Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

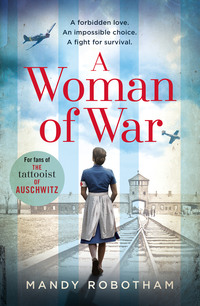

Kitabı oku: «A Woman of War», sayfa 2

2

Exit

Just the words caused me to shake visibly: ‘The Commandant wants to see you.’ Eyes widened amid the gloom of the hut, and all movement stopped. There was no sound, just a stale breath of fear rising above the stench of humans as animals: urine and excrement, feminine issue, and the shadow smell of birth. My hands were wet with pus, and the trooper looked at them with obvious disgust. I scouted for a cloth not yet sodden, and it took me a moment in the darkness.

‘Hurry!’ he said. ‘Don’t keep him waiting.’

At that point, my thoughts were clear: I am going to die anyway, I might as well not hasten the event. No one was called before the Commandment for a friendly afternoon chat.

Ironically, it was the icy wind whipping through the holes in my dress that stopped me shaking, my body’s remaining muscles tensing to keep in whatever warmth it could. Across the barren yard, more eyes settled on me, their gazes sketching my fate, as I struggled to keep up with the goose-step pace of the trooper. ‘Oh, we remember Anke,’ they would later say, in the dank of their own huts. ‘I remember the day she was called to the Commandant. We never saw her again.’ If lucky, I might be one of many such memories, a story to be told.

The guard led me through the scrub of the sheds, and then up to the gate to the main house, shooing me inside with a gruff: ‘Go, go!’ I had never seen the door to the house, and slowed to marvel at the intricate carvings on the outside, of angels and nymphs, no doubt the work of Ira, the woodcarver and stonemason, who’d died of pneumonia the previous winter. His pride in his work showed through, even at the gates of the enemy, although I glimpsed a tiny gargoyle sandwiched between two roses, a clear image of Nazi evil. His little slice of sedition gave me a hint of courage as I clumped up the steps towards the door.

Inside, my cheeks burned with the sudden heat and my top lip sprouted small beads of moisture, which I licked off, enjoying the tincture of salt. In the wide, wooden-clad hallway, a fire roared in a grate, fuel stacked beside it that would have saved a dozen of the babies I had seen perish over these last months. I was neither surprised nor shocked, and I hated myself for the lack of emotion. We’d become used to rationing feelings to those that could accomplish something; rage was wasted energy, but irritation bred cunning and compromise, and saved lives.

The trooper eyed my skeletal limbs, barking at me to wait by the fire, which I took as a small token of humanity. I stood outwards, letting it burn my bony rump through the threadbare dress, feeling it quickly sear my skin and almost enjoying the near pain. The trooper rapped noisily on a dark wooden door, there was a voice from inside and I was beckoned from the fireside to walk through.

He had his back to me, hair almost white blond – an Aryan poster boy. The trooper clicked his heels like a Spanish dancer, and the head swivelled in his chair, revealing the model man Nazi; sharp cheekbones, taut and healthy, a rich diet colouring his flesh pink, like the tinted flamingos I remembered seeing at Berlin’s zoo with my father. Skin tones in the rest of the camp were variations on grey.

He shuffled some papers and set his eyes on my feet. A sudden, hot shame washed over me at the obvious holes in my boots, then a swift anger at myself for even entertaining such guilt – he and his kind had engineered those holes, and the painful welts on my leathery soles. His gaze flicked upwards, ignoring the wreckage between feet and head.

‘Fräulein Hoff,’ he began. ‘You are well?’

We might as well have been at a tea party, the way he said it, a passing comment to a maiden aunt or a pretty girl. Irritation rose again, and I couldn’t bring myself to answer. Absently, he’d already gone back to his papers, and it was only the silence that caused him to look up again.

I thought: I have nothing to lose. ‘You can see how well I am,’ I said flatly.

Strangely, there was no rage at my dissidence, and I realised then he had a task to carry out, a distasteful but necessary chore.

‘Hmm,’ he said. ‘You act as a camp midwife? Helping the women, all the women?’

He looked at me with deep disdain, at my dark looks, which naturally straddled the German and Jewish worlds.

‘I do,’ I said, with a note of pride.

‘And you worked in the Berlin hospitals before the war? As a midwife?’

‘I did.’

‘Your reputation is a good one, by all accounts,’ he said, reading from sheets in front of him. ‘You were in charge of the labour ward, and rose to the rank of Sister.’

‘I did.’ I was beginning to be slightly bored by his lack of emotion; even anger was absent.

‘And my staff here tell me you have never lost a baby in your care during your time here?’

‘Not at birth,’ I said, this time with defiance. ‘Before and after is common.’

‘Yes, well …’ He skated over death as if waving away the offer of more tea or wine. ‘And your family?’

This was where my pride and bloody-mindedness deserted me, falling to the level of my holey boots. A well of hurt caught deep in my throat and I swallowed it like hot coals.

‘I have a mother, father, sister and brother, possibly in the camps,’ I managed. ‘They may be dead.’

‘Well, I have some news of them,’ he said, accent shorn and clipped. ‘You come from a good German family by all accounts – but your father, he is not a supporter of the war, as you know, and your brother neither. They are, of course, in our care, and alive. They know of your status too.’ His eyes tacked briefly upwards to assess my reaction. When there was none, he turned back.

‘You should know this because of the proposal I am about to put to you.’ His tone suggested he was offering me a bank loan, rather than my life. At that moment, I pondered on whether he hugged his mother when they met, kissed her with meaning, had sobbed on her like a baby. Or had he been born a callous bastard? I speculated whether war had made him like this, a vacuum in uniform. I was amusing myself nicely, my bones finally warming from his own fiery grate. I might die feeling warmth, and not with blue, icy blood limping through my veins. I would bleed well all over his nice, scrubbed floor, and cause him some grief, more than mere inconvenience. I hoped his boots would slip and slide on my ruby issue, a stain sinking into the leather, forever present.

‘Fräulein?’ It wasn’t the urgency in his voice that roused me, but a single gunshot out in the yard, a crack slicing through the quiet of his office. One of several heard every day. He didn’t flinch. ‘Fräulein, did you hear me?’

‘Yes.’

‘You have been summoned, by the highest authority – the Fuhrer’s office, no less.’ I expected a little trumpet fanfare to follow, the statement coated with such a gilded edge. ‘They have need of your services.’

I said nothing, unsure how to react.

‘You will leave in one hour,’ he said, as a sign of dismissal.

‘And if I don’t want to go?’ It was out of my mouth before I realised, as if something other than me had formed the words.

Now he was visibly annoyed, probably at his inability to shoot me, there and then in cold blood. As he had done many times before, so his reputation told us. The mere mention of the Fuhrer’s office signalled I wouldn’t die here, not today, if I agreed to go. The Commandant’s jaw set, the cheekbones rigid like a rock face, eyes a steel grey.

‘Then I can’t guarantee your family’s safety or outcome in the present troubles.’

So that was it. I would attend Nazi women and help give life, in exchange for avoiding a final death for my own family. There was nothing veiled in his meaning – we all knew where we stood.

‘And the women here?’ I said, ignoring his dismissal. ‘Who will see to them?’

‘They will manage,’ he said into his papers. ‘One hour, Fräulein. I advise you to be ready.’

My body was immune to the wind chill again as I was marched back to Hut 23. Strangely, I felt nothing physical, not even the reprieve of emerging from the main house alive. My mind, instead, was churning – of the things I needed to pass on to Rosa, just eighteen, but to date my most competent helper. Rosa had been with me at almost every camp birth in the past nine months, soothing when needed, holding hands, cleaning debris and mopping tears when the babies were plucked from their mothers, as they so often were.

No Jewish baby made it past twenty-four hours of birth at their mother’s side. The non-Jews were sometimes permitted to nurse their babes until the inevitable malnutrition or hypothermia took hold, but at least their mothers had closure. The Jewesses clutched only an empty void, their rhythmic sobs joining the whistling wind as it ripped through the sheds. Only one Jewish mother and baby had been ghosted out of the camp overnight, on the orders of a high-ranking officer, we suspected. We were divided on whether her fate was good or bad.

In the hut, the women greeted me with relief, then sorrow at my leaving. I had no belongings to pack, so that precious hour was spent in a breathless rundown with Rosa of the checks needing to be made, where our meagre stash of supplies was hidden. In sixty all too brief minutes, I did my best to pass on the experience I had learnt over nine years as a midwife: when shoulders were stuck, compresses on vaginal tears, if a bottom came first instead of the head, action to stop a woman bleeding out, sticky placentas. I couldn’t think or talk fast enough to include it all. Luckily Rosa was a fast learner. The normal cases she had seen many a time, and we’d had few abnormal ones too. I took her face in my hands, parched skin stretched around her large, brown eyes.

‘When you make it out of here, then you must promise me one thing,’ I told her. ‘Do your training, be a midwife, at least witness the good side of mothers and babies together. You’re a natural, Rosa. Make it through, and make a life for yourself.’

She nodded silently. Her pupils were sprouting tears now, genuine I knew, because none of us wasted precious fluid unless it drew hard on our hearts. It was the best farewell she could have given me.

A hammering on the shoddy door signalled the hour was up, and I had no time to return to my own hut. It would be empty anyway, Graunia and Kirsten – my human lifelines – on work detail. With no time allowed to seek them out, Rosa was charged with passing on my love and goodbyes. I hugged several on my way out, eyes down to disguise my own distress. I was getting out, but to what? A fate potentially worse than the ugliness of the camp. I couldn’t begin to contemplate what depth of my soul I might be expected to plunder.

A large black car was waiting, the type only Nazi officials travelled in, with a driver and a young sergeant to accompany me. The sergeant sat poker-faced, in the opposite corner on the back seat, his distaste at my physical and moral stench apparent, as a German with no allegiance to the Fatherland. Reluctantly, he pushed a blanket towards me. I hunkered into the soft leather, warmed by the luxury of real wool against my skin and the rolling engine, closing my eyes and falling into a deep – though uneasy – sleep.

Berlin, August 1939

They called us in one by one, plucked from our duties on the labour ward, into Matron’s office. She stood, impassive, while a man in a black suit sat behind her desk, looking very comfortable. By my turn, he must have read out the same directive enough times to know it by heart, and he barely looked at the paper in front of him.

‘Sister Hoff,’ he began, in a monotone, ‘you know how much the Reich values and appreciates your profession as gatekeepers of our future population.’

I looked solidly ahead.

‘Which is why we are so reliant on you and your colleagues to help us in maintaining the goal that we have, the goal of purity for the German nation.’

I’d been forced to sit through enough lectures on racial purity to know exactly what he meant, however much the language shrouded the obvious. The Nuremberg Laws had made marriage illegal between Jews and Aryans for several years and we’d seen a real decline in ‘mixed’ newborns in the hospital. Now that Jews were excluded from the welfare system, we barely came into contact with Jewish mothers any more, unless they were both rich and brave.

He went on. ‘Sister, I am here to share news of a new directive that will now become part of your existing role, effective immediately. We require that you report to us – via your superiors – all children either born, or that you come into contact with, where disability of any nature is suspected.’ Here he looked down at his list.

‘These conditions include: idiocy, mongolism, hydrocephaly, microcephaly, limb malformation—’ he took a bored breath ‘—paralysis and spastic condition, blindness and deafness. This list is, of course, not exhaustive, but acts as a guide only. We rely on your knowledge and discretion.’

Speech over, he looked at me directly. I continued staring somewhere between his temple and his oiled hairline while his eyes crawled over my face. I hoped beyond anything he wouldn’t ask me for a decision.

‘Do you understand that this is a directive, and not a request, Sister?’ he said.

‘I do.’ In that, I could be honest.

‘Then I am relying on your professionalism in working towards a Greater Germany. The Fuhrer himself recognises your vital role in this task, and ensures your … protection in law.’ He weighted the last words purposefully, and then continued lightly. ‘However, we do understand it is a drain on your time and knowledge, and there will be an appreciation payment of two Reich marks for every case reported, payable by the hospital.’ He smiled dutifully, at the generosity of such an offer, and to signal we were finished.

I wanted to howl inside, to take my too-short nails and gouge them deep into his tiny eyes set in too much flesh, made pinker and fatter by numerous trips to the bierkeller – sitting alongside his Nazi cronies, quaffing beer and laughing about ‘filthy scum Jews’. I wanted to hurt him, for presuming we were all as dirty and disgusting – as inhuman – as he had become. But I said and did nothing, just like Papa had told me. ‘Anke, there is diversity in defiance,’ my wise father advised. ‘Be clever in your deceit.’

The Nazi shuffled his papers and I saw Matron’s skirts shift from the corner of my eye. I knew her thoughts. ‘Keep calm, Anke, and, above all, keep quiet,’ she would be willing me.

‘Thank you, Sister Hoff,’ she said smartly, and piloted me swiftly out.

I went back to the ward – in my short absence, a woman’s fourth labour had progressed rapidly, and within the hour she was cradling her newest child, counting her fingers and toes and completely unaware that the efficient Reich would readily sacrifice her beautiful daughter if one such finger or toe were out of place. There was no mention of what would happen after we – as dutiful citizens – reported any disability, but it wasn’t a great stretch of the mind to foresee. I had no doubt it was not to build and provide excellent care facilities for such ‘unfortunates’. But in guessing their fate? I really didn’t want to delve too far into my own imagination. The increasing numbers of Hitler’s Brownshirts on the streets, and their open violence towards Jews, told us the boundaries were already breached. It was simple enough: to the Reich, there were no limits. No one – man, woman or child – was safe.

Every midwife, nurse and doctor had been spoken to, creating a strange conspiracy of silence. People were polite to each other – too polite – as if we already weeding out the dissidents, the non-committals among us. The labour ward was steady, but each birth brought a new question. Where once it was: ‘Boy or girl? How much do they weigh?’ now it was: ‘Everything all right?’ We were playing Russian roulette with an unknown number of chambers in the barrel – and no one wanted to be the first.

I thought back to a birth I’d attended a few years before, at the home of a Slovakian couple. The labour had been unusually long for a second baby, and the pushing stage exhausting. As I watched the baby’s head come through, the reason became obvious – a larger than average crown, which pulled on every ounce of the woman’s anatomy and spirit to birth. With the baby girl finally in her mother’s arms, we all saw why: a disproportionately swollen head, with eyes bulging from a heavy-set brow, one eye ghostly and opaque, unseeing, the other eye turned inwards, likely blind as well. The body was scrawny by comparison, as if the head had swallowed all the energy the mother had poured into the pregnancy. And all she said was: ‘Isn’t she lovely?’ The grandmother, too, cooing over the new life, content with what God had given them.

Beauty was never fixed so firmly in the eye of the beholder, as in that birth. I could only guess the mother might have shed private tears about the lost future of her beautiful daughter, or speculate about how long the baby survived. But I was even more certain that all babies are precious to someone, that we did not have the right to play judge, jury or God. Ever. I resolved firmly I would not be complicit. In the event it happened, I would find a way – I just didn’t know how.

Just one month later, Germany was at war with Europe, and the fabric of a whole nation was swiftly put to the test.

3

The Outside

A distinct chill in the air woke me. It was dark, and we were still travelling – the big engine purring steadily, a few lights sprinkled along the way, houses only just lit. I was disorientated, having no idea which direction we had come in, but I guessed we were in the mountains and climbing gently. The air felt different – a crystal edge, a taste recalled from family holidays.

I was surprised. I had assumed we would be in Berlin, Munich, or some other industrial town, headed for a private maternity home, where the wives of Nazi officials and loyal businessmen would be doing their duty – the women of Germany having been charged with procreating the next generation as their ‘military service’. Before I’d been evicted, posters had projected from every street corner in Berlin, recruiting to the ranks – blonde, smiling women with caring arms splayed around their strong, Aryan brood, ready to serve the Reich as rich fodder for the ranks. It was their duty, and they didn’t question it. Or did they? You would never know, since loyal German women didn’t speak out.

The sergeant startled as I moved, squaring his shoulders automatically. He spoke into the air. ‘We will be arriving soon, Fräulein. You should be ready.’

I was sitting in my only rags and had nothing to gather, but I nodded all the same. In minutes, we swept left through wrought-iron gates, rolling steadily up a long drive, icy gravel crunching underneath. At the top was a large chalet house, the porch lit by a glow from inside. The style was distinctly German, though in no way rustic, with carved columns supporting the large wraparound veranda, wooden chairs and small tables arranged to take advantage of the mountain view.

For a brief moment I thought we had arrived at a Lebensborn, Heinrich Himmler’s thinly veiled breeding centres for his utopian racial dream, and that my task was to safeguard the lives of Aryan babies, from appointed carrier women or the wives of SS officers. But this looked like someone’s home, albeit large and grand. I mused on what type of Nazi spouse would live here, how important she was to have caught the attention of the Fuhrer’s office and the promise of a private midwife.

The imposing wooden door opened as we drew to a stop, and a woman appeared. She was neither pregnant, nor the lady of the house, since she was dressed like a maid in a colourful bodice and dirndl. I stumbled slightly on getting out, legs numbed from the extreme comfort. The maid came down the steps, smiled broadly, and put out her hand. Her white breath hit the chill air, but her welcome was warm. This day was becoming ever more bizarre.

‘Welcome Fräulein,’ she said, in a thick Bavarian tone. ‘Please come in.’

She led me into an opulent hallway, ornate lamps highlighting the gilded pictures, Hitler in pride of place above the glowing fireplace; I had seen more welcoming fires today than in all my time in camp. I followed puppy-like through a door off the hallway, and we descended into what was clearly the servants’ quarters. Several heads turned as I came into a roomy parlour, eyes dressing me down as the maid led me through a corridor and finally to a small bedroom.

‘There,’ she said. ‘You’ll sleep here tonight before you see the mistress in the morning.’

I was struck dumb, a child faced with a magical birthday cake. The bed had a real mattress and bedspread, with a folded fresh nightdress on the plump pillow. A hairbrush sat on top of a sideboard, alongside a bar of soap and a clean towel. It was the stuff of dreams.

The maid prompted me again. ‘The mistress said to give you—’ she stopped, correcting herself ‘—to offer you a bath before you have some supper. Would that suit Fräulein?’

Quite how they had explained away my dishevelment was a mystery – my dark hair had grown back and my teeth were intact but I looked far from healthy. This maid was either ignorant of my origins, or at least disguised it well.

‘Yes, yes,’ I managed. ‘Thank you.’

She disappeared down the corridor, and the sound of running water hit my ears. Hot water! From taps! In the camp it had been scarce, cold and pumped from a dirty well. I couldn’t take my eyes off the tablet of soap, as if it were manna from heaven and I might bite into it at any moment, like Alice in her Wonderland.

I sat gingerly on the bed, feeling my bones sink into the soft material, never imagining that I would spend a night again under clean sheets. The maid – she said her name was Christa – led me to the bathroom, shutting the door and allowing me the first true solitude in two years. Despite the sounds of the house around, it was an eerie silence, the space around me edging in, claustrophobic. There was no one coughing into my own air, sucking on my own breath, no Graunia shifting her bones into the crevice of my missing flesh. I was alone. I wasn’t sure if I liked it.

I peeled off my thin dress, my underclothes almost disintegrating as they dropped to the floor. Steam curled in rings above the water, and I dipped in a toe, almost afraid to enter the water, in case a real sensation would pop this intricate dream.

Sinking under the delicious warmth, I wasted precious salt tears, when there was already water aplenty. When you saw so much horror, destruction and inhumanity in one place, it was the simplest things that broke your resolve and reminded you of kindness in the world. A warm bath was part of my childhood, but especially when I was thick with a cold, or racked with a cough. Mama would run the bath for me, sit talking and singing while she washed my hair, wrapping me in a soft towel before putting me to bed with a hot, soothing drink. I tried so hard not to think of them all, as I wallowed in the strangeness, but I hoped beyond everything they weren’t in the hell I’d just left behind. Heavy sobs shook my wasted muscles, until I was dry inside.

Tears exhausted, I surveyed my body for the first time in an age; there were no mirrors in the camp, and the cold meant we barely undressed. The very sight shook me. I counted my ribs under parchment flesh and saw that the arm muscles developed through hospital work were now flaccid and wasted, my hipbones projecting through my skin. Where I had disappeared to? Where had the old Anke gone? It took a good scrub with that glorious bar of soap to cut through the layers of grime, and the water was grey as I stepped out, tiny black corpses of varying insects lying on the leftover scum. Christa had laid out a light dressing gown for me, and I purposely avoided any glimpse in the mirror. Tentatively, I padded back down the corridor in my bare but clean feet.

In the room, more treasures awaited. Clean underwear was draped over the chair, along with a skirt, stockings and a sweater. There was an undervest but no bra, though I had nothing to keep in check any more, with almost the look of a pubescent teenager on a prematurely aged body. Within minutes, Christa arrived with a plate of glazed meat, potatoes and carrots the colour of a late afternoon sun glowing alongside. Hunger was a constant gripe, and I hadn’t noticed not eating throughout the day.

‘I’ll leave you in peace,’ she said, with a sweet, natural smile. ‘I’ll bring in breakfast in the morning, and Madam will see you after that.’

My instinct was to go at that plate like a gannet, gorging on the precious calories, but I knew enough of my starved insides to guess that, if I wanted to retain it and not retch it up instantly, I needed to tread carefully. I chewed and savoured each morsel, quickly feeling the stretch inside me. Once or twice, my throat gagged uncontrollably at the richness, and I breathed deeply, desperate to swallow it down. The meat, softly stewed, brought back memories from before the war, of my mother’s birthday meals – beef with German ale. Guiltily, though, I had to leave a third of the portion. With nothing else to occupy me, I laid my wet hair on the sumptuous pillow, drinking in the laundry soap smell, and fell into an immediate sleep.

Light from a small window above the bed signalled daytime, and I moved my shoulder slowly, as I had done every day in previous months. My wooden bed rack had caused painful sores on my shoulders, and getting up demanded restraint to avoid opening up the skin and inviting infection. Only when I felt my skin sunk into soft cotton did I remember where I was. Even then it took several moments to convince my waking brain that I wasn’t lost in a fantasy.

The noise of a house in full motion crept through the walls and I tiptoed to the bathroom, feeling the inevitable grapple inside me between starvation and distension. Christa was heading into my room as I arrived back, wearing a slightly startled look, as if she had lost me momentarily. As if I could escape.

‘Morning, Fräulein,’ she said, addressing me like a true guest. I had warmed to her already, mainly for treating me like a human being, and because she had brought me more food. Her flaxen hair was pulled tight into a bun, making her high cheekbones rise and her green eyes sparkle.

‘I’m sorry, I couldn’t quite finish the dinner,’ I said, as she eyed the leftovers. ‘I’m not so use—’

‘Of course,’ she said with a smile. The staff clearly had their suspicions, whatever they had been told. It took me a good while to absorb the eggs and bread on my plate, yolks the colour of the giant sunflowers swaying in my mother’s garden. Memories, carefully kept in check while at the camp, were swimming back. I forced the protein into my already overloaded system and Christa was at the door as I pushed in the last mouthful.

She led me upstairs to a large lounge, skirted on three sides by wide picture windows, a view of the forest in one, mountains in the opposite. It was roomy enough for several leather sofas in an austere German design, with sideboards of dark wood and ugly, showy trinkets. The inevitable portrait of the Fuhrer loomed over the huge fireplace, which provided a gentle lick rather than a roar.

A woman was sitting in one of the bulky armchairs and stood as I arrived. Tall, slim and elegant, her blonde hair swept in a wave, clear blue eyes, and a pout of ruby red lipstick. Groomed and very German. Not obviously pregnant either.

‘Fräulein Hoff, welcome to my house.’ There was only a hint of a smile; from the very outset this was clearly an arrangement, and not one she was overly happy with either.

‘My name is Magda Goebbels, and I have been asked by a very good friend to find someone with your knowledge to help her.’

At the mere mention of her name, I realised why I had been treated so well. Frau Goebbels was the epitome of German womanhood, married to the Minister for Propaganda and mother to seven perfect Aryan specimens – an obvious model for those zealous posters. Since the Fuhrer had no wife, she was often at his side in the newsreels and pictures, in the time before I was taken. She was the perfect Nazi, albeit a woman, tagged ‘Germany’s First Lady’ by the columnists.

She went on matter-of-factly. ‘I know of your reputation, your working knowledge, and your … situation.’ I noted there was always a pause when the threat to my family was mentioned. Was it shame, or a minor embarrassment? For people so unashamed about the cruelty they inflicted, Nazis appeared almost shy about calling it blackmail.

She carried on, unabashed: ‘I know that since your work has been so varied, you clearly care deeply for women and babies in any situation. I can only trust that you will do the same for my friend who has need.’ She paused, inviting a reply.

‘I will always endeavour to bring the best outcome for any woman,’ I said, leaving my own, deliberate pause. ‘Whoever they are.’ I did, in essence, mean it. The rules of my training as a midwife didn’t discriminate between rich or poor, good or bad, criminal or good citizen; all babies were born equal at that split second and all deserved the chance of life. It was the moments, months and years afterwards that fractured them into an unequal world.