Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

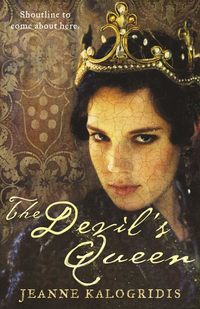

Kitabı oku: «The Devil’s Queen», sayfa 3

Three

I ran to the library and threw open the shutters to let in the sun and any sounds from the street or the stables near the gate. Then I found De Vita Coelitus Comparanda, written in the author’s script on yellowing parchment. Piero had left it on the bottom shelf so he could easily retrieve it, which allowed me to slide it off and guide it clumsily down to the floor.

I sat cross-legged, pulled the volume onto my lap, and opened it. I was far too agitated to read, but pressed my palms against the cool pages and stared at the words. I calmed myself by lifting a page, turning it, and smoothing it down with my hand. I turned another page, and another, until my breathing slowed, until my eyes relaxed and began to recognize a word here, a phrase there.

I had finally settled down enough to read when my eyes caught a flash of movement. Piero stood in the doorway, his cheeks flushed, his chest heaving. His face betrayed such misery and guilt I could not bear to look at him but lowered my gaze back to the book in my lap.

“I told them I couldn’t leave you,” he said. “If you can’t go, then I won’t.”

“It doesn’t matter what we want,” I said flatly. If I was in grave danger, then Piero was better off abandoning my company; the kindest thing I could do for him now was to be cruel. “I’m an heir and must remain. You’re not, so you must respect your mother’s bargain and leave.”

“They want Ippolito and Sandro, not you,” he persisted. “I’ll talk to Mother. They’ll see reason….”

I ran my finger down a page and said coldly, “It’s already decided, Piero. There’s no point in talking about it.”

“Cat,” he said, with such anguish that my resolve wavered—but I kept my gaze fixed on the page.

He stood in the doorway a bit longer, but I would not look up, not until the sound of his footsteps had faded.

I sat alone in the library until the sun passed midheaven and did not stir until a sound drew me to the window.

The coach bearing Piero, his brothers, and Uncle Filippo had rolled up to the gate and paused there while our soldiers moved aside to let the gate swing inward. As they did, two men walked through the opening onto our estate. Both were of noble birth; one wore a self-important air and an embroidered blue tunic. The other was dark and muscular, with a military commander’s bearing. Once they made their way past our guards, the man in blue signaled the carriage driver.

I stared, stricken, as the carriage rumbled through the gate and onto the street outside. There was no chance Piero could see me: The low sun created a blinding glare, and I could not see the windows of the carriage. Even so I waved, and watched as it headed north down the Via de’ Gori and disappeared.

At suppertime, Paola found me and shooed me to my room, where a plate of food awaited me. She also brought a talisman on a leather thong and hung it round my neck. I agreed to remain in my room in exchange for Ficino’s book, but before Paola could deliver it and leave, I pelted her with questions: What were the names of the two men at the gate? How long were they expected to stay?

She was overworked and exasperated, but I managed to tease from her the phrase “Niccolò Capponi, leader of the rebels, and his general, Bernardo Rinuccini.”

I obeyed her and kept to my room. After many hours of anxious reading, I fell asleep.

I woke to the sound of shouting and hurried to the main landing. In the foyer at the foot of the stairs, Passerini—in his scarlet cardinal’s gown trimmed with ermine, his ample jowls spilling over the too-tight neck—stood shouting, flanked by Ippolito and Sandro. The Cardinal had apparently drunk a good portion of wine.

“It’s an outrage!” he shrieked. “I am the regent, I alone possess the authority to make such decisions. And I denounce this one!” He stood inches from Aunt Clarice, who, accompanied by two men at arms, barred entry to the dining hall. “You insult us!”

He seized Clarice’s right wrist, wrenching it so violently that she cried out in surprise and pain.

“Worthless bastard!” she shouted. “Let go of me!”

On either side of her, the guards unsheathed their swords. Passerini dropped hold of her at once. The younger of the guards was ready to strike, but Clarice signaled for peace and caught Ippolito’s gaze.

“Get them from my sight,” she hissed.

Cradling her injured wrist, she turned and swept imperiously back into the dining hall. The door closed behind her, and the guards positioned themselves in front of it. The Cardinal lurched slightly, as if considering whether to charge the door, but Ippolito caught his arm.

“They’ve made the decision to deal with her,” he said. “There’s nothing we can do here. Come.” Still gripping Passerini’s arm, he moved for the stairs; Sandro followed.

I held my ground on the landing as they ascended toward me and looked questioningly at Ippolito.

“Our aunt has chosen to humiliate us, Caterina,” Ippolito said tautly, “by barring us from the negotiations at the request of the rebels. I’m sure they’ll find her more accommodating.” His voice grew very low and soft. “She has humiliated us. And she will pay.”

I watched as they made their way to their apartments, then I returned to my bed and stared at the window and the darkness beyond it, broken by the wavering glow from the rebels’ torches.

I slept fitfully, with dreams of men and swords and shouting. At dawn, sounds pulled me from sleep: the ring of bootheels on marble, the murmur of men’s voices. I called for Paola, who came and dressed me with a far rougher hand than Ginevra ever had. On her orders, I ran down toward the kitchen but stopped in the ground-floor corridor. The door to the dining hall was open; curiosity compelled me to peer past the threshold.

Clarice was inside. She sat alone at the long table littered with empty goblets; hers was full, untouched. She was dressed gorgeously in deep green brocade, and the train of her gown spilled over the side of the chair and pooled artfully at her feet. Her arm rested on the table, and her face, nestled in the crook, was turned from me. Her chestnut hair hung upon her shoulder, restrained by a gold net studded with tiny diamonds.

She heard me and languidly lifted her head. She was full awake, but her expression was lifeless; I was too young to interpret it then, but over the years I have come to recognize the dull look of undigested grief.

“Caterina,” she said, without inflection; her eyes were heavy-lidded with exhaustion. She leaned over and patted the seat of the chair beside her. “Come, sit with me. The men will be down soon, and you might as well hear.”

I sat. Her wrist, propped upon the table, was badly swollen, with dark marks left by Passerini’s fingers. Within a few minutes, Leda led Passerini and the cousins to the table. Ippolito’s manner was reserved; Passerini’s and Sandro’s, angry and challenging.

When they had taken their seats, Aunt Clarice waved Leda out of the room. Capponi had guaranteed us all safe passage, she said. We would go to Naples, where her mother’s people, the Orsini, would take us in. With their help, we would raise an army. The Duke of Milan would support us, and the d’Estes of Ferrara, and every other dynasty in Italy with sense enough to see that the formation of another Venice-style republic was an outright threat to them.

Passerini interrupted. “You gave Capponi everything he wanted, didn’t you? No wonder they preferred to deal with a woman!”

Clarice looked wearily at him. “Their men surround this house, Silvio. They have soldiers and weapons, and we have neither. With what did you intend me to bargain?”

“They came to us!” Passerini snarled. “They wanted something.”

“They wanted our heads,” Clarice said, with a faint trace of spirit. “Instead they will grant us safe passage. And in exchange, we must give them this.”

She spoke tonelessly and at length: The rebels would let us live, if, in four days, on the seventeenth of May at midday, Ippolito, Alessandro, and I went to the great public square, the Piazza della Signoria, and announced our abdication. We would then swear oaths of allegiance to the new Third Republic of Florence. We would also swear never to return. Afterward, rebel soldiers would lead us to the city gates and waiting carriages.

The cardinal swore and sputtered. “Betrayal,” Sandro said. The magician’s face rose in my imagination and whispered: One that threatens your life. They both fell silent the instant Ippolito rose.

“I knew Florence was lost,” he told Clarice, his voice unsteady. “But there are other things we could have purchased our safety with—properties, hidden family treasure, promises of alliances. For you to agree to humiliate us publicly—”

Clarice raised a brow. “Would you prefer the bite of the executioner’s blade?”

“I will not bow to them, Aunt,” Ippolito said.

“I kept our dignity,” Clarice countered; the tiny diamonds in her hairnet sparkled as she lifted her chin. “They could have taken our heads. They could have stripped us and hung us in the Piazza della Signoria. Instead, they wait outside. They give us a bit of freedom. They give us time.”

Ippolito drew in a long breath, and when he let it go, he shuddered. “I will not bow to them,” he said, and the words held a threat.

Four miserable days passed; the men spent them closeted in Ippolito’s chambers. Aunt Clarice wandered empty halls, as all of the house servants—except the most loyal, which included Leda, Paola, the stablehands, and the cook—had left. Beyond the iron gate, the rebels kept watch; the soldiers who had guarded our palazzo abandoned us.

By the afternoon of the sixteenth—one day before we were all to humble ourselves in the Piazza della Signoria—my room was stripped. I begged Paola to pack the volume of Ficino, but she murmured that it was a very big book for such a little girl.

That evening, Aunt Clarice prevailed upon us to have supper in one of the smaller dining rooms. Ippolito had little to say to anyone; Sandro, however, seemed surprisingly lighthearted, as did Passerini—who, when Clarice voiced her regret over leaving the family home in hostile hands, patted her hand, pointedly ignoring her bandaged right wrist.

The dinner ended quietly—at least, for Clarice, Ippolito, and me. The three of us retired, leaving Sandro and Passerini to their wine and jokes. I could hear them laughing as I headed back toward the children’s apartments.

That night, I dreamt.

I stood in the center of a vast open field and spied in the distance a man, his body backlit by the rays of the dying sun. I could not see his face, but he knew me and called out to me in a foreign tongue.

Catherine …

Not Caterina, as I was christened at birth, but Catherine. I recognized it as my name, just as I had when the magician had once uttered it so.

Catherine, he cried again, anguished.

The setting changed abruptly, as happens in dreams. He lay on the ground at my feet and I stood over him, wanting to help. Blood welled up from his shadowed face like water from a spring and soaked the earth beneath him. I knew that I was responsible for this blood, that he would die if I did not do something. Yet I could not fathom what I was to do.

Catherine, he whispered, and died, and I woke to the sound of Leda screaming.

Four

The sound came from across the landing, from Ippolito and Alessandro’s shared apartments. I ran toward the source.

Leda had fallen in front of the wide-open door onto all fours. Her screams were now moans, which merged with the song of bells from the nearby cathedral of San Lorenzo, announcing the dawn.

I ran up to her. “Is it the baby?”

Gritting her teeth, Leda shook her head. Her stricken gaze was on Clarice, who had also come running in her chemise, a shawl thrown around her shoulders. She knelt beside the fallen woman. “The child is coming, then?”

Again, Leda shook her head and gestured at the heirs’ room. “I went to wake them,” she gasped.

Clarice’s face went slack. Wordlessly, she rose and hurried on bare feet into the men’s antechamber. I followed.

The outer room looked as it always had—with chairs, table, writing desks, a cold hearth for summer. Without announcing herself, Clarice sailed through the open door into Ippolito’s bedroom.

In its center—as if the perpetrators had intended to draw attention to their dramatic display—a pile of clothes lay on the floor: the farsettos Alessandro and Ippolito had worn the previous night, atop a tangle of black leggings and Passerini’s scarlet gown.

I stood behind my aunt as she bent down to check the abandoned fabric for warmth. As she straightened, she let go a whispered roar, filled with infinite rage.

“Traitors! Traitors! Sons of whores, all of you!”

She whirled about and saw me standing, terrified, in front of her. Her eyes were wild, her features contorted.

“I pledged on my honor,” she said, but not to me. “On my honor, on my family name, and Capponi trusted me.”

She fell silent until her anger transformed into ruthless determination. She took my hand firmly and led me ungently back into the corridor, where Leda was still moaning on the floor.

She seized the pregnant woman’s arm. “Get up. Quick, go to the stables and see if the carriages have gone.”

Leda arched her back and went rigid; liquid splashed softly against marble. Clarice took a step back from the clear puddle around Leda’s knees and shouted for Paola—who was, of course, horrified by the revelation of the men’s departure and needed severe chastising before she calmed.

Clarice ordered Paola to go to the stables to see if all the carriages were gone. “Calmly,” Clarice urged, “as if you had forgotten to pack something. Remember—the rebels are watching just beyond the gate.”

Once Paola had gone on her mission, Clarice glanced down at Leda and turned to me. “Help me get her to my room,” she said.

We lifted the laboring woman to her feet and helped her up the stairs to my aunt’s chambers. The spasm that had earlier seized her eased, and she sat, panting, in a chair near Clarice’s bed.

In due time, Paola returned, hysterical: Passerini and the heirs were nowhere to be found, yet the carriages that had been packed with their belongings still waited. The master of the horses and all the grooms were gone—and the bodies of three stablehands lay bloodied in the straw. Only a boy remained. He had been asleep, he said, and woke terrified to discover his fellows murdered and the master gone.

In Clarice’s eyes, I saw the flash of Lorenzo’s brilliant mind at work.

“My quill,” she said to Paola, “and paper.”

When Paola had delivered them both, Clarice sat at her desk and wrote two letters. The effort exasperated her, as her bandaged hand pained her; many times, she dropped the quill. She bade Paola fold one letter several times into a small square, the other, into thirds. With the smaller letter in hand, Aunt Clarice knelt at the foot of Leda’s chair and took the servant’s cheeks in her hands. A look passed between them that I, a child, did not understand. Then Clarice leaned forward and pressed her lips to Leda’s as a man might kiss a woman; Leda wound her arms about Clarice and held her fast. After a long moment, Clarice pulled away and touched her forehead to Leda’s in the tenderest of gestures.

Finally Clarice straightened. “You must be brave for me, Leda, or we are all dead. I will arrange with Capponi for you to go to my physician. You must give the doctor this”—she held up the little square of paper—“without anyone seeing or knowing.”

“But the rebels …,” Leda breathed, owl-eyed.

“They’ll have pity on you,” Clarice said firmly. “Doctor Cattani will make sure that your child arrives safely in this world. We will meet again, and soon. Only trust me.”

When Leda, tight-lipped, finally nodded, Clarice gestured for Paola to take the other letter, folded in thirds.

“Tell the rebels at the gate to deliver this to Capponi immediately. Wait for his answer, then come to me.”

Paola hesitated—only an instant, as Aunt Clarice’s gaze was far more frightening than the prospect of facing the tebels—and disappeared with the letter.

After a long, anxious hour—during which I managed to dress myself, with Clarice’s help—Paola reappeared with news that Capponi would let Leda leave provided she was judged sincerely pregnant and about to give birth. This led to an urgent consultation between the women as to where the letter should be concealed, and how Leda should pass it to the doctor without detection.

Then, per Capponi’s instruction, Clarice and Paola helped the pregnant woman down the stairs to the large brass door that opened directly onto the Via Larga. I shadowed them at a distance.

Just outside the door, two respectful nobles waited; beyond them, rebel soldiers held back the crowd that had gathered in the street. The nobles helped Leda into a waiting wagon. Aunt Clarice stood in the doorway, her palm pressed against the jamb, and watched as they drove Leda away. When she turned to face me, she was bereft. She did not expect to see Leda again—a ghastly thought, since the latter had served Clarice since both were children.

We headed back upstairs. In my aunt’s carriage, I read the truth: The world we knew was dissolving to make room for something new and terrible. I had been sad, thinking I would be separated from Piero for a few weeks; now, looking at Clarice’s face, I realized I might never set eyes on him again.

Once in her room, Clarice went to a cupboard and retrieved a gold florin.

“Take this to the stableboy,” she told Paola. “Tell him to remain at his post until the fifth hour of the morning, when he must saddle the largest stallion and lead it out through the back of the stables, to the rear walls of the estate. If he waits there for us, I will bring him another florin.” She paused. “If you tell him the heirs have gone—if you so much as hint at the truth—I will throw you over the gate myself and let them tear you to shreds, because he just might realize he can tell the rebels our secret to save his skin.”

Paola accepted the coin but hesitated, troubled. “There is no chance—even on the largest horse—that we could make it past the gate—”

Clarice’s gaze silenced her; Paola gave a quick little curtsy, then disappeared. Her expression, when she returned, was one of relief: The boy was still there, happy to obey. “He swears on his life that he will tell the rebels nothing,” she said.

I puzzled over Clarice’s scheme. I had been told several times that I was to go to the dining hall no later than the fifth hour of the morning, because Capponi’s general and his men would be on our doorstep half an hour later to escort us to the Piazza. Whatever her plan, she intended to execute it before their arrival.

I watched as Paola arranged Clarice’s hair and dressed her in the black-and-gold brocade gown she had chosen to wear for our family’s public humiliation. Paola was lacing on the first heavy, velvet-edged sleeve when the church bells signaled terce, the third hour of the morning. Three hours had passed since daybreak, when I had discovered Leda huddled on the floor; three more would pass until the bells chimed sext, the sixth hour, midday, when we were to arrive at the Piazza della Signoria.

Paola continued her task, although her fingers were clumsy and shaking. In the end, Clarice was dressed and achingly beautiful. She glanced into the mirror Paola held for her and scowled, sighing. Some new worry, some problem, had occurred to her, one she did not yet know how to resolve. But she turned to me with forced, hollow cheer.

“Now,” she asked, “how shall we amuse ourselves for the next two hours? We must find a way to busy ourselves, you and I.”

“I would like to go to the chapel,” I said.

Clarice entered the chapel slowly, reverently, and I reluctantly followed suit, genuflecting and crossing myself when she did, then settling beside her on the pew.

Clarice closed her eyes, but I could still see her mind struggling with some fresh challenge. I left her to it while I wriggled, straining my neck to get a better view of the mural.

Clarice sighed and opened her eyes again. “Didn’t you come to pray, child?”

I expected irritation but heard only curiosity, so I answered honestly. “No. I wanted to see Lorenzo again.”

Her face softened. “Then go and see him.”

I went over to the wooden choir stall just beneath the painting of the crowd following the youthful magus Gaspar and tilted my head back.

“Do you know them all, then?” Clarice asked behind me, her tone low and faintly sad.

I pointed to the first horse behind Gaspar’s. “Here is Piero the Gouty, Lorenzo’s father,” I said. “And beside him, his father, Cosimo the Old.” They had been shrewdest, most powerful men Florence had known, until Lorenzo il Magnifico supplanted them both.

Clarice stepped forward to gesture at a small face near Lorenzo’s, almost lost in the crowd. “And here is Giuliano, his brother. He was murdered in the cathedral, you know. They tried to murder Lorenzo, too. He was wounded and bleeding, but he wouldn’t leave his brother. His friends dragged him away as he shouted Giuliano’s name. No one was more loyal to those he loved.

“There are those who aren’t there beside him but should have been,” she continued. “Ghosts, of whom you have not heard enough. My mother should be there—your grandmother Alfonsina. She married Lorenzo’s eldest son, an idiot who promptly alienated the people and was banished. But she had a son—your father—and educated him in the subject of politics, so that when we Medici returned to Florence, he ruled it well enough. When your father went away to war, Alfonsina governed quite capably. And now…we have lost the city again.” She sighed. “No matter how brightly we shine, we Medici women are doomed to be eclipsed by our men.”

“I won’t let it happen to me,” I said.

She turned her head sharply to look down at me. “Won’t you?” she asked slowly. In her eyes I saw an idea being birthed, one that caused the recent worry there to vanish.

“I can be strong,” I said, “like Lorenzo. Please, I would like to touch him. Just once, before we go.”

She was not a large woman, but I was not a large child. She lifted me with effort, trying to spare her injured wrist, just high enough so that I could touch Lorenzo’s cheek. Silly child, I had expected the contours and warmth of flesh, and was surprised to find the surface beneath my fingertips flat and cold.

“He was no fool,” she said, when she had lowered me. “He knew when to love, and when to hate.

“When his brother was murdered—when he saw the House of Medici was in danger—he struck out.” She looked pointedly at me.

“Do you understand that it is possible to be good yet destroy one’s enemies, Caterina? That sometimes, to protect one’s own blood, it is necessary to let the blood of others?”

I shook my head, shocked.

“If a man came to our door,” Clarice persisted, “and wanted to murder me, to murder Piero and you, could you do what was necessary to stop him?”

I looked away for an instant, summoning the scene in my imagination. “Yes,” I answered. “I could.”

“You are like me,” Clarice said approvingly, “and Lorenzo: sensitive, yet able to do what needs to be done. The House of Medici must survive, and you, Caterina, are its only hope.”

She smiled darkly at me and, with her bandaged hand, reached into the folds of her skirt to draw out something slender and shining and very, very sharp.

We returned to Clarice’s quarters, where Paola waited, and spent the next hour twisting silk scarves around jewels and gold florins. With Paola’s help, my aunt tied four heavy makeshift belts around her waist, beneath her gown. A pair of emerald earrings and a large diamond went into her bodice. Clarice helped Paola secure two of the belts on her person, then set aside one gold florin.

Then we sat for half an hour, with only Clarice knowing what awaited us. Prompted by a signal known only to her, Clarice picked up the gold florin and handed it to Paola.

“Take this to the boy,” she said. “Tell him to ready a horse and lead it through the stables and out the back, then wait there. Then you come to us at the main entry.”

Paola left. Aunt Clarice took my hand and led me downstairs to stand with her by the front door. When the servant returned, Clarice caught her shoulders.

“Be calm,” she said, “and listen carefully to me. Caterina and I are going to the stables. Stay here. The instant we leave, count to twenty—then open this door.”

Paola’s arms thrashed to free herself from Clarice’s grasp; she began to cry out, but my aunt silenced her with a harsh shake.

“Listen,” Clarice snarled. “You must scream loudly to get everyone’s attention. Say that the heirs are upstairs, that they are escaping. Repeat it until everyone rushes into the house. Then you can run out and lose yourself in the crowd.” She paused. “The jewels are yours. If I don’t see you again, I wish you well.” She drew back and gave the servant a piercing look. “Before God Almighty, will you do it?”

Paola trembled mightily but whispered: “I’ll do it.”

“May He keep you, then.”

Clarice gripped my hand. Together we ran the length of the palazzo, through the corridors and courtyard and garden until we were in sight of the stables. She stopped abruptly in the shelter of a tall hedge and peered past it at the now-unlocked iron gate.

I peered with her. On the other side of the black bars, bored rebel soldiers kept watch in front of a milling crowd.

Then I heard them, high and shrill: Paola’s screams. Clarice stooped down and pulled off her slippers; I did the same. She waited while all the men turned toward the source of the noise—then, when they all surged to the east, away from the gate, she drew in a long breath and ran west, dragging me with her.

We kicked up clouds of dust as we dashed past the heirs’ waiting carriage, past our own; the harnessed horses whinnied in protest. We came alongside the stables, then veered behind them, past the spot where I had lain after I learned Piero would leave me. There, next to the high stone wall, stood a saddled mount and an astonished boy—a wiry Ethiopian not much older than I, with a cloud of feather-light hair. Bits of straw clung to his hair and clothes. Like the horse’s, his eyes were wide and worried and white. The massive roan shied, but the boy reined it in with ease.

“Help me up!” Clarice demanded; the shouting out in the street had grown so loud he could barely hear her.

My aunt wasted no time with modesty. She hiked up her skirts, exposing white legs, and placed her bare foot in the stirrup. The horse was tall and she could not bring her leg over its withers; the boy gave her rump a mighty shove, which allowed her to scramble up into the saddle. She sat astride it, taking the reins in her good hand, and maneuvered the horse sidelong to the wall until her leg was pressed between the animal’s barrel and the stone. Then she pierced our young rescuer with her gaze.

“You swore on your life that you would tell the rebels nothing,” she said. It was an accusation.

“Yes, yes,” he responded anxiously. “I will say nothing, Madonna.”

“Only those who know a secret promise to keep it,” she said. “And there is only one secret the rebels would want to hear today. What might it be? They would not care about an absent stable master and his murdered grooms.”

His mouth fell open; he looked as though he wanted to cry.

“Look at you, covered in straw,” Clarice told him. “You hid because, like the others, you had heard too much, and they were going to kill you, too. You know where the heirs have gone, don’t you?”

Owl-eyed, he dropped his head and stared hard at the grass. “No, Madonna, no …”

“You lie,” Clarice said. “And I don’t blame you. I would be frightened, too.”

His face contorted as he began to weep. “Please, Donna Clarice, don’t be angry, please…. Before God, I swear I will not tell anyone…. I could have gone to the rebels, run to the gate and told them everything, but I stayed. I have always been loyal, I will be loyal still. Only do not be angry.”

“I’m not angry,” she soothed. “We’ll take you with us. Lord knows, if we don’t, the rebels will torture you until you speak. I’ll give you another florin if you tell me where Ser Ippolito and the others have gone. But first, hand me the girl.” She leaned down and held her arms out to me.

He was bony but strong; he seized me below the ribs and swung me like a bale of hay up into Clarice’s fierce clutches.

A wave of fear slammed against me. I endured it until it crested and faded, leaving everything still and silent its wake. I had a choice: to quail, or to harden.

I hardened.

At the instant the boy handed me to my aunt, I slipped the stiletto from its sheath, hidden in my skirt pocket. It sliced easily through the skin beneath the boy’s jaw, in the same grinning arc Clarice had drawn for me on her own throat, with her finger.

But I was a child and not very strong. The wound was shallow; he flinched and drew back before I could finish. With all my might, I plunged the weapon deeper into the side of his neck. He clawed at the protruding dagger and let go a gurgling shriek, his eyes bulging with furious reproach.

Clutching me, Clarice kicked the boy’s shoulder. He fell backward, still screaming while Clarice set me on the saddle in front of her.

I stared down at him, horrified and intrigued by what I had just done.

He’s going to die in any case, my aunt had said. But the rebels would torture him horribly, until he confessed, and then they would hand him over to the crowd. You can spare him that.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.