Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

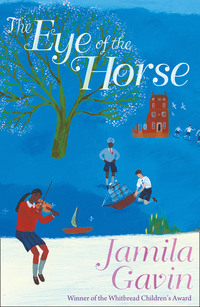

Kitabı oku: «The Eye of the Horse», sayfa 2

‘Hiya Ram, Ram, Ram!’ were the last words on the Mahatma’s dying breath.

‘The light has gone out of our world,’ wept the Prime Minister.

Later that day the horse was seen again, galloping in a frenzy down the long white road. Some said a strange rider crouched on its back; some demented creature with wild hair flying – small as a child or a hunchback.

But that night, the horse came again to the palace. Bublu heard its footfall on the terrace. Bublu moved with the silence of a hunter. This time, he would catch it. He heard its breath and saw its white shape gleaming in the darkness. It looked up. The horse saw him with glittering eye. It didn’t run away. Bublu held out a hand of friendship. ‘Come to me, my beauty! Don’t run away. Come to me, O wondrous one!’

As he spoke, he moved closer and closer. Now he could feel its warm breath as he held his hand up to its nostrils. He stroked its nose and murmured lovingly to it. ‘Let’s be friends. Stay with me. I’ll feed you and groom you and ride you well. Stay, my beauty.’

The horse stood stock-still. Then Bublu realised that, sheltering beneath the horse’s belly, protected between its four legs, crouched a creature with long wild hair. In the darkness, he couldn’t make out the face, but its eyes, like the eyes of a snake, stared at him, glittering and hypnotic.

Bublu cried out loud with shock, but still the horse didn’t move.

What had come to them? What was this creature? Was it a demon? Was the horse a bringer of bad luck? Bublu remembered the words of the old sadhu.

He dared not move either towards the horse or back to his place by the fire. Instead, wrapping his sheet around him, Bublu sank down on his haunches, and stayed like that for the rest of the night, with his head sunk on to his arms.

FOUR

Train Tracks

Jaspal leaned over the old metal bridge and looked down onto the railway tracks below. The shining metal slithered away like parallel serpents, till they reached a point in the distance where they merged as if one – but he knew that this was only an optical illusion.

The sight of the tracks always gave him an intense feeling of excitement. Sometimes, when the sun was shining in a particular way, he could block from his view the grubby backs of those London houses and flats, with their grimy windows and straggles of grey washing hung out to dry. He could fix his eye on the patch of blue sky between the tenements, and imagine he was back in India. For a while, he could try and forget the pain which sat in his stomach like a hard lump.

Trains reminded him of his village back home in Deri. Beyond the mango and guava groves and between the fields of wheat, mustard seed and sugar cane, the railway track ran the length of the Punjab skyline.

He and his best friend, Nazakhat, had loved trains. On many an afternoon after school, they would take the long way home so that they might get over to the track and walk on the rails. There was no chance of being run down by a train, as you could see as far as the horizon in each direction. Anyway, long before the train was in sight, you could feel the hum of its power beneath your feet. It was often the smoke they saw first, streaming a long trail in the sky, and then they would hear the piercing shriek of its whistle, which carried all the way to the village.

Although there was no need for danger, they often created it.

‘Let’s see who’ll jump off first,’ Jaspal had shrieked to his friend, as the train came nearer. They had waited and waited, giggling and wobbling about with arms outstretched for balance, each on his rail. Jaspal was to leap off on one side, Nazakhat to the other. As the train bore down on them, the engine driver would often be leaning out of his cab swearing and cursing at them, shaking his fist and telling them to get out of the way. But they would just shake their fists back, mouthing unmentionable insults and then, at the last minute, fling themselves aside.

Jaspal smiled at the memory. If only it was only the good times he remembered. But trains pounded through his dreams at night. Indian trains, filled with refugees, escaping from the mayhem which was caused when India was split into two to create Pakistan; when Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs set upon each other with vicious fury, and people were driven hither and thither. The shriek of the train whistle had been a scream of death; a scream of hatred and murder and massacre. He had seen it. The images would never go away, though he tried to forget. He tried to forget the day they fled from their village. He, his sister, his grandmother and mother set off for Bombay. His mother, Jhoti, had been saving small amounts of money each time Govind sent anything from England. She had this dream, this conviction, that they would be able to buy themselves tickets on a ship bound for England. ‘If your father won’t come to us, then we will go to him,’ Jhoti had declared. Such were the desperate times, everyone was rushing around trying to work out strategies for survival. There was no one to tell her whether or not she had enough money, what papers she would need or how she would get there. With thousands of others, she had simply set off for the nearest railway station.

In the pandemonium of overcrowded platforms and trains packed with refugees, Jhoti and her children were separated from each other. The force of the crush swept Jaspal and Marvinder onto a train, which then moved off, carrying them helplessly away. Now he and his sister Marvinder were here in England while their mother and grandmother had been left behind to an unknown fate. The pain of those memories was too much to bear. Mostly, he kept them locked away in the dark recesses of his mind. Better, instead, to remember his games and his friends – especially, Nazakhat.

There was a clicking sound of a signal being raised. A train must be coming. It would be the express bound for Bournemouth and the south coast. Jaspal felt the same old excitement. If only Nazakhat could see this. He pulled a notebook and pencil out of his pocket and heaved himself up onto the parapet, so that he could get a good view of the name and number of the engine. He could hear it now as it pounded nearer. A thrill of anticipation ran through him.

Suddenly a voice yelled over the increasing roar. ‘Oi!’ Jaspal dropped down and turned. ‘Hey! Blackface! Bandage-head!’ Johnnie Cudlip stood on the other side of the road, leering at him. Although he was only a little older than Jaspal, he was a big boy for his age. Taller by a head and shoulders than any of his peers, his body was clumsy and unwieldy, as if he wasn’t sure what to do with it. His hands looked extra large, sticking out from the sleeves of the blazer he had outgrown six months ago.

Johnnie hated school because it made him feel stupid. Because teachers, who were hardly taller than he, crushed him with sarcasm and seemed to forget that, though he was as tall as a man, he was only a child. Out in the playground and the streets, it was a different story. There, he was king. There, he ruled. He was the leader of a terror gang. All the children feared him for his strength and the way he enjoyed a really good fight. What the teachers did with their tongues, he could do with his fists and feet and brute force. Anyone who wasn’t with him was against him – and your life was hardly worth living if you weren’t on his side – that is, until Jaspal came into the neighbourhood and soon formed a gang of his own.

Ever since Jaspal had moved into Whitworth Road, Johnnie had been out to get him; but though Jaspal was shorter than he, and thinner, somehow, Johnnie could never get to grips with him. He would no sooner jump on his back and get his head into a stranglehold, than Jaspal would wriggle like a fish, slither like a snake – somehow just make himself smaller and slip out of his grip. Other times, when the two boys would come face to face with each other, Jaspal’s body seemed to solidify. He would stand upright, calm and still, except that the muscles in his neck were as taut as rope and his limbs all ready to strike like a whiplash. Many a time, Johnnie had set the gang on him, but Jaspal was fast, elusive and cunning. No one could outrun him. It was as if he could make himself invisible.

‘Hanuman, Hanuman,’ whispered their mother when Marvinder told her from inside her head. ‘Hanuman, the son of Vayu, the god of the wind. He has magic powers – and not even the king of the demons can kill him. Hanuman found Sita. One day, he will find me.’

‘You’re like Hanuman,’ Marvinder whispered to her brother, when she watched a gang fight one day on the common. It had been a brutal, bloody fight, but Jaspal couldn’t be beaten. If he got knocked down, he was up on his feet again in a trice. He seemed to have eyes at the back of his head, and when his enemies came up behind him, he would start whirling his arms about and yelling like a mad creature.

Jaspal took up the name. He liked the sound it made. Hanuman . . . Hanuman . . . general of the king of the monkeys’ army, fighter of demons; son of the wind god with powers to make himself invisible, or turn himself into any shape both big and small. He taught the word to his gang. Now, when they went into a fight, they would chant, Hanuman . . . Hanuman . . . Hanuman . . . and before they had even struck a blow, the sound of the chanting brought fear into the hearts of Johnnie Cudlip and his gang.

‘Watching for the chuff-chuff, are we?’ Johnnie sneered. Jaspal was alone. Alone, he looked small, thin and easy to bully. Taking advantage of a break in the traffic, Johnnie dashed over the road and stood menacingly close to Jaspal.

The train was hurtling closer in a great cloud of black steam and smoke. Jaspal would have to lean well over to see the number. It meant turning his back on Johnnie. He hesitated then, gripping the rail of the bridge, he heaved himself up to his armpits and, with his toes, found some rivets with which to steady himself. He leaned over as far as he dared. The engine smoke whirled about him. Suddenly he felt hands grip his legs. Johnnie tipped him so that he was almost see-sawing over the side.

‘Need some help, do you?’ taunted Johnnie, laughing fiercely.

Jaspal felt himself losing control as the train sped beneath him, under the bridge. Instinctively, he clutched the sides with his hands and, in doing so, let slip his precious notebook, which contained pages and pages of numbers and the names of engines, taken down over hours of train-spotting. With a cry of anguish, he watched it fluttering down onto the track, just as the last carriage was sucked from view.

With miserable fury, Jaspal kicked out with all his might and sent Johnnie stumbling backwards, almost into the road. A bus blared out a warning on its horn, and someone shouted, ‘Bloomin’ rascals! Why aren’t they in school?’

Free of Johnnie’s grip, Jaspal ran to the far end of the bridge. All he could think about was retrieving his notebook. He discovered a small space between the edge of the bridge and a wall. He slid through and found himself on top of the steep embankment. There below him on the track he saw it, the wind idly riffling through its pages.

He began to slide down, partly on his bottom, struggling to keep control.

‘You coolie. I’ll get you for that!’ Smarting from the indignity of being kicked into the gutter, Johnnie came slithering down the embankment after him.

Jaspal reached the track. Just then, they heard another whistle. A second train was coming. If he didn’t get his notebook, it would be completely mangled beneath the wheels.

A goods train trundled into sight. It wasn’t as fast as the express, but it was going at a fairly swift speed. Jaspal didn’t hesitate. He dashed onto the line and grabbed the notebook. Johnnie too had now reached the edge of the track. Jaspal laughed and stood there, balancing on the rails brandishing his notebook. ‘Did you want something, beanpole?’ bellowed Jaspal. ‘Well, come and get it!’

The train driver was blasting a warning on his whistle. He was only fifteen metres away. Jaspal didn’t move. Johnnie made as if to run across. The driver blew his whistle again. Johnnie hesitated.

‘Cowardy custard, can’t eat mustard!’ yelled Jaspal triumphantly. Johnnie flinched with horror as Jaspal threw himself off the track, a couple of metres from impact with the train.

The two boys stared at each other between the passing trucks. Their gaze burned with enmity; then, before the long trail of goods had gone by, Jaspal had vanished.

That evening, Jaspal and his gang gathered in the cellar of the bombed house at the end of the road. They were initiating a new member into their brotherhood. Jaspal, as leader, stood on a table to give him height and authority. He wore a black turban and Indian shirt and pyjamas. His ceremonial sword was visible where it was tucked into his belt. He stood with his arms folded and feet apart, like a Sikh warrior waiting for action. Two candles flickered, casting gigantic shadows against the stone walls and the boys below him were quiet and attentive, their shadowed features turned upwards expectantly. They didn’t have turbans quite like Jaspal’s, but they wore bandanas round their heads whenever they gathered together.

He looked down on his followers – about eight of them – their faces solemn and dedicated. Two of the gang stepped forward, flanking a thin, pale-faced boy who was blindfolded. One of the gang removed the blindfold, while another gave him his spectacles. The boy hastily crammed the spectacles onto his face, which gave him a startled expression and made him look scared. He was new to the area and had been tormented at school. He knew that the only way to survive was to get into one of the gangs, then at least he would have the protection of his own gang brothers. He glanced around him nervously, then looked down.

‘What’s your name?’ demanded Jaspal.

‘Gordon Collins.’

‘To join this gang, you have to go through a test to prove you are brave and loyal. Do you understand?’ Jaspal stared at him coldly.

‘Yes.’ Gordon tried to control his quavering voice and he kept his eyes firmly to the ground. What would they ask him to do? He had heard stories of terrible tasks to get into gangs – things that were dangerous or terrifying. He waited with dread.

‘We have decided that you must spend the night in St Peter’s Church alone, and whatever happens – whatever you see or hear – don’t try and sneak out, because we’ll know, and not only will you be banned from our gang, but we’ll punish you for failing.’

Gordon heaved a sigh of relief, and looked round – his glance seeming to say, ‘Is that all?’ He thought they might ask him to run across the railway track in front of an oncoming train, or to walk across the wall of the canal bridge in the dark. But there was a general intake of breath and a low murmuring from the gang members, as if they thought this was bad enough.

‘When must I do it?’ he asked.

‘Tomorrow night,’ answered Jaspal. ‘Be outside the Palladium Cinema at ten o’clock sharp, and we will see you into the church. We’ll be waiting for you when you come out in the morning – so don’t think you can get away with anything. Understood?’

Gordon nodded. As he was escorted out of the cellar, he heard them chanting softly . . . Hanuman . . . Hanuman . . . Hanuman . . . They told him to scram. Until he was a gang member, he was not allowed to stay on for the meeting.

‘Cor! Wouldn’t like to be in your shoes,’ hissed his escort, at the top of the steps. ‘That church is haunted. I’ve heard of people who go grey with fright after spending a night in there.’

‘I don’t believe in ghosts,’ declared Gordon stoutly, hoping that his shaking voice didn’t give him away.

‘Huh! Tell us that the day after tomorrow!’ jeered the boys, pushing Gordon on his way.

‘Right,’ said Jaspal, jumping down from the table and sitting on it. ‘Business. The Johnnie Cudlip gang attacked Ronnie, Teddy and Frank in Warley Grove last night.’

Everyone turned and sympathetically examined the cuts and bruises of three younger boys who sniffed and wiped their noses across their sleeves and grinned sheepishly.

‘They’re cowards, that lot, picking on the little ones. Got no guts to face us. I think we need to show ’em. We must draw the whole Cudlip gang out; plan an attack – an ambush – and fight them into surrender. It’s about time Johnnie realised he can’t keep messing us about. I say we fight them after school . . . down at the tracks. Put out the word.’

FIVE

The Prisoner

It was Saturday. Maeve Singh came downstairs and stood in the doorway of her parents’ flat. Her body was still girlishly thin and undeveloped, as if she had grown up reluctantly. She held herself awkwardly stiff, like a tightly-coiled spring; her lips pressed together, her pretty face taut and defensive.

Her paper-white skin looked almost translucent as the sunlight fell across her face.

She was dressed to go out, though without much effort. She would have looked drab, except that the sun seemed to ignite the coils of red hair, which fell to her shoulders from beneath a panama-shaped green hat, and enriched the otherwise dull brown of her shapeless coat.

Her little daughter, Beryl, stood half-behind her, knee-high, clutching her mother’s coat in one hand, while sucking her thumb through a tight fist, with the other. She wasn’t dressed to go out, and knew that she was about to be left. Her light brown eyes shifted uneasily round the room, settling first on Jaspal, her half-brother. She was frightened of him. He always scowled and looked angry. He didn’t like her, she knew that. He hardly ever looked at her.

Marvinder was different. Beryl loved her. Marvinder seemed pleased to have a sister, even if she was only a half-sister. But Beryl would get used to being only half; half a sister, half-Indian, half-Irish . . . not as wholly Indian as their father, Govind, and not as wholly Irish as her mother, Maeve. Her skin was neither white nor brown; her hair neither black nor red. Only her eyes, her pale, flecked-brown eyes like the skins of almonds, were exactly the same as her father’s eyes and exactly the same as Marvinder’s. But she would not know this yet. She didn’t look in mirrors – at least not to assess herself. Her mirror was other people, and she saw herself the way they saw her.

‘Are you ready?’ Maeve asked. There was no enthusiasm in her voice.

Jaspal, Marvinder and Maeve’s young sister, Kathleen, had been lolling in front of the fire, engrossed in comics. Marvinder got up immediately, and pulled down her coat from the door, and Kathleen went over to her little niece, to coax her into staying. Jaspal rudely ignored Maeve and went on reading.

‘Well, come on then,’ Maeve was impatient. ‘Get your coat on, Jaspal. We’ll miss the bus. Good grief, we only go once a fortnight and, after all, it is to see your own father.’ She almost spat out the word ‘father’ like a bitter pill.

‘Can I go see Dadda!’ wailed Beryl.

‘Yeah, take Beryl. I don’t want to go,’ Jaspal muttered.

‘Come on, bhai,’ urged Marvinder, and she chucked his coat at him.

He reacted angrily. ‘Look what you’ve done, you stupid idiot!’ he yelled, dragging his comic out from under the coat. ‘That’s my comic. You’ve gone and wrecked my comic!’

Marvinder looked pained. Jaspal never used to talk rudely to her. ‘It doesn’t looked wrecked to me,’ she retorted. ‘Here!’ She reached out to straighten it, but he whipped it away.

‘Leave off. It’s mine.’

‘I know it’s yours, silly! I was just going to smooth it out.’

Maeve ran over impatiently and snatched at the comic. ‘For God’s sake, Jaspal, will you stop messing around and come. We’re going to miss the bus, I tell you.’

There was a ripping sound.

Jaspal gave a bellow of fury. ‘Look what you’ve done! You’ve torn it . . . you . . .’ He looked as if he would fly at her, but Marvinder grabbed his arm.

‘Jaspal, no!’ She begged, ‘Just put on your coat and come.’ She picked up his grey worsted coat and firmly held it out for him.

Jaspal snorted angrily and broke into a stream of Punjabi, which he knew infuriated Maeve. ‘Why should I do what that woman wants? She’s not my mother. She’s nothing but a thief and a harlot, stealing away our father. Now she thinks she can lord it over us. Well, she can’t. I don’t have to do anything she says.’

‘Oi, oi! You being rude again, you little devil?’ It was Mrs O’Grady appearing at the door. Her plump face was red with effort. She was panting heavily with having hauled two vast bundles of other people’s laundry up the long flight of stairs. ‘You needn’t think I don’t know what you’re saying, just because you speak in your gibberish.’ She dropped the washing and strode over to Jaspal with her hand raised. ‘You get your coat on immediately or you’ll get a clip round the ear.’ She hovered over him, threateningly. ‘And if I hear you’ve given Maeve any of your lip while out, Mr O’Grady will get his belt to you.’

That was no mean threat. One leg or no, Mr O’Grady was a powerful distributor of punishments, and even his strapping sons, Michael and Patrick, had to watch themselves when their father got mad.

Jaspal sullenly thrust his arms into the sleeves of the coat which Marvinder still held out for him, though when she tried to do up his buttons he pushed her away.

‘I’ll do it,’ he growled. ‘I’m not a baby.’

‘Huh, I’m not so sure about that,’ snapped Mrs O’Grady, lowering her hand. ‘Now get off with you,’ and she herded them to the landing, checking their hats and scarves and gloves and warning them about the chill out there.

If those who make up a family are like the spokes of a wheel, then Mrs O’Grady was both the hub and the outer rim. She held them all together; she fed them, nurtured them, washed and cooked for them and bullied them. She put up with her husband, with his drinking and temper and his fury at losing a leg in the war; she hustled her two boys, Patrick and Michael, making sure they got off to work every day – then taking half their wages at the end of the week, to store in the teapot which stood on the mantelpiece; and when Maeve had got pregnant by Govind – even though the man was a heathen and as brown as the River Thames, she insisted that the couple move into the household, taking the top-floor flat, which meant that the younger sister, Kathy, had to move down and sleep in the hall under the stairs.

In due course, when Beryl was born, it was Mrs O’Grady who coped, for Maeve was a reluctant mother, distraught at finding her freedom curtailed; and only a woman as mighty an Amazon as Mrs O’Grady could have endured the shock of finding out that Govind already had a wife and family back in India; only a woman with shoulders as broad as a continent could then take on his two refugee children, Jaspal and Marvinder, when they turned up out of the blue to find their father – a father who had got mixed up in black-marketeering and who was then sent to prison. She may have raged and grumbled and lashed out with her tongue, but she never complained. But kneeling in the darkness of the confessional, she had whispered to Father Macnally that she had prayed to the sweet Virgin not to send her any more children to look after – and especially, please – no more heathens.

‘Mum!’ Beryl wailed pathetically. She broke away from Kathleen’s arms and reached out for Maeve. ‘I want to see Dadda. Take me too!’

Mrs O’Grady snatched up her grandchild and held her firmly, ‘You stay with your Gran and your Aunty Kathleen, there’s a duck. You can go next time.’

‘We’ll see you later, Beryl,’ Maeve cooed at her child, trying to soften her voice and her face, before following Jaspal and Marvinder downstairs and out of the front door.

A sharp spring wind blew up Wandsworth High Road. It blew the scattered bus tickets into red, blue and yellow spirals and whirled them along the pavements. It made you hold on to your hat and clutch at your coat. It was the sort of wind which found its way into every crevice between neck and scarf, or wrist and glove. Even through the buttonholes. They bent their heads before it as they walked to the bus stop; and turned their backs on it, as they waited and waited for the red double-decker to come.

They were grateful to the wind. At least it gave them an excuse not to talk. Instead, they buried their reddened chins into their scarves and collars and gazed wistfully down the road, as if their very concentration could will the bus to come quicker.

And when it came, roaring to a stop in response to their outstretched hands, they always went clattering up the metal spiral steps onto the top deck. Maeve liked to smoke.

Jaspal and Marvinder would rush for the seats up at the very front above the driver’s head. They enjoyed the clear open view, and the feeling of being on top of the world. They could lean right forward and press their brows up against the glass.

But for all that, it was a gloomy journey which none of them relished. If only they could have got off at the river and spent the day in Battersea Park, or if, instead of changing buses at Hammersmith, they could have walked down to Shepherd’s Bush market and milled around the hustle and bustle of the stalls. Instead, they had to watch it all slide by and listen to the monotonous warnings of the conductor. ‘Hold very tight, please,’ as he tugged on the lower-deck bell string. ‘Ting, ting!’ It was one ting to stop and two tings to go.

At last they reached Ducane Road. The vast open playing fields of Latymer School seemed to gather up the winds and hurl them into their faces.

That final walk always seemed the longest. Maeve walked a little head, as if embarrassed by them, looking fixedly in front, never addressing any remarks to them, as if afraid people might think they were her children.

Two groups of people walked the same pavement, but managed to create a meaningful distance between each other.

There were those whose destination was Hammersmith Hospital, and with whom Maeve tried to merge for most of the walk. They were a generally cheerful lot, clutching bunches of newly-bought flowers from strategically-placed flower-sellers, or brown paper bags full of whatever fruit they could obtain with their ration coupons.

This group pretended not to see the other group, with whom, for a while, they shared the same pavement and the same direction. Their eyes looked through them as though they were ghosts, and there was a certain smugness, when this first group branched off and poured through the gates of the hospital in time for visiting hours.

The second group pretended not to notice or care. Their faces were grimmer, their pace more reluctant. Hardly anyone spoke, but concentrated on coaxing their children along, or simply fixing their focus on the next main gateway, to which they finally came. And when they walked through, they kept their eyes lowered to the ground. They never looked up at the grim fortress towers of His Majesty’s Prison, Wormwood Scrubs.

Here, Maeve, Jaspal and Marvinder joined a sizeable straggle of mostly women and children, gathering outside the large oval gate, waiting for the exact moment when they would be admitted. No matter how awful the weather, the gate was never opened even thirty seconds earlier than ordained.

Unlike hospital visitors, they weren’t allowed to take in flowers or fruit or packages of food. Each was frisked at the gate; handbags were opened and searched. They were made to feel that by visiting a prisoner, the visitor too was somehow guilty.

After further hanging about, they were all finally ushered into a large room, supervised by blank-faced warders, where, waiting for them at a series of tables, were the prisoners, their eyes eagerly scanning the faces as they came in.

Marvinder saw her father.

He was thinner these days. Perhaps it was the way they cropped his hair very close to the head; it seemed to emphasise his gaunt face; it made his cheeks look more hollow. His skin was blanched as if deprived of sunlight.

Lately, he had become withdrawn. Marvinder wondered whether it was to do with the killing of Mahatma Gandhi. When they broke the news to him a couple of months back, he looked as if he were going to faint.

‘Was he a very important man, Pa?’ she had asked, when he had collapsed into his chair and thrust his head down on the table between his arms.

‘Who can forgive me?’ was all her father had been able to choke, as if he had been the assassin.

‘When he was a student your father admired Mahatma Gandhi; worshipped him like a saint,’ Jhoti had explained inside her daughter’s head. ‘He travelled miles to attend his gatherings, and then came back to the village with such stories. He would tell us that the British were going to leave, and that India would become independent; how this little, half-starved man, with only a piece of cloth round his middle, was standing up to the might of the British Empire. The whole village would gather round to listen. Your father was such an important person in those days. But now . . . who would have thought . . .’

Marvinder waved a timid greeting. Her father raised a hand in acknowledgement. He stood up, but looked past her. He looked past Maeve too. It was Jaspal on whom he feasted his eyes. His gaze seemed to plead for understanding and forgiveness. ‘Can’t we be friends?’

But Jaspal lowered his eyes with embarrassment. It had been easy to love his father when he thought he was a hero. When they had lived in India, in their little Punjabi village, Jaspal, who had never known his father, grew up looking at the proud, flower-draped photograph, which had been taken when Govind graduated from Amritsar University. His turbaned head, with sleek moustache and confident eyes, stared out with a faint look of surprise, as though marvelling that he, the son of a simple farmer, could rise to such heights.