Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Jonathan Bate 2015

Jonathan Bate asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

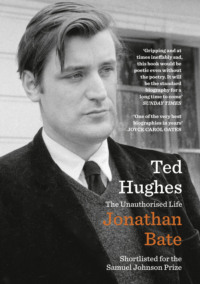

Cover photograph © John Hedgecoe/TopFoto

The author and publishers are committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others and have made all reasonable efforts to trace the copyright owners of the images reproduced, and to provide appropriate acknowledgement within this book. In the event that any untraceable copyright owners come forward after the publication of this book, the author and publishers will use all reasonable endeavours to rectify the position accordingly.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008118228

Ebook Edition © October 2015 ISBN: 9780008118235

Version: 2016-03-23

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Note to the Paperback Edition

Epigraph

Prologue: The Deposition

1. ‘fastened into place’

2. Capturing Animals

3. Tarka, Rain Horse, Pike

4. Goddess

5. Burnt Fox

6. ‘a compact index of everything to follow’

7. Falcon Yard

8. 18 Rugby Street

9. ‘Marriage is my medium’

10. ‘So this is America’

11. Famous Poet

12. The Grass Blade

13. ‘That Sunday Night’

14. The Custodian

15. The Iron Man

16. ‘Then autobiographical things knocked it all to bits, as before’

17. The Crow

18. The Savage God

19. Farmer Ted

20. The Elegiac Turn

21. The Arraignment

22. Sunstruck Foxglove

23. Remembrance of Elmet

24. The Fisher King

25. The Laureate

26. Trial

27. A

28. Goddess Revisited

29. Smiling Public Man

30. The Sorrows of the Deer

31. The Return of Alcestis

Epilogue: The Legacy

Notes

The Principal Works of Ted Hughes

Suggestions for Further Reading

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Index

Also by Jonathan Bate

About the Author

About the Publisher

Dedication

For Paula Jayne, again and always

And for Barrie and Deedee Wigmore,

because the shepherd’s hut unlocked it

Note to the Paperback Edition

I am most grateful to Anne Donovan, Peter Fydler, Brenda Hedden, Carol Hughes and Rowland Wymer for pointing out a number of errors, ambiguities and contested memories, which have been addressed in this edition.

Jonathan Bate, January 2016

Epigraph

As an imaginative writer, my only capital is my own life

Ted Hughes (1992)

When you sit with your pen, every year of your life is right there, wired into the communication between your brain and your writing hand … Maybe all poetry, insofar as it moves us and connects with us, is a revealing of something that the writer doesn’t actually want to say but desperately needs to communicate, to be delivered of. Perhaps it’s the need to keep it hidden that makes it poetic – makes it poetry. The writer daren’t actually put it into words, so it leaks out obliquely, smuggled through analogies … we’re actually saying something we desperately need to share. The real mystery is this strange need. Why can’t we just hide it and shut up? Why do we have to blab? Why do human beings need to confess? Maybe if you don’t have that secret confession, you don’t have a poem – don’t even have a story.

Ted Hughes, interviewed for The Paris Review (Spring 1995)

Prologue

The Deposition

Q. Would you state your full name for the record?

A. Edward James Hughes.

Q. What is your residence address?

A. Court Green, North Tawton 11, England.

Q. Have you a business address?

A. That’s it. I work from home.

Q. And what is your occupation, sir?

A. Writer.

The Yorkshire accent is unfamiliar. ‘Eleven’ is the stenographer’s mishearing of ‘Devon’. The date is 26 March 1986.

Q. And could you state your age for the record?

A. 55. I shall be 56 this year.

Q. Now, sir, were you at some time in your life married to a woman named Sylvia Plath?

A. Yes.

Q. Can you tell me when you first met her?

A. The 25th of February 1956.

Q. And where did you meet her?

A. Cambridge, England.

Q. And what were the circumstances of that meeting?

A. I met her at a party.

Q. Do you know what she was doing in England?

A. She was on a Fulbright scholarship.

Q. Do you know where she was from?

A. Did I know then?

Q. Yes.

A. I just knew she was American.

The details are established. Her home town was Wellesley, her college was Smith. And then:

Q. Do you know whether or not she had been ill?

A. She told me she had been ill later in the spring.

Q. Did she tell you she had been mentally ill?

A. She told me that she attempted to commit suicide.

Q. Did she tell you the circumstances of her having done that?

A. She only told me as an explanation of the scar on her cheek.

Q. Let me see if I understand your answer. There was a scar on her cheek, is that correct?

A. There was a big scar on her left cheek.1

The Deposition is being taken in the offices of Shapiro and Grace, attorneys, on Milk Street, Boston, before Josephine C. Aurelio, Registered Professional Reporter, a Notary Public within and for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Carolyn Grace, attorney, is acting on behalf of her client, Dr Jane V. Anderson, who is present in the room. Anderson is plaintiff in Civil Action number 82-0752-K, versus Avco Embassy Pictures Corporation and others, defendants. Edward James Hughes, writer, is one of the others.

He was a man who took astrology seriously. He believed in signs, auguries, meaningful coincidences. Often he would dream of something happening, only for it to happen subsequently. He lived by, and for, the power of words. His vocation was poetry, language wrought to its uttermost, words honed to their essence. The words of his poems – which he obsessively revised, refined, rewrote – are compacted, freighted with meaning, sometimes darkly opaque, sometimes cut like jewels of crystal clarity. He relished the resonance of names: Elmet, Moortown, the Duchy. He believed that houses held ghosts, strong forces, memories.

In Boston that March of 1986, walking familiar streets, he was flooded by memory. He and Sylvia had lived there some thirty years before, on:

Willow Street, poetical address.

Number nine, even better. It confirmed

We had to have it.2

Doubly poetical, in fact. There were the pastoral associations of willow: Hughes was haunted by the willow aslant the brook in Gertrude’s account of Ophelia’s suicide in Hamlet. More immediately, Hughes discovered that this had also once been the home of Robert Frost. Willow Street is just off Beacon Street, the heart of literary Boston. Here, a stone’s throw from the Charles River, you would find the offices of publishers, both established (Little, Brown) and independent (the Beacon Press). At number 10½ stood the Boston Athenaeum, the library at the centre of the New England intellectual life that back in the nineteenth century had set the template for the nation’s literature. For Ted Hughes, though, the name ‘Beacon’ was a call not only from the literary past but also from his Yorkshire home. His reading and his life came into conjunction. Which was something that seemed to happen to him again and again throughout his life.

The Yorkshire house, up on the hill, is called the Beacon. Square, rather squat, of dark-red brick, not the local gritstone that grounds those dwellings that seem truly to belong to the place. It stands, a little apart from its neighbours, on a long straight road at Heptonstall Slack, high above Hebden Bridge. It commands a sweeping view of hill and vale, down towards Lumb Bank, which would be another place of memory. This was the home of Ted Hughes’s parents when they returned to the Yorkshire Moors and the Calder Valley while he was at Cambridge University. A return to their roots, away from the unlovely town of Mexborough, further south, though still in Yorkshire, in the industrial area between Rotherham and Sheffield. Mexborough Grammar had been the school that prepared Ted Hughes for the Cambridge entrance examination.

The move to the Beacon was a sign of upward mobility. Edward James Hughes, like his elder brother and sister Gerald and Olwyn, was born and raised in a cramped end-terrace dwelling in the village of Mytholmroyd. In Mexborough, they had lived behind and above the newspaper and tobacco shop where William and Edith Hughes made their living. It was a matter of pride that they were eventually able to buy a detached house with a name and a view, just as it was a matter of pride that their boy Ted had got into Cambridge. They were not to know that he would rise even higher: that the boy from the end-terrace near the mill would fish privately with Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, talk of shamanism with a man born to become king and, just days before he died, receive from the hands of the Queen her highest personal honour, the Order of Merit.

The Beacon became a house of memory. It was here that Ted brought his bride, Sylvia Plath, to meet his parents in 1956. It was from here that he took Sylvia – playing Heathcliff to her Cathy – on a day trip to Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse believed to be the original of Wuthering Heights. It was here that the family gathered on the day that Sylvia was buried, near the family plot, just down the road in Heptonstall graveyard. It was here that he came at moments of crisis in later relationships: when he was thinking of buying Lumb Bank and making a home there with Assia Wevill and when he found himself having to choose between two women in 1970. It was to here that he and his sister Olwyn brought back their mother (‘Ma’) in the last days of her life and here that he came after seeing her cold body in the Chapel of Rest down in Hebden Bridge.

And it was here that he sometimes fought with Sylvia. ‘You claw the door,’ he wrote in a poem called ‘The Beacon’. The woman desperate to escape the house. Torrential Yorkshire rain crashes against the windowpanes. Inside the houses, on hillside and in valley, the lights of evening twinkle. ‘The Beacon’ gives a glimpse of Ted Hughes writing about domestic life. Yet it is also a poem of death, of graves and eternal silence. A beacon of memory, shining into the past. The memory of Sylvia among the Hugheses: chit-chat, telly, doing the dishes. Then a row, an explosion of anger. Sylvia, a trapped animal, brought fresh from the shining shore of the New World and confined in Yorkshire cold, Yorkshire grime, Yorkshire ways she does not really understand. She claws the door. Hughes at his most characteristic was a poet of claws and cages: Jaguar, Hawk and Crow. A poet who turns event and animal to myth.

Yet he was also a poet of deep tenderness, of restorative memory. If ‘The Beacon’ shines the light of memory into the past, there is another light that reaches forward with hope to the future, to redemption. In perhaps the greatest of his later poems, he calls it ‘a spirit-beacon / Lit by the power of the salmon’. This other beacon is found in an epiphanic morning moment when he stands waist-deep in pure cold Alaskan river water with his beloved son Nicholas. Here the ‘inner map’ of wild salmon becomes the cartography of Hughes’s own life: smoke-dimmed half-light of Calder Valley and wartime memory of ‘the drumming drift’ of Lancaster bombers. ‘Drumming’ had been one of Hughes’s signature words ever since the ‘drumming ploughland’ of ‘The Hawk in the Rain’, title poem of his first volume.

The poem is called ‘That Morning’.3 Even a word as seemingly flat as ‘that’ is often full of resonance in Hughes: not any morning, but that morning, that magical, memorable, poetical, immortal morning. The poem ends with a redemptive couplet that rhymes with itself: ‘So we stood, alive in the river of light / Among the creatures of light, creatures of light.’4 It is a poem about life at its best not only because Hughes is doing something that he loves in a location that is utterly sublime, but above all because he is together (‘we stood’) with his only son, who lives on the other side of the world. It is a poem full of heart, of love. A few years later Ted would urge Nick to ‘live like a mighty river’. ‘The only calibration that counts’, he wrote in a magnificent letter following another fishing trip, ‘is how much heart people invest, how much they ignore their fears of being hurt or caught out or humiliated. And the only thing people regret is that they didn’t live boldly enough, that they didn’t invest enough heart, didn’t love enough. Nothing else really counts at all.’5

The closing couplet of ‘That Morning’ is now inscribed on Ted Hughes’s memorial stone in Poets’ Corner. The national literary shrine in Westminster Abbey is indeed the place where England’s last permanent, as opposed to fixed-term, Poet Laureate in one sense belongs. But his spirit was only at peace in moorland air or when casting his rod over water, so it is fitting that his ashes are not there in the Abbey. Their place of scattering is marked by another stone, far to the west of his England.

Ted Hughes is our poet of light, but also of darkness. Of fresh water but also of polluted places. Of living life to the full, but also of death. And among his creatures are those not only of light but also of violence. We must celebrate his ‘dazzle of blessing’ but we cannot write his life without being honest about the ‘claw’, without confronting what in ‘That Morning’ he calls the wrong thoughts that darken.

In view of Hughes’s supernatural solicitings and given all the associations of the name Beacon, it was with grim satisfaction that, in the matter of Jane Anderson versus Avco Embassy Pictures and others, he found himself represented by Palmer and Dodge, working in conjunction with Peabody and Arnold, counsel for the lead defendant (Avco). These were two of Boston’s oldest and most respected law firms. Both had their premises at the auspicious address of 1 Beacon Street.

It was there on the morning of Thursday 3 April 1986, a week after Ted had made his Deposition, that Alexander (Sandy) H. Pratt Jr, acting on behalf of the defendants, asked some questions of Dr Anderson. Mr Pratt: ‘You felt, I take it, that Sylvia Plath wrote what she wrote in the book about the character Joan Gilling because she was hostile and angry towards you?’

Ms Grace: ‘Objection.’

Mr Pratt told Jane Anderson that she could answer. She replied, hesitantly: ‘I wouldn’t say – I would say that one of the reasons that she wrote what she wrote was – again, this is a hypothesis – but that she had some angry feelings towards me.’

Why was she angry? Because, said Anderson, of what took place when she visited Sylvia Plath in Cambridge, England, on 4 June 1956.6 That is to say, just over three months after Sylvia first met Ted Hughes ‘at a party’ and just twelve days before she married him in a swiftly arranged private ceremony in London. So what had happened at the meeting?

Sylvia Plath started talking in a very pressured way. That was my perception, that it was pressured. She said that she had met a man who was a poet, with whom she was very much in love. She went on to say that this person, whom she described as a very sadistic man, was someone she cared about a great deal and had entered into a relationship with. She also said that she thought she could manage him, manage his sadistic characteristics.

Q. Was she saying that he was sadistic towards her?

A. My recollection is she described him as someone who was very sadistic.7

Jane Anderson and Sylvia Plath had dated the same boys and had been fellow-patients in the McLean Hospital, New England’s premier mental health facility. By the time of the Deposition, Anderson herself had become a psychoanalyst. On the basis of what she had seen of Plath during her treatment at McLean following a suicide attempt, it was her judgement that Plath had not worked through her own feelings of anger regarding her father. Jane had told Sylvia that she was not taking her psychotherapy sufficiently seriously. In the light of this earlier history, Anderson had grave doubts about the wisdom of Plath entering into a relationship with a ‘very sadistic’ man. She did not actually counsel Sylvia against going ahead with the relationship, but, thinking about it on the train back to London, she sensed that she had created anger in Plath precisely because Plath was herself anxious and ambivalent about committing herself to Hughes.

How did it come to pass that Hughes and Anderson found themselves making these Depositions over twenty years after Plath’s suicide in the bitter London winter of 1963?

After the event, Ted Hughes’s lawyer summed up the issue at stake: ‘The plaintiff, Dr Jane Anderson, asserted that a character in the novel, The Bell Jar, and in the motion picture version was “of and concerning” herself, and that the portrayal of that character as a person with at least homosexual inclinations and suicidal inclinations defamed her and caused her substantial emotional anguish.’8 Reporting the first day of the trial, which finally came to court nearly a year after the Depositions, the New York Times put the case more dramatically:

Literature, lesbianism, psychiatry, film making, television and video cassettes were all touched upon in United States District Court today as a $6 million libel suit opened here … The defendants include 14 companies and individuals, including Avco Embassy Pictures, which produced the 1979 film derived from the novel; CBS Inc., which broadcast it twice; Time-Life Films, the owner of Home Box Office, which played it nine times; Vestron Inc., which made and distributed a video cassette of the film, plus the director and screen writer of the film … At the defendants’ table sat Ted Hughes, the poet laureate of England and a major defendant in the case.9

Many events in Ted Hughes’s eventful life have a surreal quality about them, but none more than this: Her Majesty’s Poet Laureate sits in a court room in the city of the Boston Tea Party, as defendant in a $6 million libel action against a film of a book that he did not write.

The full circumstances of the case, and its central significance in the Ted Hughes story, will be discussed later.10 What is particularly fascinating about his Deposition is that it provided the occasion for one of Hughes’s most forthright statements about what he considered to be the fallacy of biographical criticism. One reason why Jane Anderson had a good chance of winning her case, provided she could show that the character of Joan Gilling was indeed a ‘portrait’ of her, was that the first American edition of The Bell Jar, published posthumously in 1971, included a note by Lois Ames, who had been appointed by Ted and Olwyn Hughes as Sylvia Plath’s ‘official biographer’. The Ames note stated explicitly that ‘the central themes of Sylvia Plath’s early life are the basis for The Bell Jar’ and that the reason she had published it under a pseudonym in England shortly before her death (and not attempted to publish it at all in the United States) was that it might cause pain ‘to the many people close to her whose personalities she had distorted and lightly disguised in the book’.11

The name of Sylvia Plath has become synonymous with the idea of autobiographical or confessional literature. Teachers have a hard time persuading students that the character of Esther Greenwood in The Bell Jar, working as an intern at a New York fashion magazine, is not quite synonymous with Sylvia Plath working for Mademoiselle in June 1953 (‘a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs’).12 Or, indeed, that her most famous and infamous poem ‘Daddy’ is not wholly ‘about’ Sylvia’s relationship to her father Otto and her husband Ted – who habitually wore black, the colour of the poem.

‘Do you remember disagreeing with any aspect of the biographical note?’ Carolyn Grace asked Hughes. He had expected her to be a brisk, hard-edged feminist but found her more like a plump, slow-moving tapir, surprisingly sympathetic. After the Deposition was completed, they had a friendly chat – she told him that she had studied under the famous critic Yvor Winters, who had said how much he admired Ted’s poetry. Hughes, with characteristic self-deprecation, assumed that she had misremembered and that the poet whom Winters really admired was his friend Thom Gunn. In the late Fifties, they had been the two rising stars, the twin angry young men in the English poetic firmament.

A. I thought the whole thing was unnecessary.

Q. What was unnecessary?

A. Well, I thought by touching, attaching it so closely to Sylvia, it merely encouraged the general dilution that the book was about Silvia’s life, it was a scenario from Silvia’s life.

The court reporter is erratic in her spelling of Sylvia’s name and has, in an almost Freudian slip, misheard ‘delusion’ as ‘dilution’.

Q. Which you disagreed with?

A. Which I disagreed with.

Q. What was the basis for your disagreement, sir, that the book was a scenario of Silvia’s life?

A. The turmoil that I’ve had to deal with since Sylvia died was of every one of her readers interpreting everything that she wrote as some sort of statement about her immediate life; in other words, trying to turn this symbolic artist, really [brief gap in transcription] That’s why she’s so famous, that’s why she’s a big poetic figure: because she’s a great symbolic artist.

It is unfortunate that Hughes’s exact words are lost to the record here, but it is clear what he was arguing: that Plath was a symbolic artist persistently misread as a confessional one. He went on to explain:

My struggle has been with the world of people who interpret, try to shift her whole work into her life as if somehow her life was more interesting and was more the subject matter of debate than what she wrote. So there’s a constant effort to translate her works into her life.

Q. And you object to that?

A. It seems to me a great pity and wrong.13

At the time of the Bell Jar lawsuit, Ted Hughes was battling with Sylvia Plath’s biographers – as he battled for much of his life after her death.

Hughes was prepared for this line of questioning. The day before making his Deposition he had phoned Aurelia Plath, Sylvia’s mother. By one of the coincidences typical of Hughes’s life, Aurelia was preparing to give a lecture in a high school later that week on the very subject of how non-autobiographical her daughter’s novel was. Aurelia was ferociously bitter about the autobiographical elements in her daughter’s work. People had accused her of destroying Sylvia and Ted’s marriage, simply on the basis of Plath’s portrayal of her in the enraged poem ‘Medusa’ in her posthumously published collection, Ariel:

You steamed to me over the sea,

Fat and red, a placenta

Paralysing the kicking lovers.14

The conceit of the poem is that ‘Medusa’ is the name not only of the monstrous gorgon in classical mythology but also of a species of jellyfish of which the Latin name is Cnidaria Scypozoa Aurelia. Mother as love-murdering jellyfish: no wonder Aurelia wanted to play the ‘non-autobiographical’ card.

The trouble was, there had been a clause in paragraph 12 of the agreement between the Avco Embassy Pictures Corporation and the Sylvia Plath Estate (that is, Ted Hughes, represented by his agent, Olwyn Hughes) prohibiting any publicity that referred to the film of The Bell Jar as autobiographical. But somehow this clause had been deleted, in an amendment signed by Ted. Letting this go through was a fatal slip on Olwyn’s part. That is why he felt vulnerable in the case, despite the fact that he had in no sense authorised the offending lesbian scenes in the movie. After the awkward fifteen-minute phone call to Aurelia, he agonised with himself in his journal.

Nobody could deny that The Bell Jar was centred on Sylvia’s breakdown and the trauma of her attempted suicide. Hughes accordingly reasoned that he would have to argue that it was a fictional attempt to take control of the experience in order to reshape it to a positive end. By turning her suicidal impulse into art, Sylvia was seeking to save herself from its recurrence in life: she was trying ‘to change her fate, to protect herself – from herself’ but as an ‘attempt to get the upper hand of her split, her other personality, to defeat it, banish it, and, in the end, extinguish it’ it was ultimately a failure.15 The notion of the ‘split’ or ‘other personality’ in Plath was something to which Hughes returned again and again; it was also an obsession of Plath herself, already manifest in her 1955 undergraduate honours thesis at Smith, which was entitled ‘The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky’s Novels’. But these were deep matters, subtle distinctions that would not be easy to make in court. That night, Ted ate swordfish and went to bed early, readied for the encounter with Anderson’s lawyer the following day. In the morning he awoke to the newspaper headline ‘War with Ghaddafi’. His own literary-legal battle was about to begin.

Even as he was resisting the equation of art and life, Hughes was writing (though not publishing) poetry of unprecedented candour about his marriage to Sylvia. The Boston Deposition was a way-station on the road to Birthday Letters, the book about his marriage to Sylvia which he finally published in January 1998. In courtroom and hotel room, he followed Sylvia’s example of turning life into art by transforming the saga of the Bell Jar lawsuit into a long poem, divided into forty-six sections, still unpublished today, called ‘Trial’.

He wrote to his lawyer, to whom he had grown very close, directly after the trial: ‘The whole 24 year chronic malaise of Sylvia’s biographical problem seems to have come to some sort of crisis. I’d say the Trial forced it.’16 Or rather, he added, the synchronicity of the trial and his dealings with Plath’s biographers, of whom there were by that time no fewer than six.

Sylvia Plath’s death was the turning point in Ted Hughes’s life. And Plath’s biographers were his perpetual bane. In a rough poetic draft written when a television documentary was being made about her life, he used the image of the film-makers ‘crawling all over the church’ and peering over Sylvia’s ‘ghostly shoulder’. For nearly thirty years, Hughes and his second wife Carol lived in Court Green, the house by the church in the village of North Tawton in Devon that Ted and Sylvia had found in 1961. Their home was, he wrote, Plath’s mausoleum. The boom camera of the film-makers swung across the bottom of their garden. It was as if Ted and Carol were acting out the story of Sylvia on a movie set, their lives ‘displaced’ by her death.

The documentary crew crawled all over the yew tree in the neighbouring churchyard. Ted wryly suggests that if the moon were obligingly to come out and take part in the performance, they would crawl all over it. Both Moon and Yew Tree had been immortalised in Plath’s October 1961 poem of that title: ‘This is the light of the mind, cold and planetary. / The trees of the mind are black. The light is blue.’ In the documentary, broadcast in 1988, Hughes’s friend Al Alvarez, who played a critical part in the story of Sylvia’s last months, argued that this poem was her breakthrough into greatness.17

Sylvia’s biographers kept on writing, kept on crawling all over Ted. He compares them to maggots profiting at her death, inheritors of her craving for fame: ‘This is the audience / Applauding your farewell show.’18 Hughes was interested in both the theatricality and the symbolic meaning of Plath’s moon and yew tree, whereas the biographers and film-makers worked from a crudely literal view of poetic inspiration. His distinction in the Deposition between the ‘symbolic’ and the autobiographical artist comes to the crux of the matter.