Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

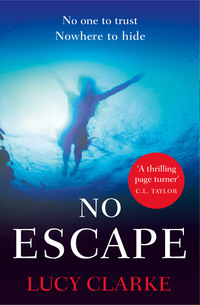

Kitabı oku: «No Escape», sayfa 5

7

NOW

The Maritime Rescue Centre is set at the edge of a commercial port, and Lana drives in behind a container lorry. She parks in front of a squat, flat-roofed building, but doesn’t get out immediately. Her wrists ache from where she’s been gripping the steering wheel too tightly.

She’s not sure what she’s doing here – what she expects to happen next. All she knew was that she couldn’t wait in the apartment any longer. So she scribbled a quick note of apology to her boss, which she left downstairs in the gallery, and then drove with the radio on hoping for a further update.

As she sits in the car now, she thinks there’s something soothing about a stationary vehicle, the wind locked out, the warm air trapped inside, and the feeling of being sealed off from the rest of the world. Being on the yacht was different; you felt the world and the elements in all their rawness – each gust of wind hitting your face, the roll and rise of swell surging beneath you, the heat of the sun searing across your skin. The sea demanded your constant attention.

Beside her on the passenger seat are a stack of old sketchbooks and three blunt pencils. Sometimes at weekends, Lana will get in the car and drive along the coast without a plan or a specific destination, simply pulling over whenever the desire to do so takes hold. Then she’ll climb into the passenger seat, prop a sketchbook on her knees, and draw for hours and hours.

It takes her back to the long afternoons in the school art room where she would sit with her elbow on the paint-stained desk, her hair falling down one side of her face, the sun slanting in through tall sash windows. The art room was a refuge from the rest of school life, which seemed drab and predictable. Apart from Kitty, Lana struggled to make friends. The other girls teased her for her quirky shoes, her thick amber hair, and the bright woollen tights she wore on home-clothes day. Her father had little money, so Lana’s wardrobe was comprised of odds and ends she’d pick up from charity shops on their monthly visit to town.

In the art room Lana felt comfortable. It was a place of colour and noise and warmth, where the radio played constantly in the background, and the air smelt of turpentine, coffee and the chalky scent of cheap paint. She sat next to Kitty on a high wooden stool, enjoying her constant chatter as Kitty made swirling patterns with a palette of pinks and purples.

Lana was fourteen when her art teacher, Mrs Dano, called her back after class. She’d spent the lesson scrawling a stub of charcoal across an A3 page and ignoring the still-life display of weighing scales she was meant to be drawing. She screwed up each piece of work, lobbing them all in the bin and, when the bell went, she’d slung her bag over her shoulder and started lumbering from the room.

‘Lana?’ Mrs Dano had called as she stood at the sink washing up paint-streaked jam jars. ‘A word, please.’

Lana had rolled her eyes at Kitty, then hung back, leaning a hip against the wall.

Once the room had emptied, Mrs Dano set aside the jam jars and wiped her hands on her apron, then went to the corner of the room, returning with three balls of screwed-up paper. She placed them on the desk in front of Lana. ‘Please would you open these?’

Lana’s jaw tightened as she picked up the first ball. The paper felt as crisp as dried leaves as she unscrewed the picture. It was a drawing of the windows of the art room, with an angry slash of charcoal across the centre that had torn the page.

Mrs Dano placed a finger in the left-hand corner, her amethyst ring catching in the sun. ‘Here,’ she said. ‘The light. You’ve got it just right as it cuts through the glass. And here, too,’ she said, sliding her finger lower. ‘Hmm, no, this bit isn’t quite right. The perspective is off, but if you just—’ Mrs Dano pulled a piece of charcoal from the pocket of her apron – ‘put the line this way,’ she said, dusting the charcoal across the page, ‘and applied a lighter pressure to shade it, you’d be there.’

With a change of stroke, the drawing had been transformed.

Mrs Dano rested her hands on the edge of the table. ‘I don’t want any more work going in the bin, Lana. There is beauty in imperfection. Remember that.’

Lana nodded. Then the wooden legs of her stool scraped across the floor as she stood.

‘And Lana?’

She turned.

‘If you ever want to use the art room in your lunch breaks, I’m usually in here.’ Mrs Dano held her gaze. ‘You’ve got talent. I’d like to see it grow.’

Lana had left the room, pleasure blooming hot in her cheeks. Outside the door, Kitty had been waiting, listening. She reached for Lana’s hand, their fingers threading together. ‘I knew it!’ she whispered. ‘I knew someone would notice your talent.’

*

Lana cannot delay going inside any longer. She takes a deep breath and opens the car door, stepping out onto concrete that shimmers with spilt diesel. The wind teases her dress around her thighs, making it seem as though the white sparrows of the pattern are fluttering and flying across the powder-green fabric.

The air is tinged with fumes and the scent of brine washing in from the water as she walks towards the main building. She comes to a reception desk that is unmanned and waits for a moment, peering into the back office – but the place is empty, computer screens off.

She moves beyond it, following a long corridor of rooms, all with their doors shut. She pauses outside a door that reads ‘Operations Room’ – then knocks.

The door is opened abruptly by a tall man with a thick black moustache, who introduces himself as Paul Carter, the man she spoke to on the phone. He wears hiking boots with brown socks pulled halfway up his calves. He strikes her as the sort of bloke who probably likes to spend his Friday evenings at one of the municipal beach-barbecue areas that are popular in New Zealand, although now his expression is strained, his brows heavy.

Behind him Lana can see a woman working in front of a computer screen. To her left is a noticeboard covered with maps, charts and printed weather reports. In the centre a sheet of white paper has been pinned, headed with the title, ‘The Blue: Crew List’.

Lana’s insides tighten. The names of the crew have been written in thick black marker pen and she scans each of them, her fists balled at her sides, palms sweating.

Each and every one of those five names dredges up memories that come flooding to the surface of her thoughts. Her heart pounds. It is only when Paul Carter takes a small step to the side, blocking her view of the noticeboard, that she looks up.

‘Can I help you?’ he asks coolly.

She swallows. ‘I’m Lana Lowe. I called earlier about The Blue.’

‘You shouldn’t be in here.’

‘There wasn’t anyone on reception,’ she tells him.

‘I’m afraid you need to leave—’

‘I know the yacht,’ Lana says desperately. ‘I used to sail on it.’

That catches his attention. ‘You did? When?’

‘Earlier this year – from January to March.’

‘Are you familiar with what safety equipment and communication devices they had on board? We’ve only had limited contact with them.’

She thinks for a moment, sweeping her mind over the yacht. ‘There were just the standard things – a life raft, life jackets, a grab bag, flares, an EPIRB. There was the VHF radio, and maybe another type, too.’ She can’t remember the names of things any more – the details of the yacht that were once so familiar are now beginning to slip away.

‘What about a satellite phone or personal locator beacons?’

‘No, not that I know of. None of those.’

Paul Carter nods, taking this in.

Lana asks, ‘What happened out there?’

‘I’m afraid I need to get back to my desk now.’

‘Please,’ she says. ‘My friends are on board.’

Paul Carter looks at her, then across at his female colleague. ‘All I can say at the moment is that the crew got into difficulties and had to abandon the vessel.’

‘Is there any news? Are the crew safe?’

‘Search and Rescue are doing everything they can, but no, there’s no news yet. A distress broadcast has been put out to all the vessels in the region, and a sailing yacht and merchant ship are diverting course to approach the search area.’

‘Approach? No one is even there yet?’

‘Both vessels were over forty miles away at the time. The Search and Rescue helicopter is already in the search area and we’re expecting more news soon.’

‘Did the crew make it onto the life raft?’

‘We have no information about that, I’m afraid.’

‘So … they could be in the water?’

‘It is possible, yes.’

*

Lana is desperate to remain in the Operations Room, knowing that Paul Carter will be the first person to receive any news, but he tells her, ‘One of my colleagues has organized a waiting room for relatives. Other family members are on their way here.’

Who, she thinks? The only crew with family in New Zealand are Aaron and Denny. She imagines Denny’s parents would want to be here; she remembers him talking about how much he missed them. It would be over two years since he saw them last.

‘I’ll take you there now.’ He looks over his shoulder. ‘Fiona, which room have they allocated?’

‘I think it was Twelve A,’ she says, hands poised above a keyboard.

Somewhere in the office a radio begins to beep. Paul Carter moves towards a desk where a large monitor is mounted. He picks up a hand-held device attached to it. A voice at the other end is saying, ‘Maritime Rescue, Maritime Rescue, this is Team One, this is Team One. Can you hear us?’

Paul Carter holds the radio handset to his mouth. ‘This is Maritime Rescue. Go ahead, Team One.’

‘We have been tracking the EPIRB for The Blue and have now located it.’

Lana holds herself still, hope rising in her chest. Denny once explained that an EPIRB is a device that is set off in any rescue situation. It is registered to a vessel and gives off the precise position via GPS, and then continues to transmit its position until the device – and hopefully crew – are located.

‘Go ahead, Team One. What is the current position?’

‘The position is 32*59.098′S, 173*16.662′E. I repeat, the position is 32*59.098′S, 173*16.662′E.’

Paul Carter leans over his desk, typing the coordinates into one of the three screens that are set up on the main desk. ‘Copy that. Do you have a visual? Is the EPIRB aboard the life raft?’

There is a delay, then the rush of static.

Lana looks at Paul Carter’s expression. His brow is furrowed and his mouth is fixed in a serious line. ‘I repeat, is the EPIRB aboard the life raft?’

The reply comes over the radio, filling the room. ‘There is no life raft in sight. The EPIRB is attached to a body.’

8

THEN

The Blue turned lazily on its anchor, a light breeze stirring the water. On deck Heinrich was fiddling with a radio that he’d taken apart, the innards laid out on a tea towel, and beside him, Shell was sitting forward writing a postcard to her parents.

Lana had her sketchbook balanced on her knees, and was leaning close to the page, the tip of her tongue pressing against her front teeth. She moved the pencil in short, quick strokes, sketching a coil of rope that lay on deck in front of her. Looking at the page, she could see that the detailing at the end of the rope – where it trailed out of the coil and across the deck – wasn’t quite right. She tore the edge from the rubber she held and rolled it into a sharp point so she could erase with precision.

She spent a few minutes re-drawing until she was satisfied with it. Then she lifted the sketchbook from her knee and held it at arm’s length. Closing one eye, she studied it. The detailing in the curve of the rope was pleasing. She liked that the image spoke to her of order, things coiled tight, yet she’d also captured the weave of the rope where the threads had come loose – giving the suggestion of it starting to unravel.

Lana closed the sketchbook, setting her pencil on top. When she looked up, Joseph was storming down the deck, his face set in a heavy frown, his lips pinched. He came to a stop in front of Heinrich, casting him into shade.

‘Hello, room-mate,’ Heinrich said with a false smile. It was no secret that the two of them disliked sharing a cabin; often one of them ended up sleeping in the hammock on deck to have their own space.

‘Have you been through my backpack?’ Joseph demanded.

‘Your backpack?’

‘It is not how I left things! Someone has been through it!’ His fingers clenched and unclenched around his loose shirt sleeves.

‘Why would anyone want to do that?’ Heinrich asked leadingly.

‘Have you?’

Heinrich rolled his eyes. ‘You really think I want to read those special stories you’re always busy writing?’

‘Heinrich!’ Shell chastised.

‘Course I haven’t been through your things,’ Heinrich said in a more conciliatory manner.

Joseph drew air deep into his lungs, steadying his breathing. After a moment he conceded, ‘It must be my mistake,’ although Lana noticed that his gaze lingered on Heinrich.

Eventually he turned away, took a tin of tobacco from his pocket, and swiftly made a roll-up. With his back to the others he lit it and inhaled, the tension in his shoulders beginning to soften.

In an attempt to lighten the atmosphere, Lana asked Shell, ‘How’s the postcard writing going?’ Any time they were in a town, Shell would scour the market stalls in search of postcards to send home to her parents.

‘Sometimes I feel like I’m writing a tourist brochure rather than sharing anything about how it actually feels to be here, you know?’

Lana nodded – although the truth was, she hadn’t been in touch with her father since coming away. Kitty had sent a couple of emails home, and Lana imagined that the news would gradually filter through to her father. ‘Your parents must love getting them.’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ Shell said, lifting her shoulders. ‘I never hear back from them. Not a single email. I don’t even know if they read my letters.’

Lana was taken aback. ‘Why wouldn’t they?’

‘We weren’t on the best terms when I left. They didn’t like my … life choices.’ She laughed as she said, ‘When I told them I was a lesbian, it was like there’d been a death. They grieved – actually grieved over the news.’

Joseph exhaled a drift of smoke into the clear blue sky. ‘Why do you still write?’

Shell turned and looked at him. ‘Because I want to at least try. They’re my family.’

‘Parents are not God. They are people. People who can be … fucking assholes, no?’ His voice was breathless with a sudden anger. ‘If they do not like who you are, then, so what? Yes?’

Shell’s eyes widened.

‘This – this is a waste!’ Joseph said, gesturing to the postcards with the roll-up.

‘Joseph …’ Heinrich said, and Lana caught the warning in his tone.

‘It is true, Shell. I just tell you truth. You are very nice, very kind girl. You waste your time thinking of them, if they do not think of you!’

Shell’s eyes turned glassy. Slowly, she gathered up her postcards and left the deck without a word.

Heinrich got to his feet too, glaring at Joseph. ‘Why the fuck did you say that?’

‘I only say what I think.’

‘Next time, don’t! Shell’s had a hard time of it, okay?’

Joseph drew on his roll-up. ‘Better to hear the truth, than live in dream, no?’

‘You,’ Heinrich said, pointing, ‘can be a little prick.’ He disappeared below deck after Shell, leaving the pieces of the dismantled radio gleaming silver in the sunlight.

Looking at Joseph, Lana could feel the bitterness and hurt locked away with his grief. She wondered what had happened between him and his parents.

He brought the roll-up to his lips, but before he inhaled he said, ‘I do not mean to make Shell cry. I like her very much. But I also believe when parents tell us, “We do this for you, because we love you,” they are not always right, are they?’

Lana contemplated this, thinking of her own father. ‘No,’ she said eventually. ‘They’re not.’

*

Lana returned to the cabin, where Kitty was lying in her bunk recovering from a hangover. She hadn’t made it up onto deck before mid-morning all week.

‘He didn’t mean to upset her – it’s just his manner,’ Lana was saying, filling Kitty in about Joseph. She knew he sometimes acted in odd ways, but she also knew he wasn’t cruel. ‘But I don’t think Heinrich saw it that way.’

‘When it comes to Shell, Heinrich does have a tendency to be a little overprotective,’ Kitty said, raising an eyebrow meaningfully.

‘You’ve noticed, too?’

‘Noticed?’ Kitty said. ‘He follows her around with his tongue hanging so far out that I’ve almost skidded over in his drool.’

‘Shhh!’ Lana said, laughing.

‘Trust him to fall for a lesbian. The ultimate challenge!’ Kitty said, taking off his accent perfectly.

Lana laughed again.

‘Hey, you know what Heinrich told me last night?’ Kitty lowered her voice and said, ‘Aaron used to be a barrister.’

‘Aaron? Seriously? How does Heinrich know that?’

‘When they were moored up somewhere in Thailand, this huge motorboat – a gin-palace type, owned by a Swiss guy – reversed right into The Blue. Put a hole in the stern. Then motored off.’

‘Aaron must’ve lost it!’

‘Apparently not. He caught up with the boat a day or two later. Heinrich reckoned he was lethally cool when he confronted the owner, didn’t raise his voice, didn’t get angry. Just told this bloke that, unless he sorted out the repair bill, Aaron would be going to the police, and started spouting all this legal speak about operating a motorboat under the influence, endangering lives, leaving the scene of a crime. Afterwards, Heinrich asked how he knew all that stuff and Aaron told him he used to be a barrister.’

Lana pictured him in a courtroom, chest puffed out, arguing his case – and found that the image came to mind easily. If he’d been a barrister, it probably explained how he could afford to buy The Blue in the first place. ‘Wonder why he gave it up.’

‘No idea.’

There must have been some reason. Barrister to skipper was some career swerve. She mused on this as she picked up her sketchbook and slipped it under the mattress of her bunk to keep it flat.

‘What’ve you been drawing?’ Kitty asked.

‘Just a coil of rope up on deck.’

‘Let’s have a look.’

Kitty was one of the only people Lana was happy to show her sketches to. The tutorials during her art degree had left behind a residue of fear – all those panic-inducing moments of standing in front of her peers, trying to put into words what she’d been hoping to capture in a piece. Even now she’d break out into a sweat when she had to speak to a roomful of people. Lana slid out the sketchbook and opened it at the image of the rope.

Kitty studied it carefully. ‘Lana,’ she said, looking up. ‘This is beautiful.’

‘It’s just a rope.’

‘But look at the detail! It’s amazing. It’s how you’ve captured it.’ She shook her head thoughtfully. ‘I can’t wait to see your work hanging in a gallery one day.’

Lana laughed. ‘You’ve got a high opinion of me.’

‘Yes,’ she said seriously. ‘I have.’

Lana was reminded how – even when they were teenagers – Kitty had always encouraged Lana’s passion for art. ‘Do you remember how we used to make that tepee den in my back garden and hide out in it over summer?’ she said, thinking about how she’d draw in the shade, while Kitty filled the space with her chatter and the smell of drying nail polish.

Kitty said, ‘We’d tie a piece of string between the shed and rotary dryer and drape a sheet over it, pegging the corners out wide. Then we’d bring out all the blankets and cushions we could find, and camp out there for hours.’

Hidden within the folds of the sheets they’d talk as if they were invisible to the rest of the world. ‘We’d spend hours and hours imagining what our mothers would be like if they were still here, the things that we’d do together.’

‘Think we decided they’d be best friends so they could take us on holidays together,’ Kitty said with a smile.

Lana nodded, but she couldn’t match Kitty’s smile. ‘All that time I was imagining her – fantasizing about what a perfect mother she’d have been, thinking about how deeply she must have loved me – she was alive. She was living a new life in another country.’

‘Oh, Lana,’ Kitty said softly.

‘I just … I still can’t get my head around it,’ she said, the familiar anger rising inside her. It was always there, hovering just beneath the surface. ‘Aren’t mothers supposed to love their children unconditionally? Yet she … she just left. Fucked off. All those tears I cried for her over the years – imagining the car crash, wondering whether the medical team had arrived quickly enough, picturing the driver who caused the crash. But there was no driver, no accident, no medics – just a woman who didn’t love her family enough to stay.’

‘That’s not true,’ Kitty said.

‘Isn’t it? And him,’ she said bitterly. ‘He lied about it all. If I’d known the truth I could have at least tried to get in touch with her – had the chance to ask why she left. But he robbed me of that. And now it’s too late. I don’t think I can ever forgive him for that.’

‘You mustn’t say that. He was trying to protect you. He did what he thought was right.’

Lana rolled her eyes. ‘Kit, sometimes you sound like him.’

‘I just … I don’t want you to lose him. He’s your only family.’

Lana shook her head. ‘No, you’re my family. You always have been.’

Kitty put her arms around Lana. She smelt of rum and stale cigarettes.

‘What a fuck-up,’ Lana said, her mouth against Kitty’s hair. ‘I drag you halfway around the world to get away from my father, and here I am – on a yacht in the middle of the Philippines – still talking about him.’

‘Dragged me?’ Kitty said. ‘You just try leaving me behind.’

*

When Lana climbed up on deck later, Denny was returning from a swim. He pulled himself onto the stern, water pouring off him. ‘I’ve got something to show you.’

‘Oh?’ Lana said.

‘It’s on the island. Wanna swim over there?’

Lana looked across to the island. It was probably about a ten-minute swim, easily manageable when there was little wind. ‘Sure,’ she agreed, thinking she could use the exercise to clear her head.

Since their night swim together, Lana had found herself waking early and joining Denny in the saloon, where he’d be working. He’d close his laptop, make a fresh pot of coffee, and the two of them would sit up on deck talking as dawn broke. Those early mornings – before the rest of the crew rose – were becoming her favourite part of the day.

Together, they swam to the island. It took longer than Lana had thought but Denny stayed at her side, never overtaking her, and they covered the distance easily.

On the shoreline she rubbed the salt water from her eyes and wrung out her hair, then followed Denny along the beach, water dripping from the ties of her bikini. They kept close to the treeline where the sand was cool enough to walk on. ‘Where are we going?’

He didn’t answer, so she continued following him until they came to a halt by some rocks. ‘Here,’ he said, pointing towards a craggy gap, no larger than a cupboard door.

‘A cave?’

He scrambled over a boulder, then carefully lowered himself into the dark space between the rocks.

‘What can you see?’ she called as Denny disappeared from sight.

There was no answer.

‘Denny?’

She clambered onto the boulder and slipped her legs through the gap as he had done, feeling the scuff of rock against the backs of her thighs. She waited, gripped there until her eyes adjusted.

Below she could see the ground only a few feet away. She jumped, landing with a thud. ‘Denny?’

His name came back to her, reverberating off the cave walls. She crept slowly forward. ‘Where are you?’

‘Over here,’ he whispered. ‘Come and see this, Lana.’

She moved slowly, her lungs filling with the cool, dank air.

Gradually her vision began to adjust so she could make out the shapes of the cave. There was a brighter patch of light further ahead where daylight was spilling in.

Denny was standing on top of a wide boulder in a stream of light. He turned towards her and held out his hand, helping her up onto the boulder. Standing beside him, she gasped.

Jagged arrows of limestone rose from the ground, stretching hundreds of feet upward. They reached towards the sky like cold fingers, wanting to touch the sun. Daylight beamed in through the gaps, illuminating the incredible dusky grey and earthy shades of the pinnacles, making her feel as if they’d wandered into an ancient cathedral. All she could hear was the faint drip of water from the rocks, the beat of her heart in her chest, and the shallow draw of her breath.

Her thoughts slipped to the warmth of Denny’s grip and the heat of his body at her side.

Out of the sun and in the damp half-light of the limestone cave, Lana shivered.

Denny drew Lana in front of him and wrapped his arms around her, resting his chin lightly on her bare shoulder. It was the beautifully easy motion of old lovers, their bodies settling against one another as if moulded together over time.

Lana’s gaze wandered over the hidden grandeur of the cave, absorbing the natural arches and sculpted grooves. ‘It’s beautiful,’ she whispered.

‘Yes,’ he said, his lips at her ear.

She felt her heart rate increasing as desire pulsed through her, sure and absolute. She turned within the space of his arms and felt the brush of his shoulder against hers. She raised her eyes to his.

The pale blue of his irises deepened as she looked into them. She became aware of the cool air at her back, and the warmth of Denny in front of her.

‘You know that we shouldn’t …’ he said, but there was little conviction in his voice.

She thought of Aaron’s rule: No relationships between the crew. But those words diffused like smoke as she lifted her face, placing her mouth against his.

There was a moment – before their lips began to move together – when time seemed suspended. Their eyes were open, fixed on each other, lips touching; it was like standing on the edge of a cliff the second before diving in – the heady anticipation, the inevitability of what was coming next. Then their lips pressed deeply together, Lana’s tongue sliding into the warmth of Denny’s mouth. A low sound of desire came from his throat. She felt his fingers at the base of her neck, running through her hair, tilting her head back as he kissed her more deeply.

Something tight inside Lana began to loosen and melt away. His skin was hot against hers and the heat seemed to spread through her.

Later, a lifetime later, they pulled apart and Denny rested his forehead against hers, his hands still holding her close. She could hear the raised tempo of his breathing.

‘Wow, Lana Lowe,’ was all he whispered.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.