Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

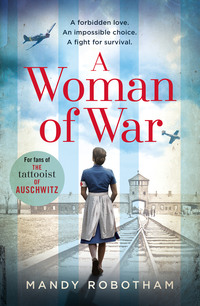

Kitabı oku: «A Woman of War», sayfa 5

9

Contact

A week later, Eva asked me to walk with her again. The day was crisp, but the air heavier with mist and her mood was dampened, though she made an effort to keep the conversation flowing.

‘So, do you think you will ever have children, Fräulein Hoff? I mean, your position – seeing what you do – it hasn’t put you off?’

I was slightly taken aback at her frankness, as we hadn’t broached anything so personal before. She might have known from my files that I was only a year younger than she, and still capable of having a baby, assuming camp life hadn’t rotted my insides – I hadn’t had a monthly cycle in over a year.

‘I hope one day to have a baby,’ I said. ‘I’m certainly not put off, or frightened, of it. Far from it. I think – I hope – I would relish it, welcome the experience. My work has taught me to have great faith in women. Mother Nature seems to get it right most times.’

‘I hope she’ll be kind to me,’ Eva Braun countered in a wistful voice. ‘I really do.’

I couldn’t tell if she was talking of the birth, the baby or both; the pressure on her to produce a consummate heir must have been sitting heavily even then. Nothing less than perfection would be tolerated.

‘And of course, the reward for a hard labour is always the baby,’ I said to lighten the mood, but as the words emerged, I thought instantly of the mothers who hadn’t been allowed to keep their prize, and I was ashamed of coating this dirty business with an acceptable sheen. How could I have forgotten so quickly? So easily? I was hit squarely by a swell of contrition and I coloured with the shame.

Eva Braun, however, heard only the gloss. ‘Oh! I’m so glad to hear that. My mother talked of childbirth being so positive, “powerful” she once said. I hope I feel that way when the time comes.’

‘And your family, are they excited?’

The pause in her step told me I’d gone too far, but Eva’s Reich standing did not turn on me. Instead, she pulled up her shoulders and assumed the facade.

‘Gretl is very excited. In fact, she’s coming in a few days, so you’ll get to meet her. I’m hoping she’ll be there at the birth.’

Her false chirpiness spoke volumes. The shroud of secrecy meant only her closest relatives would know – parents and siblings – and if they were enthusiastic Nazis, they would be proud beyond words. But if they were going through the motions of Third Reich belief, as I knew many families in Berlin had been, well versed in etiquette as a survival technique, they would fear for their daughter as well as themselves. I had heard some of the servants talking about Eva as if she weren’t worthy of her place at the Berghof, questioning what or who her family were – I put that down to envy and jealousy, since almost all seemed loyal supporters of their master. I wondered then if her parents regretted their daughter’s place in the inner circle.

Fräulein Braun cut short our walk, saying she urgently needed to write some letters before lunch.

‘I expect you do, too?’ she said.

I toyed with letting it go, but the lack of contact with my family rankled, especially since news of their wellbeing had appeared to be part of the agreement. And yet Sergeant Meier was always terribly busy whenever I tried asking him.

‘I’m afraid I’m not allowed letters, either in or out,’ I said flatly.

‘Oh … I hadn’t realised. I’m sorry.’ She flushed red, embarrassed, and turned in to the house.

After a minute or so, I went in through the servants’ entrance, and made my way to Frau Grunders’ parlour to choose a new book. There was the usual kitchen bustle but her room was quiet. Through the ceiling I heard voices, agitated and urgent. I caught only the edge of some words, muffled sounds – Fräulein Braun’s voice and the distinctive whine of Sergeant Meier.

‘I will have to … only the Captain can say …’ The words faded in and out.

‘I would be grateful … as soon as …’

I cocked my ear to tune further in to the sound, intently curious. I had never seen them in the same room before, and Sergeant Meier’s office and Eva’s room were on opposite sides of the house.

‘I will arrange …’

‘Thank you …’

A chair scraped overhead, that unmistakable click of heels and then silence.

I was returning to my room when Sergeant Meier caught up with me.

‘Ah! Fräulein Hoff.’

‘Morning, Sergeant Meier, and how are you?’ My amusement over the weeks had been in appearing as sweet and courteous to this odious man as I could bear to – my reward being his visible, sweaty discomfort.

‘I’m perfectly well, Fräulein. I have some news for you.’

‘Yes? My family?’ I was quick to presume.

‘Not yet, but I hope soon. It has been decided that you may write some letters, to your family if you wish. Or your friends.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘That comes as a surprise. I thought my work here wasn’t to be spoken of.’ I smiled innocently.

‘There will be no mention of your work, of course,’ he said, forehead glistening. ‘Just that you are well. You could talk about the weather, or how well the war is going, but no details. Each letter will, of course, be reviewed by myself.’

‘I wouldn’t expect any less, Sergeant Meier. How many letters am I permitted to write, and what should I write on?’

Sergeant Meier had already driven home that the small ledger and some loose paper I had been given were to be used only for my clinical reports on Fräulein Braun. Keeping a diary was not permitted.

‘No more than two per week, and I will arrange for you to have ample paper and envelopes,’ he said, a tiny bead of perspiration snaking towards one eyebrow. ‘If you put the letters into my office, I will see that they are forwarded, and any replies are given to you. And I will expect your monthly report on my desk soon – Captain Stenz will be visiting to collect your copy.’

I virtually ran all the way to my room, stepped inside the door and hugged myself, a broad smile turning into a laugh. A letter! The prospect of some news in return was so exciting. I realised then how isolated I had felt in recent weeks, with no friends to confide in or physical contact with anyone. Clearly, Eva Braun had engineered this change, either as a genuine act of friendship, some pity on her part, or as a way to engage my favour. The truth was, I didn’t care. I wasn’t too proud to accept her help if it meant I could know my family were alive. And if they were dead I wanted to know, I really did. To stop the hoping, the endless, unknown void.

The paper and envelopes duly arrived in my room that same afternoon – sheets of thick, grainy parchment, each stamped with the eagle icon of the Third Reich. I sat down to write to my parents, a letter each since it was almost certain they weren’t together, likely in different camps. What on earth to write? How to describe my state of mind – that constant, fizzing thread of anxiety that jolts you out of sleep at three a.m., to stare at the ceiling for hours on end, when you wonder what on earth you are doing, and how you might survive? How to convey meaning in a message in which even the words have bars?

I concentrated on making the tone of my news positive, relaying that I was at least out of danger – for now. When our lives in Berlin had become ever more precarious, my father and I had created a loose code between us. We’d settled on two words to signal our wellbeing; any mention of ‘sunshine’ meant we were safe, in relative terms, but greying ‘clouds’ or a ‘flat horizon’ signalled the opposite.

I wrote that I was fine, eating well – very true at that point – and that the sunshine was making me feel upbeat. ‘The horizon is sometimes quite bright, Papa,’ I rambled on, desperate to convey something he could interpret, not quite safe yet not in imminent danger. The rest was padded out with, ‘I hope you and Mother are well, I think of you and Franz and Ilse every day.’ If my father’s mind remained sharp, he would find a way of reading between the lines. And I had to rely on his faith, to know that, despite the notepaper, I had not become a zealous Nazi. I had not turned.

I was wrapped in a blanket on my porch and fighting against the dying light when I heard footsteps. Engrossed in my novel, I didn’t look up.

‘Goethe? I’m impressed.’

‘Captain Stenz,’ I said in greeting. ‘Do you need to see me? Would you like me to come into the house?’

‘No, no,’ he said, taking off his cap, ‘I don’t want to disturb you. But I would like a brief talk. May I?’ He gestured at the second chair. His tone suggested I wasn’t due for any rebuke, and his manner seemed relaxed as he sat.

‘Of course.’ I was glad of the company and yes, I was actually pleased to see him. Was it merely because he wasn’t Sergeant Meier? The Captain wore the same uniform, and yet my reaction to the man inside was entirely different.

He sat, turning his gaze and squinting as the sun slipped behind snow-capped mountains to the right of our view. I watched his eyes glaze over for a few seconds, then heard a sigh slip from between his lips, before the noise pulled him to attention.

‘So, how are you getting on? Are you being treated well, and do you have everything you need?’

‘Yes, I am well looked after,’ I assured him. ‘I have everything I need to do my job.’ I watched him catch my meaning.

‘Fräulein Braun tells me she is very happy with the arrangement, and says she is feeling well, so we can be grateful for that.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘She’s in good health. In fact, I feel rather underemployed. It’s not what I’m used to.’ We both seemed aware of exchanging niceties that said very little.

‘I wouldn’t be too concerned about that,’ he said, smiling. ‘Your value will be in the later stages, I have no doubt. It’s an important job.’

His eyes turned again to the horizon. The sun was dropping rapidly behind the peaks, white against the orange blaze. I fingered the pages of my book, looking at his blond hair cut neatly into the nape of his black collar, but which might have turned to curls if left to grow. From the neck up he looked like a boy from the country, and not a man who carried power in the threads of iron-grey below.

I wondered why he didn’t just up and leave, since he clearly had nothing else to say. It was me who sliced the silence, preventing his sudden departure.

‘Captain Stenz, can I ask you something?’

His fair head swivelled and he looked faintly alarmed. ‘You can ask, although I can’t promise to answer.’ Suddenly, he was SS again.

‘Well, I understand that secrecy is a safety issue with Fräulein Braun, given what I believe the bloodline to be—’ he flashed a look but didn’t contradict ‘—yet no one aside from a small number of people has acknowledged this baby. No one seems to be welcoming this news. The Third Reich believes in families, in large families. And I have worked at a Lebensborn before – before all of this. I know unmarried mothers are tolerated when it comes to helping … the cause.’ The words caught in my throat. ‘So I don’t understand this show of fake ignorance. This baby will be born, and then it will be difficult to hide. Shouldn’t they be happy as a couple? Wouldn’t it boost morale for the war if the country knew?’

He took a deep breath, and clasped his gloved fingers together. ‘It’s complicated, Fräulein Hoff, and I don’t pretend to be an expert in public relations – we have a department for that.’ He gave a resigned smile. ‘You give me too much credit – I am simply an engineer and a messenger, nothing more.’

‘So what are you an expert in?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I mean, what did you do, before the war?’ Finally, I was engaged in a discourse that didn’t feel submissive or dangerous.

‘I was a student of architecture. I had to give up my studies.’

‘Had to?’

‘It was expected,’ he said.

‘And will you go back to them? After, I mean?’

‘That depends.’

‘On what?’

‘On whether I live through the war,’ he said, dropping his smile. ‘And whether there is a world left to rebuild.’ He stood up, almost wary he might have let his guard slip. ‘I must go. If I could have your reports, Fräulein Hoff?’

‘Certainly,’ and I brought them from inside the door.

‘Goodbye, until next time,’ he said, and clicked his heels, stopping short of the salute. He replaced it with a nod of his head, although his eyes held mine. I watched his long shadow disappear towards the house, and felt suddenly very lonely.

10

Visitors

The following days saw a dramatic change in the calm of the Berghof. At breakfast the next morning there was a palpable tension, and the kitchen was unusually noisy and busy, the kitchen porter unloading a large delivery from the town. Frau Grunders drank her morning tea in gulps, rushing out and barking at the under-maids as she went. I heard them grumbling about ‘More work than we’re paid for, just for his majesty’s pleasure,’ but scurrying nonetheless.

I guessed what might be happening, and a sickening ache rippled among my innards. During the past weeks, I had thought little of the master of the house as a real entity – the war felt so far away, and he was out of sight, out of mind. And that suited me. I hadn’t wanted to consider coming into real contact, what I would say or do, or how I would behave. Outward dissent would be stupid, fatal even, yet anything less would also make me feel like a traitor – to my family, and our friends before the war, all those women suffering in the camp, all those babies whose birth and death days fell on the same date.

The excitement in the household was reflected in Fräulein Braun. She was agitated, enthusiastic and unusually flighty – she had clearly been reviewing her wardrobe before I arrived, and was teasing her hair out to a more natural style, moving like a child unable to contain her excitement. She was keen for me to listen to the heartbeat, but impatient to postpone the other checks.

‘I feel fine – can we do that tomorrow?’ she said.

I tried smiling, as if I understood her eagerness to be with her loved one, but my sentiment was entirely selfish; the less time I spent in the house the better for me. As I was leaving Frau Grunders stopped me, suggesting I take meals in my room over the next week ‘as we’ll all be very busy’. To me, it signalled the connivance over Eva’s baby was complete. Excepting Eva, the entire Berghof was in denial about the pregnancy. How did Herr Hitler feel, I pondered, about fatherhood to one human as well as an entire nation? I could only assume he didn’t share the same excitement as the baby’s mother. And what would that mean for the child’s future, and Eva’s?

He arrived later that afternoon, the throaty rumble of engines drawing me onto my porch. An army truck led the cavalcade of cars sweeping up the drive, spitting gravel as they swooped in. The truck held regular troops, who fanned out around the perimeter fence, guns cocked and ready. The first cars spilled out several army officers in green, followed by SS officers in their contrasting slate jackets, perfect ebony boots reflecting the afternoon glare. It was the fifth or sixth car that ground to a halt, and sat idling while the officers formed a semi-circle around. The cluster stopped me from seeing him emerge, but I could tell by the wave of deference that he was out of the car and standing. I didn’t spy the blond, capped head of Captain Stenz among them, and part of me was glad I couldn’t see him bowing and scraping. My stomach churned, mouth empty of saliva, and I wanted to peel my eyes away, but somehow I couldn’t. It was hard to take in, that a few hundred yards away was a man who held so much of the world in his palm, and whose fingers could fold over and crush it, on a whim. Not just me or my family, but anyone he wanted, anywhere. Not for the first time I pitied Eva Braun, for all her blind love and faith.

She was, by this point, at the top of the small flight of stairs leading up to the porch. Hair loose and face almost scrubbed free of make-up, she wore a traditional blue dress gathered at the bust, which had the effect of hiding her bump. Unusually, Negus and Stasi weren’t at her feet, as she had already told me they didn’t get on with Blondi, the Fuhrer’s own beloved Alsatian; Blondi’s size and status took precedence at the Berghof. The look of expectation on her face, of a child wanting to please, was almost pitiful.

He walked slowly up the stairs and planted a friendly kiss on her cheek; hardly the embrace of long-lost lovers eager to be alone. They turned and went inside together, and the uniformed entourage followed – I spied the hollowed features of Herr Goebbels in the group – while the troops encircled the house. The fortress was complete.

For the first time since my arrival at the Berghof, I had a desperate urge to run as fast as my legs would carry me away from this infected oasis. That feeling of uneasiness, which had smouldered in the pit of my belly since arrival, was now stoked to an inferno and I wanted so much to escape, even if it meant a life of uncertain danger. But I didn’t. Fear of reprisal kept me sitting, rooted to my chair, doing as I was told. And, not for the first time, I hated myself for it.

After eating in my room, I sat out late on my porch, reading at first and then just watching as the light died. The house itself became more illuminated, and sounds of male laughter drifted out into the mountain air. Down there, across the world, thousands – millions – of people were sobbing, screaming and dying, and all I could hear was amusement. I went to bed and rammed the pillow against my ears, desperate to shut out all the wrong in this mad arena called life.

11

The First Lady

Eva sent word the next morning to see her at eleven a.m. on the terrace – relief washed over me that I may not need to enter the house at all; the Fuhrer was hosting an important war conference, and the Berghof would be full of the green and grey for some time.

The day was glorious, a rich sun climbing in the sky as I skirted the house. Its brightness blotted out a good deal of the increasing green below, only the cobalt of several lakes breaking through. Fortunately, the terrace appeared almost empty, aside from Eva sitting under a large sun umbrella, sipping tea. Facing her, with neat blonde crown visible to me, was another woman. I assumed it was her sister, Gretl, who had come to the Berghof with her fiancé. They appeared deep in conversation as I approached.

‘Morning, Fräulein Braun,’ I ventured.

‘Ah, Fräulein Hoff, good morning,’ she said. ‘Thank you for delaying our meeting. You’ve met Frau—’ and as I rounded the chair I saw it was the head of Magda Goebbels, her blonde style faultless in its design, her face with limited make-up but the familiar ruby lips. She made a small attempt at a smile but stopped short of making it friendly.

‘Yes. Yes, Frau Goebbels and I have met.’ I was taken aback and it showed.

‘Please, sit down, Fräulein Hoff,’ said Frau Goebbels, taking immediate control and looking comfortable with it. ‘We – I – have a favour to ask.’

I smiled, still mildly amused that they could think of anything as a favour, as if a request meant I had a right to refuse.

‘First of all, I want to thank for your care of Fräulein Braun so far – she has been most complimentary about your skills.’ She took a long drag on her cigarette. Eva merely looked uncomfortable, as if she was a child being spoken for, while I felt like a favoured slave – it was a knack that Frau Goebbels had perfected. Her eyes met with yours for a split second, but she drew them away just as swiftly, giving the impression you were worthy of her attention, but not of maintaining it.

She went on. ‘But since she is in such good health, and does not need your services daily, I wonder if we might borrow you for a few days?’

What was I expected to say – ‘Let me think about it’? I said what they wanted to hear. ‘If Fräulein Braun is agreeable, then I will go where I can be most helpful.’

This time Magda Goebbels smiled fully, stubbing out her cigarette. She turned her attention on me, as if delivering orders.

‘A cousin of mine is preparing to have her baby. She has reached her due date and beyond, but she is being … well … in all honesty, I think she is being rather difficult, and refusing to leave the house to go into hospital. However, I am not her mother, and therefore the only influence I can bring upon her is to offer what help I can.’

I found it odd that she had thought of me, but I was equally irritated at being the hired help. From somewhere inside, a small chink of courage rose out of the annoyance.

‘Frau Goebbels, with all due respect, I am happy to help any woman, but I am not the type of midwife to force anyone into treatment they don’t want or need.’

Her wide eyes were on mine in seconds, fixed and fiery. Then, the familiar break away.

‘No, no obviously,’ she acquiesced. ‘We simply wanted an experienced midwife to attend her at home. I’m hoping a week at the most. Is that reasonable, Eva?’ She swivelled towards her host. It was obvious this had not been sanctioned by the Reich, and was a favour on Eva’s part.

‘Of course, perfectly fine,’ she nodded like an obedient puppy.

The house was an hour away, and I was to leave early the next morning. Standing there, I calculated my current worth to Frau Goebbels had created a little bargaining power.

‘I will need someone with me to assist at the birth,’ I said. ‘Someone I can rely on.’

‘I daresay there will be a willing housemaid, or reliable servant,’ Frau Goebbels said dismissively, turning her gaze away.

‘I would like Christa to come with me,’ I said with conviction. ‘She’s very resourceful, and I feel she won’t panic.’

‘Christa? My Christa? But you hardly know her,’ Frau Goebbels reasoned.

‘But I trust her to help me when I ask,’ I said.

Perhaps she was bored with any potential confrontation, because Magda Goebbels agreed to my request – she would release Christa. Maybe she didn’t view it as a concession, a small triumph on my part, but I did. I went back to my room, relieved that I had been released from this house of war games, and that I would meet up again with the only person within miles I might one day call a friend. Or indeed, an ally.

I arranged to meet Fräulein Braun later that afternoon for an ante-natal check, given I might not see her for a week. Part of me also wanted to gauge her mood at this strange, unsettling time – we hadn’t exchanged more than a few words since the Fuhrer had come to the Berghof. In the house there had been low whispers on the fierce words coming from the Fuhrer’s apartment – his and Eva’s. I pretended to be absorbed but my ears were fixed on the maid’s tittle-tattle of tears and pleadings seeping from Eva’s room.

‘Lord forgive me, but what he called her was cruel,’ the maid said. ‘I wouldn’t want to be in her shoes, not even to be mistress of this place.’ The details were lost as they turned and walked away, but the meaning was clear. In their own domestic war, Eva’s baby had made her weaker instead of stronger.

That afternoon, Eva’s door was ajar and she was at her dressing table, grimacing at her own reflection. She looked weary. There were muddy puddles under her eyes, and her normally fair, vibrant skin seemed dry and rough. No wonder she was disapproving of what she saw.

‘If you don’t mind me saying, Fräulein Braun, you look tired. Is the baby keeping you awake?’

‘A little,’ she said. ‘An aunt of mine always said babies come alive at night, and this one seems to be no exception. Is that right?’

‘Yes, they don’t have any conception of day and night for a long while. Perhaps once you lie still the baby remembers it needs to move. Are you managing to nap during the day?’

‘Not right now, not while …’ she hesitated and chose her words ‘… not while the house is so busy.’

Still, we hadn’t managed to move beyond the spectre of Adolf Hitler. It was clear they were intimately involved – she was the only female who consistently had a virtual free rein at the Berghof, aside from Magda Goebbels – and Frau Goebbels’ barely suppressed jealousy was enough to signal the affair between Eva and Adolf. She was pregnant, and yet she couldn’t quite acknowledge out loud that he was the father. From what I had seen, the SS hierarchy barely acknowledged her worth, and yet she seemed glued to the place that was his creation, that contained a piece of his heart. Always supposing he had one.

We went through the motions of a check, and I listened to the fast rump, tump of her baby’s heart. This was when Eva’s face softened and became girl-like again. I was conscious of my face screwing up in concentration as I began, but I could feel it relax as the sounds came into my own ear, and her face too would spread in joy as I nodded that all was well.

‘I won’t be too far away, and if the baby hasn’t arrived within a week, I’ll request the chauffeur brings me back up, at least for a check,’ I told her.

‘Thank you,’ she said, with genuine gratitude. ‘That’s kind of you to think ahead. But I will be fine.’

In truth, I did feel sorry for her – she seemed so alone. Even her sister, Gretl, hadn’t appeared for this mountain war summit. The response that such a feeling stirred within me was hard to process. Eva Braun consorted with Adolf Hitler, willingly. She appeared to love him. How much sympathy was she worthy of – and how much was she making a very dangerous bed to lie on? In between all of this was the baby, a new life with a heart that was – for now – empty of all sin.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.