Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

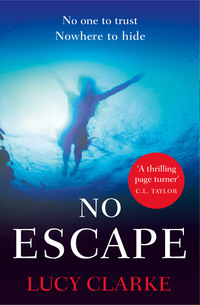

Kitabı oku: «No Escape», sayfa 3

4

NOW

Lana paces through her apartment, her fingers buried deep in the pockets of her dress. The painting she was working on is drying, unfinished. On a normal day, she would be getting ready for work by this time. But she can’t even think about going into the gallery and making coffees for customers. She can’t think of anything but The Blue.

She knows that the Maritime Rescue Centre, which will be dealing with the rescue of the crew, is only 30 kilometres away – she passes the sign for it each month when she goes to the art supplies wholesaler for her boss. She grabs her mobile and searches the Internet for the number.

When she finds it, she sits on the edge of her bed and makes the call. It takes several minutes to be connected to anyone associated with the rescue of The Blue. Eventually she is transferred to Paul Carter, the Operations Coordinator, who has a broad New Zealand accent and tells her that they are not at liberty to give out any details.

‘Look,’ she says, banging the heel of her hand against the wooden bed frame, making a dull thud. ‘Just tell me if Kitty Berry was on board. She’s British. She’s got no family out here. I can get in touch with them.’

Lana doesn’t know where the authority in her tone has sprung from, but she knows she will not be ending this call until she has an answer.

After a moment she hears the sigh of someone acquiescing. ‘Okay, give me a minute.’

As she waits, she bites the edge of her thumbnail, her skin tasting faintly of turpentine. She finds herself thinking of the first time she met Kitty. They were eleven years old and the summer term had just begun. Lana was grateful for the warmer weather because it meant that at lunchtimes she could sit alone in a sunny corner of the playing fields, and didn’t need to stand around in the courtyard trying to make herself look invisible. She’d take out her exercise book and fill the back pages with wild shapes – swirls of smoke, twisting currents of water, clouds that billowed and bloomed from the pages.

She had seen Kitty around – they lived in the same street and took the same bus to school – but they’d never spoken. Kitty styled her glossy dark hair in a high ponytail, pulling thin wisps of it loose around her temples. She was often followed around by a loud group of boys who wore their backpacks so low that they bounced against their bony arses.

Lana had been sitting cross-legged, watching a feathery seed from a dandelion drifting towards her on a whisper of breeze. She was mesmerized as it turned through the air, daylight catching in its white softness. She wondered what it would feel like to be that weightless. She reached a hand up into the air and caught it gently in the palm of her hand, imagining its tickle against her skin. Then she closed her eyes and made a wish. She wasn’t sure that you were meant to wish on dandelions, but she’d done it anyway.

When she opened her eyes, she carefully unfurled her fingers and – for a moment – it rested right there on the centre of her palm, as if she had tamed it. A few seconds later it lifted off, carried upwards on a current of air.

‘What you doing?’ Kitty was standing nearby, her school bag hanging off one shoulder.

‘Making a wish,’ she said. She felt her cheeks flush, cross that she’d not thought of something better than the truth.

‘What did you wish?’

‘You can’t tell people, otherwise they don’t come true.’

Kitty shrugged. Then she bent down and plucked a dandelion from the long grass near the fence line and held it up to her lips. ‘You can tell the time by blowing a dandelion. Watch.’ She blew with short puffs of air, making the seeds whirl. By her sixth puff there was only one seed remaining. Kitty adjusted her puffs so they became gentle, until her twelfth one – when she blew with all her might, sending the remaining seed dancing into the sky.

‘That was twelve.’ She pushed her wrist in front of Lana to reveal her purple watch. ‘Twelve o’clock. See?’

Lana laughed.

Kitty’s brow dipped. ‘What? It’s true.’

‘All right.’

They were both silent and Lana wished she hadn’t laughed, thinking Kitty was going to leave now. But after a minute or so, Kitty said, ‘So why d’you always sit on your own?’

Lana watched a ladybird crawl up a blade of grass near her feet, making the blade tremble and bend. ‘I dunno. Why are you on your own?’

‘I’m not. I’m talking to you.’ Kitty shook her head a little, making her high ponytail swing. Lana wondered whether Kitty was wearing mascara as her eyelashes looked so dark and long. Lana had her father’s eyelashes – auburn and short – as well as his amber hair. But her long, straight nose and olive skin came from her mother. People often remarked upon Lana’s unusual colouring, and she liked telling them, My father’s a redhead, but my mother was Greek.

‘Anyway, I’m looking for daffodils,’ Kitty announced.

‘How come?’

‘It’s my mum’s birthday today.’ Kitty looked at her from the corners of her eyes, then added, ‘She’s dead though.’

Lana stared back. With their gazes pinned to each other, she found herself saying, ‘Mine, too.’

If Kitty had been surprised, she hadn’t shown it. ‘My mum died when I was seven. Cancer. How old were you?’

‘Three.’

Lana told Kitty about the car accident. Even though she hadn’t been with her mother, the events of the day felt imprinted on her as if she’d lived through every frame. It was a Thursday morning; her mother was driving to the supermarket when a lorry hurtling along in the other direction had braked hard to avoid a car that pulled out in front of it. The lorry began jackknifing across the road. Tons of metal swung into Lana’s mother’s Renault 5, killing her on impact.

When other people heard what had happened to Lana’s mother, their expressions filled with pity and they spoke to her in a soft, special voice. But not Kitty. She listened with her head tilted to one side, her eyes locked on Lana.

After a moment Kitty said, ‘My mum died in a hospice. On her own. My dad was sitting in our car, smoking, and I was trying to find somewhere to change a pound coin so I could get a drink from the vending machine. When I came back to her ward, a bed sheet was pulled over her face.’

The two girls eyed one another in silence. Then Lana stood, picked up her bag and said, ‘Come on. I’ll show you where the best daffodils are.’

*

From the other end of the phone line Lana hears the man speak, the receiver pressed close to his mouth. ‘Yes,’ he says. ‘Kitty Berry is on the crew list.’

Lana’s heart clenches tight as a fist, her eyes squeezing shut.

So Kitty has still been on the yacht after all these months. After everything that had happened, Lana wonders if Kitty could still enjoy lying back in the hammock, watching the shooting stars blaze across the sky as they’d once done together.

She runs the heel of her hand back and forth across her forehead. ‘What happened out there? How did the yacht get into trouble?’

‘I’m not able to disclose any information just yet,’ Paul Carter says.

Lana grits her teeth with frustration. ‘Have you found her? Found any of them?’

There is a pause in which she hears the man clearing his throat. ‘I’m sorry. The entire crew is missing.’

*

Lana puts down the phone and remains sitting on the edge of the bed. It is almost impossible to picture The Blue somewhere out there in these waters. Sunk.

There was a life raft, she knows. It was stored in a canister at the stern, which she’d sometimes lean against, her legs stretched out in the sun. She wonders when the raft was last checked, and whether the grab bag was properly stocked, too.

She can picture the yacht easily – the teak deck warm beneath the soles of her feet; the white mainsail billowing with wind; the light slosh and draw of waves against the hull as the yacht turns lazily on its anchor. But she cannot bring to mind that same yacht struggling in the ocean as water washes on board, creeping down the hatch into the saloon where they all used to sit together for dinner. She cannot picture the sea steadily rising up over the floor, enveloping the lockers and cupboards stocked with food, blankets, torches and ropes, then creeping higher, bleeding over the photos pinned to the saloon wall and flooding the shelves of well-thumbed books. She cannot imagine the crew wading through salt water, while sodden charts, packets of food, loose clothes and toiletries float around them.

A yacht like that just doesn’t sink. It was built to handle the open ocean, rough seas. What the hell happened?

Lana raises herself to her feet and crosses the room to the window.

For months Lana tried her best to distance herself from the yacht and crew. She closed a door of her mind because behind it lay a beautiful, bright pain – and even opening it a crack seared. In some ways, she’s succeeded. She made a fresh start here in New Zealand, yet there are moments – if she catches sight of the swoop of a sail on the horizon, or hears a wave breaking onto the shore – then The Blue sails back into her thoughts. Sometimes all it takes to remember is a shopkeeper’s lilting accent, which sends Denny spiralling into her mind, or the sight of two friends walking with their heads pressed together, making her miss Kitty with a deep ache.

Now that she has heard this news, it feels as though each of the memories she has hidden away is unwinding, link by link, like an anchor chain dragging her downwards. She feels the weight of each memory pulling her deeper: thick fingers gripped around the pale skin of a throat; Shell’s tear-stricken face as she stepped forward at the bow to speak; dark waves lashing at the deck as the rigging shrieked in the wind; Kitty’s hollow-eyed gaze as she raised her hand into the air; the deep-red bloom of blood that stained the deck.

Back then, if Lana had known everything she does now, she wonders whether she’d ever have set foot on The Blue.

5

THEN

Lana stood at the helm, her hands resting on the sun-warmed wheel. A glowing red sun was lowering itself towards the sea, washing the water pink.

She turned to Kitty, whose skin looked a deep bronze in the evening light, the lenses of her sunglasses reflecting the fire of the sunset, and said, ‘I can’t help thinking that at any moment someone’s going to come along and tell us we’re in the wrong place.’

‘I know,’ Kitty agreed. ‘We’re out here sailing a fucking yacht together! Life doesn’t get much better, does it?’

This would be their fifth night on board The Blue, and they’d both fallen hopelessly in love with every aspect of it: the long hours spent snorkelling over coral gardens and exploring empty coves where wild mangoes grew; learning how to handle the sails and steer a course; cooking meals in the narrow galley kitchen with the view of the sea through the porthole; talking on deck until the early hours with rum warm in their throats.

‘Listen to this,’ Kitty said, lifting her hands towards Lana’s ear and rubbing her palms together. They made a rough scraping sound where the skin had become dry and callused from hauling the ropes – or sheets as Aaron had taught the girls to call them. ‘That’s my body’s way of telling me I’m not cut out for manual work. I’m going to see if Shell’s got any moisturizer.’

Kitty disappeared below deck, and Lana turned her attention to the plotter screen, checking their course and position. They were sailing to a small island Aaron had noticed on the charts, where they planned to anchor for the night. Aaron had a nose for searching out secluded bays and sheltered nooks of the coastline, preferring the adventure of discovering somewhere new rather than mooring up in a marina with the yachting crowd.

Two nights ago they’d anchored on the lee side of a tiny island that had just sixty inhabitants. Almost as soon as they’d dropped anchor, a dozen village kids swam out to the yacht. Aaron invited them on board and they’d stood dripping wet at the stern, smiling shyly and giggling. Denny had fetched a bag of sweets and within a few minutes the kids were exploring the yacht. They were mesmerized by the computer, the array of books in the saloon, and the music that played from Shell’s iPod.

Lana was beginning to gain an understanding of how the yacht moved. It was less reactive than a car, with adjustments taking longer, so when she turned the wheel one way it took a few seconds for the boat to follow. It was a strange sensation to steer from the back of a vessel and she kept pushing herself up onto tiptoes, peering over the bow to check the way was clear.

Aaron came up on deck holding an apple in his wide palm. He stood beside her, slipping a knife from the sheath that was fixed to the console. It was housed there for emergencies, like cutting a trapped line, or to protect themselves should they ever be boarded. Aaron wiped the blade against his shorts, then carefully sliced the first curve of the apple, lifting it to his mouth on the blade edge.

‘How you going?’ Aaron asked, as he crunched through the crisp flesh of the fruit.

‘Good, I think. We’ve been averaging about six to seven knots.’

He nodded, then didn’t say anything for some time. He watched the water, a peaceful expression settling into his features and softening the deep grooves that lined his forehead.

She wondered how old Aaron must be. The rest of the crew were in their twenties – Shell being the baby of the group at twenty-two – but Aaron seemed more life-worn: in his early thirties perhaps. It was still a young age to own a yacht the size of The Blue. Even though the yacht wasn’t one of the modern, expensive new models they occasionally passed, it was sizeable at 50 feet. Aaron had told her it was an ex-charter yacht that he’d bought in New Zealand. It had the feel of a well-loved family home where each corner had a story to tell. She liked the rustic charm of the heavily varnished wood below deck that had turned an orangey colour over the years, and the quirks of how certain latches and doors had to be opened at a precise angle to make them work. He’d set up solar panels on deck, and a wind turbine too, and was eager that their travels left as little wake as possible.

‘Shell was telling me that your first voyage on The Blue was from New Zealand to Australia?’

He nodded slowly.

‘Some journey. Brave to do it single-handedly.’

‘Or foolish.’ He cut another slice of apple, crunching it between his teeth as he looked at the line of islands ahead, which were beginning to reveal craggy rock faces.

‘What made you decide to do it?’

‘Wanted a new experience, I guess.’

Lana thought about his answer: Aaron had bought a yacht, spent six months refitting it, then sailed off single-handedly. There must have been a compelling reason to make him take on such a challenge. Or, she thought, a compelling reason to make him want to leave New Zealand. ‘What did you do before this? Before setting sail?’

Aaron looked steadily ahead. He spoke slowly and clearly as he said, ‘I did a lot of things before this, Lana. But what I do now is sail.’ He cut a final slice of apple, then returned the knife to its sheaf before wandering away to the bow. He stood alone, one hand on the lifeline, his gaze on the water.

The wind continued to blow.

*

It was dusk by the time they’d finally finished anchoring in a spot Aaron was comfortable with. Once everything was done, he called the crew into the saloon, where they all squeezed around the main table.

Aaron remained standing, saying, ‘We need a quick group vote. We’re spending the night here – possibly tomorrow night, too. After that I wanted to find out where people would like to go next. We’ve got a couple of options.’ Flattening out a chart in the centre of the table, Aaron explained how they could tour the islands north-east of here where there were some great surf breaks, but that the sailing might be rough – or they could head south-east into more protected waters, where the snorkelling and diving were meant to be spectacular.

When he’d finished explaining the options, he asked for everyone’s vote, giving his own first. ‘I’m in favour of going north. It’d be good to see if there’s any swell running.’

Shell, who was sitting beside him, voted next. ‘Sorry, but I’m going to say south. I’d rather be snorkelling than wave-hunting.’

Heinrich voted in agreement with Shell, while Denny and Joseph voted with Aaron. Then it was just Lana and Kitty remaining.

‘North or south?’ Aaron asked them.

Lana felt oddly privileged to be included in the voting, as if it made them valued members of the crew. It was a fair and democratic system, and she respected Aaron for implementing it when, as skipper, he’d have been within his rights to make all the decisions himself.

‘Both routes sound amazing, but I’d love to do some more snorkelling, so I’m going to vote south,’ Lana said.

Kitty agreed – and so the decision was made.

‘You ever get the impression,’ Denny said to Aaron as everyone started getting to their feet, ‘that we’re not going to make the pro surf tour after all?’

‘Tough break,’ Aaron said, slapping a hand on Denny’s shoulder.

*

After the group vote, Lana and Kitty made dinner for the crew, stir-frying shellfish that Denny had gathered earlier in the day.

They served the food in plastic bowls and carried them up on deck, where a light breeze stirred the moonlit bay. Lana sat with her back against the lifeline, studying the curved shadow of the island ahead. The island, Topeu, shown on the charts as being less than 0.5 kilometres wide, was reputed to have fantastic rock formations and cliffs, which Lana was looking forward to exploring in the morning.

After dinner, Shell and Heinrich cleared the bowls, rinsing them in a large bucket of sea water and then taking them below deck to finish them off with fresh water. Aaron was fastidious about saving water; showers were a luxury that usually lasted three minutes, and washing up was done in an inch of water. They had a tank on board that was filled up whenever possible, but in the remote areas they sailed through, it wasn’t always easy to find somewhere to do so. Catching rainwater was helpful, but they had a desalinator installed as a backup, though the pump was noisy and drained a lot of energy and the small amounts of water it produced tasted flat.

Heinrich returned to the deck with a bottle of rum and a tray of glasses and, like most nights, the crew talked and drank and laughed as the yacht dozed at its anchor. Lana sat a little way apart from the others, her gaze cast at the sky, which was a deep velvet black, shot through with starlight. The warm breeze, scented with salt and earth, moved her hair against her shoulders, and she could hear crickets calling from somewhere on land.

There was a roar of laughter, and Lana looked around. Kitty was at the centre of the group recounting a story from the last play she’d been in. ‘That,’ she said, pausing theatrically, ‘was when I realized – he wasn’t wearing anything. Stark. Bollock. Naked!’

Shell clapped her hands together. Heinrich snorted.

Denny leant across the table and picked up the rum. He topped up the glasses of those nearest him, then stood and walked over to Lana with the bottle. ‘More?’

‘Thank you,’ she said, holding out her glass.

Once he’d refilled it, he sat down beside her, pressing his back against the guardrail.

Lana turned to him. ‘Does it ever wear off? The beauty of doing this?’

He took a drink and considered the question. ‘Maybe the freshness fades a little – you know, that excitement of the first time you anchor, the first night swim, the first time you’re out of sight of land. But, no, I don’t think the beauty wears off.’

She nodded, pleased with the answer. She tried to imagine being out of sight of land, wondering how many miles you’d need to sail before the coast slipped away completely.

Denny asked, ‘How long d’you think you and Kitty will stay on?’

The Blue was heading for its home port in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, which Aaron wanted to reach by November or December at the latest because of the cyclone season. The loose route they were aiming for was sailing east from the Philippines to Palau. Then they’d head south-east to Papua New Guinea, Fiji and finally New Zealand. Everything was dependent upon the weather, so nothing was fixed. Lana would love to stay for the entire journey, which would take around eight months, but realistically their money would only last another three months or so – and that’s if they were careful. ‘I suppose we’ll travel as far as we can afford.’

He nodded.

Up ahead at the bow, Lana noticed a flicker of light as Joseph lit a cigarette. Most evenings he sat alone, writing in a slim leather notebook that he kept tucked in his shirt pocket. She could relate to his need for some time to himself because, much as she loved being on the yacht, there was almost no privacy: you shared cabins, ate meals as a group, worked together, socialized together, and if you walked twenty paces you’d have crossed from one end of the boat to the other.

She asked Denny, ‘What’s Joseph’s story?’

‘We picked him up on this remote little island, five or six weeks back – it was Christmas Eve actually. There aren’t many tourists down that way and we’d moored at this cove out of town. On the beach was a tarpaulin draped between the trees – looked like a fisherman’s shelter or something. In it, we found Joseph sleeping rough. He was bone thin, didn’t look like he’d eaten properly in days. I invited him on the yacht for some food. Afterwards he asked if he could sail on with us. We voted – and here he is.’

‘What was he doing out there?’

‘The way he was living, we thought he was homeless. But he has money – inheritance, I think.’ He lifted his shoulders saying, ‘Maybe he just needed some space for a while, or wanted to get away from the tourist belt. Who knows?’

Lana watched the beam of Joseph’s head torch moving across a notebook he was writing in. ‘I suppose everyone’s got their story.’

Denny turned to her with a smile and said, ‘So tell me, Lana, what’s yours?’ ‘Mine?’

He nodded. ‘You spun a globe, picked a destination, ended up here. You put your life in the hands of chance. Why?’

An image of her father – shoulders rounded as he stood in the doorway of his room – flashed into her thoughts. She shook her head, pushing the memory away.

‘Why not?’ Lana said, immediately regretting the defensive edge to her voice.

He looked at her for a long moment, then said lightly, ‘I guess then I’ll just be thankful to the gods of Chance – because if it hadn’t been for that globe you spun, or for that kamikaze cockerel back in Norappi – we might never have met.’

She glanced at Denny. He was smiling at her and she felt warmth flood to her cheeks. He took a drink and, as he lowered his arm again, it rested against Lana’s. She became aware of the place where their bare skin met, and felt a low stirring in the base of her stomach.

There was a sudden splash in the water, followed by the sound of laughter. Lana peered over the side of the yacht to see Shell treading water, her blonde hair pasted to her head. ‘Who’s coming in?’

*

Lana slipped from her dress, tightened her bikini, and dived.

She loved that split second before she hit the water when she was falling forwards, completely committed, her hair blown back by the motion, her body straightening out as it plummeted downwards.

She cut through the surface and the sea wrapped around her, bubbled song filling her ears. She didn’t kick or move, just let herself fall deeper and deeper. There was a moment of pause and then the sea began to lift her up, raising her to the surface, to the air, to the night.

She could hear the voices of others already in the water. Only Kitty was still on deck. ‘Lana?’ she called from the bow, where she was pacing in her bikini. ‘What’s it like?’

‘Beautiful. I’ll swim around to the stern. Lower yourself in from there.’

Lana swam with smooth, easy strokes, enjoying the magic of being in the sea at night, feeling the water slip over her skin. Since joining the yacht, they had been in and out of the sea all day and she was finding that her muscles were beginning to tone. When she reached the stern, Kitty was standing there, arms wrapped around her middle. ‘I’ll count you in,’ Lana said.

‘Okay.’

‘One, two, three … three and a half … four—’

There was a splash and suddenly Kitty was in the water too, squealing and laughing and coughing. Kitty had always been a nervous swimmer and she paddled madly towards Lana, looping her arms around her neck whilst she caught her breath. ‘Do you think there’s seaweed and stuff below us?’ Kitty whispered, blinking salt water from her eyes.

‘No, it’s fine. Just clear water,’ she answered. ‘Happy to swim a bit further out?’

‘Not too far.’

They swam slowly, Kitty doing breaststroke with her chin raised above the waterline, Lana keeping level with her. When they were a short way from the yacht they stopped, treading water.

The Blue looked even more beautiful from here, the yacht lights casting a twinkling reflection in the water. There was barely a breeze tonight and they lolled on their backs, watching the stars and hearing birds call from hidden nooks within the island beyond them.

‘This is incredible,’ Kitty said, reaching out a hand and finding Lana’s. They drifted on their backs, hands held, hair swirling around their faces. There was the light sound of splashing as the rest of the crew swam towards them, their voices carrying across the water.

‘Did someone check the steps?’ Heinrich said.

‘Nope,’ Shell said.

‘Me neither,’ Denny added.

‘No,’ Joseph responded.

Aaron spoke then. ‘Are you serious? No one put them down?’

‘What?’ Kitty asked, treading water now. ‘What is it?’

‘You must’ve heard about that couple in the doldrums?’ Heinrich said.

Kitty shook her head. ‘What couple?’

‘They decided to go swimming off their yacht. It was still – like this – and they both dived in. They were messing around in the water, enjoying themselves, cooling off. After a while, they started to get tired, so they swam back to the yacht – only they realized that neither of them had thought to put down the ladder. They couldn’t get back on the boat.’

‘There must’ve been some way,’ Kitty said.

‘No ladder, no footholds, nothing to grab onto except the smooth shining surface of the hull.’

‘But they got back on eventually, though?’ Kitty asked.

In the darkness Aaron shook his head. ‘The empty yacht was found six weeks later – with their fingernail marks scarred into the hull.’

‘But … what … are the steps down now? Someone must’ve put them down.’ Kitty’s voice was cut with panic.

‘Kit,’ Lana said gently, ‘remember you jumped off the swim platform. It’s low enough to pull ourselves back on. They’re winding us up.’

Heinrich and Aaron laughed.

Kitty splashed them both. ‘Arseholes!’

‘Just trying to distract you from the sharks and sea snakes,’ Aaron said, deadpan.

She snorted. ‘I’m swimming back.’

The others joined Kitty, but Lana said she’d catch up, wanting a few moments alone. She floated on her back, letting the dark sea bear her weight. She felt a surge of freedom, a sense of possibility, a feeling that she and Kitty were part of something bold and wonderful that was so much more than the life they’d left in England. She wanted to seal this feeling in her heart. She closed her eyes, suspended in the sea, the voices of her friends slipping further away.

She became aware of a shift in the water, a new vibration in the liquid stillness. There was the brush of something against her skin, as if a hand was sliding down the length of her back and over the rise of her buttocks. She kicked out in surprise, waiting for whoever it was to surface laughing. After a while … thirty seconds, then a minute … there was no one.

She turned in the water, glancing about her, a trail of goosebumps spreading down her neck. It looked as though the rest of the crew had reached the stern and were pulling themselves out of the sea, although she couldn’t clearly make out if they were all there.

Had she imagined it? If one of the others had been fooling around, surely they would have grabbed her ankle or leg, pretending to be a shark – whereas this was insidious, just the breath of a touch, like a dark eel slithering against her skin.

Lana shivered. She swam hard towards the yacht, and scrambled up onto the stern, scraping her shin on the metal edge in her hurry.

Kitty had fetched a towel and, when she saw Lana, she wrapped it around them both so their cool bodies were pressed together.

‘Kit,’ she whispered, ‘did you see anyone just swim over to me?’

‘No. Why?’

‘Just now it felt like … like someone ran a hand along my back underwater.’

‘You sure?’ Kitty said, looking bemused.

Glancing about her, Lana could see all of the crew – Shell, Heinrich, Denny, Aaron and Joseph – drying off on deck. Had one of them managed to swim back here before her?

She looked out across the dark water. But the sea was eerily still, not a ripple in its surface.