Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Ship of Dreams», sayfa 3

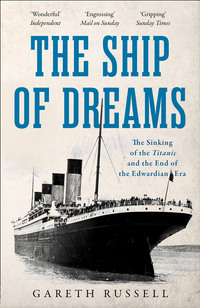

‘Down to the river with a grace and dignity’: the launch of the Titanic.

Launch of the RMS Titanic at Belfast, 31 May 1911 (By kind permission of Daniel Klistorner from his personal collection)

Cheers erupted from the onlookers, hats and handkerchiefs were waved in the air; small river craft sounded their sirens, as chains created enough drag to stop the Titanic slamming into the other side of the river.[45] With no funnels or masts and empty interiors, she came to a gentle stop in the water and attention turned to the completed Olympic, which the Titanic would one day so closely resemble. A journalist from the Shipbuilder, the industry’s most respected trade journal, waxed lyrical about White Star’s new flagship, half as heavy again as the previous record holder, the Cunard Line’s Mauretania:

The Olympic is the most beautiful boat ever built on Queen’s Island. The grace and harmony of her lines were admired by the thousands of enthusiasts who saw her on the day of her launch, but since then the work on her has been advanced, and her four massive funnels seem to add immeasurably to her splendour and dignity. Her majestic proportions and her unparalleled dimensions tend to enhance her picturesqueness and power, and one can well understand the interest with which the builders and owners are anticipating her maiden voyage … In her equipment she possesses features that are not to be found on any other boat.[46]

Among the new features celebrated in the press, the Olympic offered the first lift for second-class passengers and the first swimming pool at sea, in First Class.[47] Three weeks later, she arrived to a rapturous welcome in New York, returning eastward on 28 June with a record-breaking number of first-class passengers.[48] Both the Olympic and the Titanic had nearly as many berths for first-class travellers as for Third, a reflection of the growing number of wealthy people travelling across the North Atlantic on a regular basis, apparently justifying the White Star Line’s investment in the future earning potential of the privileged. For all the talk of an assault on the established order, the world spun onwards, simultaneously contented in the accumulated treasures of a century of economic progress and tense at the uncertainty of what lay ahead. When the grouse-shooting season was over, the King and Queen sailed to India for a theatrical and manufactured ceremony at which they were crowned Emperor and Empress of India. One peer’s daughter in attendance marvelled at the maharajahs’ jewels as ‘a thing to dream of – great ropes of pearls and emeralds as large as pigeon eggs such as I have never seen before’, though she thought it ‘so strange to see them adorning men’.[49] The old boys’ network flourished in the King’s absence when, to the surprise of many, including himself, the recently elected MP Sir Robert Sanders was invited to become one of the Conservative and Unionist whips. In his diary, he stated with crushing self-honesty, ‘I believe I owe it mainly to the fact that I was a successful Master of the Devon and Somerset [Staghounds].’[50]

In Russia, the Tsar’s eldest daughter, the Grand Duchess Olga, made her debut into Society with a 140-guest candlelight supper at her family’s Crimean summer palace. At the ball that followed, wearing her first floor-length evening gown, its sash pinned by roses, the Grand Duchess was partnered in her first waltz by her father. The sixteen-year-old had her first sip of champagne and one of her mother’s ladies-in-waiting rhapsodised over ‘the music of the unseen orchestra floating in from the rose garden like a breath of its own wondrous fragrance. It was a perfect night, clear and warm, and the gowns and jewels of the women and the brilliant uniforms of the men made a striking spectacle under the blaze of the electric lights.’[51]

In Austria, hat-wear changed as usual with the Vienna Derby marking the point at which it became de rigueur for gentlemen to switch from derbies to summer boaters, while later in the Season the country’s octogenarian Emperor, Franz Josef, was seen in a rare public good mood when he visited the village of Schwarzau for the wedding of his great-nephew, the twenty-four-year-old Archduke Karl, to Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma.[52] That evening, cheering villagers processed in torchlight celebration past the imperial couple as a prelude to a fireworks display over the castle.[53] Born in Italy to a French family, educated at a Catholic boarding school in Britain, fluent in six languages, walked down the aisle by the Duke of Madrid, married by the Pope’s personal representative, granddaughter of a king of Portugal, great-great-granddaughter of the last Bourbon king of France, first cousin of the Queen consort of the Belgians and sister-in-law of the Bulgarian Tsar, the new Archduchess Zita was a reassuring return to marital form for a Habsburg heir, after the first in line had caused collective palpitations a decade earlier by proposing to a commoner.[54] She had been a countess, but to the Habsburgs he might as well have walked up the aisle with Rosa Luxemburg.

As summer bled into autumn and winter, the great migrations began. After ‘two terrible years’ watching her marriage disintegrate under the strain of her husband’s mental ill-health, the American novelist Edith Wharton went skiing in St Moritz, where she was joined by her friend, the Italian nobleman Prince Alfonso Doria-Pamphilj.[55] The new American Ambassador to Germany, a former vice-president of Carnegie Steel, invited the Second Vice-President of the Pennsylvania Railroad and his wife to visit him and the Consul General in Berlin. Crossing the Atlantic not long after them was the co-owner of Macy’s department store and his wife, fleeing the Manhattan blizzards for the restorative warmth of Cannes. They arrived in France as another of their compatriots was leaving it: the London dinner-party circuit had it that the American socialite Gladys Deacon had quit Paris to rent an apartment at 11 Savile Row in London, above Huntsman the Tailor, fuelling rumours of a reconciliation with her unhappily married lover, the Duke of Marlborough.[56]

Noëlle and Lord Rothes spent a week as guests at a hunting party given by their friend the Marquess of Bute and they hosted their own autumnal shooting weekends at Leslie House as usual.[57] It was a splendid home for entertaining and despite the recent financial and political pressures on the aristocracy, to outward appearances it remained as majestic and tranquil as it had been for centuries. Leslie House had, within a generation of its construction in the seventeenth century, been referred to as a palace by visitors, who favourably compared it to William III’s residence at Kensington Palace and his controversial imitation of Versailles, for which he had ordered the demolition of half of the original Tudor wings at Hampton Court Palace.[58] Leslie House had boasted two courtyards, an entrance hall ‘pav’d with black and white Marble’, and one of the finest private libraries in Great Britain. Then, early in the reign of George III, much of that splendour went up in flames.[59] Snow was falling as three-quarters of Leslie House burned in the night air, immolating one of the courtyards and the entirety of the library. Some sources give the date of the fire as Christmas Day 1763; others say it was three days later, on the Feast of the Holy Innocents. Either way, there is a general agreement of a Yuletide conflagration.

One feature that survived the 1763 Leslie House fire was a magnificent gallery, three feet longer than its counterpart at Edinburgh’s Palace of Holyroodhouse, the Royal Family’s official residence in Scotland. There, in paint and tapestry and silver, unfurled the genealogical and political history of the Leslies. Like most ancient aristocratic families, the Leslies have their own contested origin myth in the mist-shrouded centuries of document-deficient antiquity. In their case, that a Flemish or Hungarian baron called Bartholomew arrived in Scotland in the entourage of Margaret of Wessex, an eleventh-century English princess and subsequent saint, who had been raised in exile in Hungary before her marriage to King Malcolm III, and a series of legends arose about his subsequent career in Scotland.[fn3] Much of the more lovely nonsense associated with Bartholomew’s life was politely disbelieved by many of the later Leslies themselves who, in 1910, submitted evidence to The Scots Peerage that their first recorded grant of land had arrived at some respectably distant juncture in the 1170s, when a Malcolm Leslie, traditionally described as Bartholomew’s son, had been a recipient of royal largesse from William the Lion, King of Scots.[60]

From there, a fusion of family legend and historical evidence placed a Leslie on the Crusades, another pledging allegiance to Robert the Bruce in his quarrel with England’s Edward Longshanks, and others representing Scotland on diplomatic missions to the courts of Pope John XXII and King Edward III of England. A spirit of ferocious devotion to the Crown, seemingly equally nurtured by loyalty and ambition, had pushed the Leslies upwards as the centuries wore on. The first recorded mention of them in possession of the earldom of Rothes dates from March 1458, after they supported King James II in his torturous dispute over the earldom of Mar. In the next generation, they continued to aid the consolidation of royal authority under the Stewart monarchs, who ruled Scotland from 1371 to 1714. The 3rd Earl of Rothes fell in combat at the Battle of Flodden, while supporting James IV’s failed invasion of England; his son, the 4th Earl, himself tussled unsuccessfully with Henry VIII’s armies, this time at the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542, but survived to attend James V at his deathbed, and later represented his kingdom at the Parisian wedding of Mary, Queen of Scots, to the future King François II of France. That Earl’s death, on his way home, from food poisoning was, probably erroneously, attributed to the French family of Scotland’s Queen Mother, Marie de Guise, in retribution for the Leslies’ vigorous involvement in the assassination of her adviser, Cardinal Beaton. The dagger used to stab His Eminence was still, in 1911, mounted in the Leslie House gallery, next to a portrait of the accidentally poisoned Earl’s son, the 5th Earl of Rothes, who had ended the family’s brief flirtation with disloyalty by holding his allegiance to Mary, Queen of Scots, long after her deposition and despite finding themselves on different sides of the confessional aisle created by the Protestant Reformation.

A generation later, when Mary’s son, James VI, inherited the English and Irish thrones as their King James I, the Leslies’ fidelity to the reigning house eventually catapulted them into the national trauma that English histories refer to as ‘the English Civil War’, but which might more properly be remembered by its British name of ‘the War of the Three Kingdoms’, given its appalling impacts on all the constituent parts of what later became the United Kingdom. The Leslies supported King Charles I even as the monarchy entered freefall. Also mounted on their gallery walls was the Sword of State carried by the 7th Earl at the first coronation of King Charles II at Scone in 1651, after Scotland had refused to accept the legality of Charles I’s execution or the English republican regime that had arisen in its wake. Ruinously fined for their loyalty to the deposed royals, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 brought the Leslies back into the sunlight of governmental favour. Next to the portrait of the 7th Earl and his monarchy-affirming sword, the gallery boasted, near one of Rembrandt’s self-portraits, a likeness of Mary of Modena, the last Catholic queen consort in Britain.[61] In recognition of their steadfastness to the royalist cause, Charles II had granted the ‘able and magnificent’ 7th Earl of Rothes the unusual honour of allowing his title to descend through or to the female line. This royal gratitude had prevented the Leslies from stuttering into oblivion thanks to the lack of a Y-chromosome, on which rock so many other noble families had perished. Through the 7th Earl’s overzealous defence of royal-led Anglicanism in Scotland in the seventeenth century, his immediate descendants’ refusal to support either of the Jacobite rebellions in the eighteenth, or the service of the 10th Earl – rendered for the gallery’s posterity by the brush of Joshua Reynolds – who had accompanied George II as one of his generals to the Battle of Dettingen, the Leslies had remained conspicuously loyal to the British monarchy, regardless of the head of the family’s gender. Also in their gallery was a beautiful old tapestry that depicted the mythical, fatal voyage of Leander, crossing a darkened, storm-struck stretch of sea in pursuit of Hero.[62]

Clan Leslie and the Rothes earldom had a history that tied them to the developments of the Scottish kingdom, then Great Britain, the United Kingdom and its empire. They had faced many obstacles over the centuries and it was clear that after 1911 they would face more. To maintain Leslie House, not only had Noëlle invested a substantial amount of her own inheritance but Norman had sold various parcels of land and considered other income-generating projects. After the frantic social whirl surrounding the coronation, Norman planned to skip the next London Season with a prolonged trip to America where he would undertake a fact-finding mission for the British government and also explore the possibility of investing in the New World.

2

The Sash My Father Wore

Cursèd be he that curses his mother. I cannot be

Anyone else than what this land engendered me:

… I can say Ireland is hooey, Ireland is

A gallery of fake tapestries,

But I cannot deny my past to which my self is wed,

The woven figure cannot undo its thread.

Louis MacNeice, ‘Valediction’ (1934)

IN THE SMALL HOURS OF THE MORNING OF TUESDAY 2 April 1912, before the electric trams with their recently added roofs commenced their shuttle into the city centre, a Renault motor car waited on tree-lined Windsor Avenue in south Belfast.[1] The residential street, full of alternating white and redbrick mansions, ran between the Lisburn and Malone roads, the axis of upwardly mobile prosperity that was both child and parent of the city’s most affluent suburb. Like Windsor Avenue’s homage to Britain’s most famous castle, many of Malone’s public spaces had adopted royally inspired names which proclaimed the area’s loyalty to the throne along with, perhaps, a faint sense of self-identified social kinship with its incumbent. Twenty years earlier, the residents had ditched the workaday address of Stockman’s Lane, at the bottom of the Malone Road, to rechristen it Balmoral Avenue, in a nod to Queen Victoria’s favourite home.[2] Near by, various streets and stations were named in honour of Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, William IV’s queen; Belvoir and Deramore honoured a late Tory baron; the Annadale embankment, which lines the slow-flowing waters of the Lagan river where young medical students practised their rowing on weekend mornings, was named for another deceased local aristocrat, Anne Wellesley, Countess of Mornington.[3] Later, when a school was founded near the Annadale embankment, it was called Wellington after Anne Wellesley’s son, the 1st Duke of Wellington.[4] Shaftesbury Square, the urban gateway to south Belfast, bore the name of an earldom with historic influence in the north of Ireland, while multiple streets and buildings paid tribute to the Chichester family and their marquessate of Donegall.[fn1] There were various parks, roads and avenues with the prefix of Osborne in honour of Queen Victoria’s former summer house on the Isle of Wight, while Sans Souci Park, near the top of the Malone Road, widened the geography of homage, if not the class, by choosing as its inspiration the baroque palace built for King Friedrich the Great of Prussia.

In neighbouring Stranmillis, the suburb that intersects Malone, newly completed streets were given the name Pretoria to commemorate imperial victories in southern Africa. On the other side of the river, the Ormeau neighbourhood created roads called Agra, Baroda and Delhi, after areas of the British Empire in India. Botanic, the final stretch of land before south Belfast gave way to the city centre, contained new avenues after seventeenth-century British generals or, like Candahar Street, to celebrate successful colonial expeditions into Afghanistan.[5]

From his home on Windsor Avenue, Thomas Andrews, the thirty-nine-year-old Managing Director of the Harland and Wolff shipyards, stepped into his waiting car before it turned towards the Malone Road.[6] He left behind his wife of four years, Helen, and their two-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. Andrews, who would be gone for several weeks supervising the maiden voyage of the Titanic, was ambitious and almost fanatically dedicated to his career, but when he travelled he suffered dreadfully from homesickness, particularly after the arrival of little Elizabeth.[7] One of the five servants they employed was a nurse for the toddler.[8] His car turned left on to Malone to continue its journey towards east Belfast, where the Titanic was docked in preparation for her sea trials.

Thomas Andrews, c.1912.

Thomas Andrews Jr (Historic Images/Alamy Stock Photos)

Tall and softly handsome, with a trim build, dark hair and brown eyes, Andrews – known as Tommy to his family and closest friends – had the elegant manners and unfailing kindness with which even the most exacting of aristocratic etiquette experts would have struggled to find fault. His work in the shipyards brought him into regular contact with men from all walks of life – be they industrialists, like his uncle Lord Pirrie, or semi-literate labourers from east Belfast, some of whom brought their seven- or eight-year-old sons to work in the shipyard because they could not afford to send them to school. Andrews’ total lack of snobbery, his sense of fairness and his gentle tone in conversation endeared him to most of his colleagues and helped spare him from accusations of nepotism.[9]

As Andrews’ automobile moved down the gentle slope that marked the end of the Malone Road, he passed the still-slumbering accommodation of the 400 or so students of Methodist College.[10] A boarding school with a white Maltese cross for its crest, ‘Methody’, as it was known by locals and alumni, had a stellar reputation for academics and sports. Two weeks earlier, its rugby team had competed in the Ulster Schools’ Cup Final, a match held annually in Belfast on St Patrick’s Day, in which the two best squads in the north of Ireland played against one another. That March, rather gratifyingly for Tommy Andrews, Methody had played and lost 11–3 against his own alma mater, the Royal Belfast Academical Institute.[11]

‘Inst’, as it was and is referred to for reasons of ease, laziness and affection, lay less than a mile from Methody. Tommy Andrews, like his brothers John, James and William, was proud of their status as ‘Old Instonians’, regularly contributing to fund-raising for the school sports and prizes. Cricket had been one of Andrews’ favourite clubs as a pupil and he retained a keen interest in the sport.[12] Between them, Methody, Inst and Victoria, the all-girls school which then had its campus halfway between them, were consciously turning out sons and daughters of the British Empire.[13] It was one generation’s duty to prepare the next. In east Belfast, the late textile magnate Henry Campbell had left a bequest to found an all-boys college that bore his name. Every year, Campbell College, which operated an Officer Training Corps as part of its extracurricular activities, celebrated Empire Day, during which the head prefect would plant a tree in the school grounds, symbolising with each passing year and each new tree the empire’s continued growth and the shelter it would provide to its obedient subjects. Its founder’s will stated that Campbell was ‘to be used as a College for the purpose of giving there a superior liberal Protestant education’ and, flowing from all the schools that dotted the emerging or established suburbs of middle- and upper-class Belfast, there was a steady stream of young men and women who would ‘Fear God and serve the King’.[14]

Tommy Andrews had benefited from this kind of education that inculcated Protestantism, patriotism and propriety in almost equal measure. Like many residents of Malone in 1912, Andrews displayed the easy-going grace popularly associated with the patrician classes but, again like Malone itself, he was in reality a product rendered in its final form by the plutocracy, the expansion of the British Empire and its Industrial Revolution. The other prominent families in Malone were, like Andrews, tied to trade. His wife, Helen, came from the Barbour family of linen merchants. The Johnstons and MacNeices had been made rich by tea; the Andrewses’ immediate neighbours, the Corrys, were in timber. The Stevensons ran Ireland’s largest printing press and its second-largest glue factory. The McDonnells, father, son and grandson, were lawyers. Most of Maryville Park’s grand homes were occupied by Andrews’ similarly well-paid colleagues from Harland and Wolff. The former south Belfast home of Lord Deramore was now rented by the Wilsons, who had made their fortune in the property boom of the 1890s. By 1912, the aristocracy’s influence in the day-to-day life of Belfast looked set to contract to matters of taste and prestige by proxy.

It was a trend in time that had worked in the Andrewses’ favour. Tommy had learned to ride to hounds, becoming a skilled horseman and hunter, and he had played cricket at his local club – where his love of the sea earned him the nickname ‘the Admiral’ – but despite these activities neither he nor his ancestors had ever been part of the Ascendancy.[15] The family had been based in the village of Comber, 11 miles outside Belfast, since the seventeenth century, when another Thomas Andrews had established the local corn mill, which turned near their pretty house, Ardara, product of its profits. By the time Tommy Andrews was born at Ardara in 1873, the house and its lawns had acquired a mature grace, reached by an avenue lined with rhododendrons leading down to the gleaming waters of Strangford Lough.[16] The Andrewses’ sustained upward trajectory over the course of the nineteenth century had been part of Britain’s quiet revolution in local government, as the increasing complexity and size of modern bureaucracy saw power shift permanently from the hands of the landed classes to those of useful local businessmen, who became loyal politicians. Along with ownership of the mill and serving as Chairman of the Belfast and County Down Railway Company, Tommy’s father was High Sheriff of the county, Chairman of the Down County Council and President of the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association.[17] His uncle, William Andrews, was a judge in the Irish High Court; both had been made Privy Councillors during the celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897.[18] Tommy’s maternal uncle, Lord Pirrie, remained Chairman of Harland and Wolff while being twice elected Lord Mayor of Belfast and elevated to the peerage for his philanthropy, and Edward VII had approved his induction into the Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick, a chivalric order of knighthood once reserved for sons of the Hibernian nobility.[19]

Tommy’s car progressed from the quiet avenues of Malone to a city centre dominated by sprawling temples to commerce. During working hours, this part of Belfast was a hive of activity, described by The Industries of Ireland as a place of ‘crowded rushing thoroughfares [where] we find the pulsing heart of a mighty commercial organisation, whose vitality is ever augmenting, and whose influence is already world-wide’.[20] No other town in Ireland had benefited so significantly and unambiguously from the successes of the British Empire. As Britannia’s boundaries were set ‘wider still and wider’, Belfast had boomed and its growth seemed only to accelerate. Its population had risen seventeen-fold over the nineteenth century, with the biggest spurt occurring in the final twenty-five years, when it had doubled.[21] From a town that still, in 1800, had operated as a fiefdom of the marquesses of Donegall, Belfast had, by 1900, become one of the largest urban centres in the United Kingdom, dominated and defined by its industries.[22] Granted city status in 1888, a mere three years later Belfast had outstripped Dublin in terms of population and living standards.[23] To celebrate, Belfast’s City Council, with the hungry and gaudy vitality of a newly enfranchised adolescent, approved the construction of a Grand Opera House, where audiences sat beneath a dome decorated with paintings of cheerfully obedient life throughout Queen Victoria’s Indian dominions as goldleafed elephants gazed down from the front-facing corners of the proscenium arch.[24]

The Opera House had been part of a building mania that swept Belfast in the twenty years preceding the Titanic’s construction. The spires of the seven-year-old Protestant St Anne’s Cathedral were visible as Tommy Andrews’ car turned right from his former school to motor down Wellington Place and pass the new City Hall, a looming quadrangle in Portland stone, with ornamental gardens, stained-glass windows, turrets and a soaring copper dome. Completed two years after St Anne’s, the City Hall had cost more than £350,000, a sum that had not been without controversy, especially for some of the city’s more parsimonious Presbyterians. But there were many more, including Belfast’s Chamber of Commerce, who had applauded the council’s extravagance on the grounds that a powerhouse like Belfast, ‘a great, wide, vigorous, prosperous, growing city’, needed to be represented with appropriate splendour.[25]

As a younger man, Andrews had been there to witness the surge of capitalist confidence in Belfast’s heartlands. The journey from Comber to the city was too long for the early-morning starts required by the shipyards, so after he had secured his apprenticeship aged sixteen Andrews became a boarder in the home of a middle-aged dressmaker and her sister on Wellington Place.[26] From there, he had witnessed the construction of the City Hall in the same years as Belfast inaugurated its new Customs House, a Water Office built to imitate an Italian Renaissance palazzo, and four banking headquarters.

Belfast’s Donegall Square North. Robinson and Cleaver is on the left.

Panoramic view from the corner of Donegall Square West, by Robert John Welch (© National Museums NI)

Directly in front of City Hall, between its imposing entrance and its wrought-iron gates, a statue of Queen Victoria stared unseeing towards the sandstone turrets of Robinson and Cleaver, one of the most expensive and prestigious department stores in the United Kingdom. Inside the ‘Harrods of Ireland’, 3,000 square feet of polished mirrors lined the shop’s interiors, spread over four working floors, all connected by white marble staircases, at the top of which stood statues of Britannia.[27] Belfast’s well-heeled customers flocked to Robinson and Cleaver, as did prosperous members of county Society, who were prepared to pay for goods shipped ‘from every corner of His Majesty’s Empire’. Reflected in Robinson and Cleaver’s mirrors were busts of the store’s most august clients, including the late Lady Lily Beresford and Hariot Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, one of the bluest of the Ascendancy’s blue bloods as Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, who had used her time in India as wife of the British Viceroy to campaign for better medical care for Indian women and introduce Robinson and Cleaver’s produce to the Maharajah of Cooch-Behar, who now also stood beside her in bust form, along with Queen Victoria’s German grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his consort, Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, who had temporarily overcome her pathological hatred of Britain to place repeated orders with the firm.[28]

Many of the craftsmen who worked on the construction and decoration of Robinson and Cleaver, and then on the interiors of City Hall, had also laboured on the ships designed by Tommy Andrews for Harland and Wolff.[29] His car passed the earliest rising of these workers as they travelled on foot, by bicycle or by tram over the bridges linking the city centre to the east, Queen’s Island, and the shipyards. The majority of these dawn risers were on their way to work on Andrews’ latest and grandest creation, the Britannic, whose hull had been laid amid the driving Belfast winter rains six months earlier.[30] As the journey of a million miles begins with a single step, the foundation of the largest ship built on British soil for the next two decades was already taking shape in her embryonic form. Britannic was not scheduled to grace the waters of Belfast Lough for another two years and her maiden voyage to New York was timetabled for the spring of 1915, at which point she would become the flagship of the White Star Line, completing the Olympic-class.[31]

End of the day: workers from Harland and Wolff with an under-construction Titanic in the background.

Queen’s Island workmen homeward bound, by Robert John Welch (© National Museums NI)

The relationship with White Star Line was a source of pride to many in Belfast, which was hardly surprising considering the employment and revenue it generated, both of which were regularly cited in speeches by city officials and businessmen as among the many reasons for Belfast’s superiority over other Irish cities, a conclusion with which Andrews wholeheartedly concurred.[32] Even in the very poorest parts of Belfast, all houses were single-occupancy units for families. Unlike Dublin or Cork, Belfast’s leaders had worked hard to avoid the horrors associated with the special strain of poverty bred in tenements. Alongside the thick brogue of natives, Scottish and English accents could be heard in the jostling crowds that poured from the Protestant working-class neighbourhoods, their owners lured to Ulster by promises of affordable, good-quality housing through jobs at Harland and Wolff, in one of Belfast’s 192 linen manufacturers or in its behemoth-like rope or tobacco factories.[33] Belfast had one of the lowest urban rates of infant mortality in the British Empire; with eighty-two state-funded schools, it also had the highest rate of literacy for any area in Ireland, and it implemented provisions for the care of the deaf and dumb long before most other towns.[34] As its two synagogues, built by the migrant-turned-merchant-turned-city mayor Sir Otto Jaffe, attested, Belfast was also so far the only section of Ireland to welcome and nurture a Jewish community.[35] In the eyes of the loyal, all this was abundant proof that Belfast had benefited from the spirit of dynamic, self-fulfilling conservatism that guided its civic authorities and indelibly separated it – in spirit and soon, God willing, in law – from the south.[36]

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.