so, these spaces, groups and organisations are important. Anti-racist societies are different to an African-Caribbean Society, where the basis of meetings isn’t always necessarily political; these societies exist specifically for tackling racism. Don’t be afraid to be the person to create that space at your university if it doesn’t already exist.

Sometimes the microaggressions can occur at the hands of the universities themselves. Femi Nylander was a recent graduate of Oxford when he found himself racially profiled. He was visiting a friend’s office in Harris Manchester College and was locked out, so he went to the office’s kitchen to do some writing, chatted briefly with staff and students he knew and then left. Later that day, a CCTV image of Nylander walking around the college was emailed to all of its staff and students, along with a message warning them to ‘be vigilant’ and to ‘alert a member of staff […] or call Oxford security services’ if they saw him. His presence, it warned them, was a reminder that the college’s ‘wonderful and safe environment’ can be taken advantage of, adding that its security officers ‘do not know [his] intentions’. No one once asked Femi who he was or why he was there.

Afua remembers her visitors also being on the receiving end of similarly racist treatment at Oxford years before:

‘I had this boyfriend in London who was black and I coped by running away a lot on the weekends and hanging out with him, and then he’d come and visit me and that was a big issue because he was a dark-skinned black man. One time when he came to my college, they wouldn’t let him in and the porter rang me and said: “You should’ve warned us if you were expecting someone who looked like a criminal,” and I’ll never forget that. Even then, I was like, I cannot believe I’m having to put up with this. It was like there was no sense that … It was really bad and I was very conscious of being with him at Oxford because it kind of drew further attention to me as a black woman.’

These types of everyday microaggressions have sparked several conversations and motivated various campaigns, one of the most high-profile being the ‘I, too, am Oxford’ series, inspired by the ‘I, too, am Harvard’ initiative in America. In 2014, Oxford students organised a photoshoot consisting of 65 portraits of BAME attendees of the university, with the hopes of highlighting the ignorance they came across at Oxford – and confronting it. ‘How did you get into Oxford? Jamaicans don’t study’, ‘But wait, where are you really from?’ and ‘I was pleasantly surprised … you actually speak well!’ were just some of the choice quotes written on the placards they held in front of them, forcing their peers to encounter the ugly face of university racism. It is hugely important that black students continue to have these conversations and to hold their universities to account, especially when white students so often centre racial discourse around themselves. During Afua’s time at university, even the ACS wasn’t a black safe space:

‘I joined the African-Caribbean Society only to discover that it was run by a white boy from one of the elite private schools in the country because he loved going to Jamaica to his dad’s villa in the summer holidays and he had fancied being a “DJ reggae man”. At the time, I was just like, this is completely off, but I couldn’t articulate it. It was classic white privilege, exoticisation.’

Perhaps as a result of the slowly increasing black student population, the voice of black students is beginning to be heard in universities in a way it hasn’t been before, as Afua explains:

‘For my book, I interviewed some black female students and it was interesting listening to them, because on one level they were describing the same microaggressions that we experienced, i.e. getting IDd when you were going to different colleges whereas white people weren’t, or porters confusing you with the one other black person in the college even though you looked nothing alike, that kind of thing. But their attitudes were so different: they had names for it. We didn’t have a word for microaggression and they had a confidence and ability to articulate their sense of oppression that I really admired. Even though on one level it was an acknowledgement that a lot of things hadn’t changed, I found it really positive and uplifting speaking to these students because they were much more organised and assertive and they called things out when they saw them, whereas we just didn’t feel able to. We would talk about it amongst ourselves but we just kind of had a defeatism about it.’

It may be that we now feel less apologetic about taking up space in a country that is rigged against us but which many of us still consider ours. But even with our newfound ability to speak up, some students still remain negatively affected by racism at university. In fact, the government was called on to take ‘urgent’ action after it emerged that black students are more than 50 per cent more likely to drop out of university than their white and Asian counterparts. More than one in ten black students drop out of university in England, compared with 6.9 per cent of the whole student population, according to a report by the UPP and Social Market Foundations.20 The government have made a whole heap of noise about increasing the numbers of black students enrolled at certain British universities, but the problem of how to keep them has been largely neglected. London universities are more likely to have a higher proportion of black students in attendance – and it’s no coincidence that London has the highest drop-out rate of all the English regions, with nearly one in ten students dropping out during their first year of study.

‘My best friend at Oxford, she dropped out in the third year,’ Afua says. ‘She was doing a four-year degree and she dropped out because she felt like she wasn’t good enough. She just didn’t believe in herself enough, she couldn’t cope. It was literally just Imposter Syndrome, like, “Everyone else is better than me, cleverer than me and they deserve to be here.” She went to a state school, she had a multiple sense of illegitimacy there and she took a year out, she came back and she got a first. I found that interesting because there was no question about her intelligence or her deserving to be there; it was just that sense of acceptance. I think it’s really common – I was reading a report about how drop-out rates are higher for black students, and I’ve been mentoring a student, who, ironically, is from a very similar background to my friend and doing the same degree, and who just dropped out last year. It’s so frustrating that you can’t tell someone to stay somewhere that makes them feel unhappy but you do wonder, if this person had been supported, would this have happened?

‘I think universities just assume that their jobs are to just get a few black people through the door. They have no sense of the extra emotional burden that we carry by being there, so they don’t do anything proactive to support us. I nearly dropped out in my first year and it was basically like: if you’re not up for it, then good riddance. There was no “How can we support you?”, “What’s going on here?”, you know? There was just no intellectual curiosity as to what this phenomenon was, which ironically just confirmed why I wasn’t supposed to be there anyway, because the possibility of me not being here doesn’t remotely bother anyone.’

The reasons why black students’ drop-out rate is higher than other groups are complicated and multifaceted. According to one report,21 many universities struggle to respond to the ‘complex’ issues related to ethnicity, which tend to be ‘structural, organisational, attitudinal, cultural and financial’. Other factors mentioned were a lack of cultural connection to the curriculum, difficulties making friends with students from other ethnic groups and difficulties forming relationships with academic staff, due to the differences in background and customs. The report also cited research showing that students from ethnic backgrounds are much more likely to live at home during their studies, perhaps making it less easy to immerse themselves in campus life. But Dr Nicola Rollock believes that not enough is being done to investigate the underlying causes of this:

‘My concern is that these issues aren’t looked at in any fundamental way: when they are, all black ethnic groups are amalgamated into one mass, and they shouldn’t be. The data doesn’t speak to distinct differences. And there’s also a fear of talking about race. If they’re talking about black and minority ethnic students, race needs to be a fundamental part of that conversation, but I would argue that as a society, and certainly within the academy and within education policy, race is a taboo subject. People are scared of talking about race and when they do, they do so in very limited terms. They believe that treating everybody exactly the same is the answer. Or particular tropes will come out for example: “These groups need mentoring,” or “These groups lack confidence,” or that “There are not enough groups coming through the education pipeline,” and while I’m certainly not rejecting any of these points, I argue that to only focus on such issues is to miss the wider picture. Some people do have confidence but yet they are not progressing. How do you explain that? So I think there is a real limited and poor engagement with race both within the academy and education more broadly.’

.....................................................

‘Sound so smart, like you graduated college.’

.....................................................

Going on to higher education, wherever it may be, and for whatever period of time, is an achievement. To choose to extend your full-time education, to opt in to taking more exams and willingly take on ever-increasing student debt, is deserving of a pat on the back. But it’s notable that while black British youths are more likely to go to university than their white British peers,22 they are also much less likely to attend the UK’s most selective universities. This is not an indictment of the universities that aren’t ranked at the top of the league tables, nor is it an endorsement of the frankly elitist system that sees some universities undervalued. Further education is just that: the furthering of education, and wherever that happens it should be valued. But it’s important to interrogate why the under-representation of black people in these institutions occurs, especially when statistics show that there are more young men from black backgrounds in prison in the UK than there are undergraduate black male students attending Russell Group universities.23 Black Britons of Caribbean heritage make up 1.1 per cent of all 15- to 29-year-olds in England and Wales and made up 1.5 per cent of all British students attending UK universities in 2012–13.24 Yet just 0.5 per cent of UK students at Russell Group universities are from Black Caribbean backgrounds,25 and there is little understanding of why this is the case.

One given reason is grades: black students are less likely to achieve the required results for entry to highly selective universities, which could help account for their lower rates of application.26 The stumbling blocks that affect black students in school are outlined in the previous chapter, and help contextualise why this often happens. But the more pressing issue that many gloss over is that even when they do achieve the same results,27 black applicants are less likely to be offered places than their white peers. In 2016, despite record numbers of applications and better predicted A-level grades (and the fact that UCAS predicted 73 per cent of black applications should have been successful),28 only 70 per cent of black applicants received offers of places, compared to 78 per cent of white applicants.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.