Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

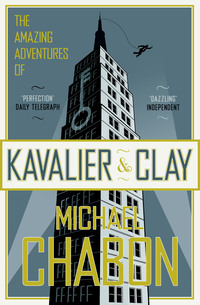

Kitabı oku: «The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay», sayfa 8

3

THE FIRST OFFICIAL MEETING of their partnership was convened outside the Kramler Building, in a nimbus compounded of the boys’ exhalations and of subterranean steam purling up from a grate in the pavement.

“This is good,” Joe said.

“I know.”

“He said yes,” Joe reminded his cousin, who stood patting idly with one hand at the front of his overcoat and a panicked expression on his face, as though worried that he had left something important behind in Anapol’s office.

“Yes, he did. He said yes.”

“Sammy.” Joe reached out and grabbed Sammy’s wandering hand, arresting it in its search of his pockets and collar and tie. “This is good.”

“Yes, this is good, god damn it. I just hope to God we can do it.”

Joe let go of Sammy’s hand, shocked by this expression of sudden doubt. He had been completely taken in by Sammy’s bold application of the Science of Opportunity. The whole morning, the rattling ride through the flickering darkness under the East River, the updraft of Klaxons and rising office blocks that had carried them out of the subway station, the ten thousand men and women who immediately surrounded them, the ringing telephones and gum-snapping chitchat of the clerks and secretaries in Sheldon Anapol’s office, the sly and harried bulk of Anapol himself, the talk of sales figures and competition and cashing in big, all this had conformed so closely to Joe’s movie-derived notions of life in America that if an airplane were now to land on Twenty-fifth Street and disgorge a dozen bathing-suit-clad Fairies of Democracy come to award him the presidency of General Motors, a contract with Warner Bros., and a penthouse on Fifth Avenue with a swimming pool in the living room, he would have greeted this, too, with the same dreamlike unsurprise. It had not occurred to him until now to consider that his cousin’s display of bold entrepreneurial confidence might have been entirely bluff, that it was 8°C and he had neither hat nor gloves, that his stomach was as empty as his billfold, and that he and Sammy were nothing more than a couple of callow young men in thrall to a rash and dubious promise.

“But I have belief in you,” Joe said. “I trust you.”

“That’s good to hear.”

“I mean it.”

“I wish I knew why.”

“Because,” said Joe. “I don’t have any choice.”

“Oh ho.”

“I need money,” Joe said, and then tried adding, “god damn it.”

“Money.” The word seemed to have a restorative effect on Sammy, snapping him out of his daze. “Right. Okay. First of all, we need horses.”

“Horses?”

“Arms. Guys.”

“Artists.”

“How about we just call them ‘guys’ for right now?”

“Do you know where we can find some?”

Sammy thought for a moment. “I believe I do,” he said. “Come on.”

They set off in a direction that Joe decided was probably west. As they walked Sammy seemed to get lost quickly in his own reflections. Joe tried to imagine the train of his cousin’s thoughts, but the particulars of the task at hand were not clear to him, and after a while he gave up and just kept pace. Sammy’s gait was deliberate and crooked, and Joe found it a challenge to keep from getting ahead. There was a humming sound everywhere that he attributed first to the circulation of his own blood in his ears before he realized that it was the sound produced by Twenty-fifth Street itself, by a hundred sewing machines in a sweatshop overhead, exhaust grilles at the back of a warehouse, the trains rolling deep beneath the black surface of the street. Joe gave up trying to think like, trust, or believe in his cousin and just walked, head abuzz, toward the Hudson River, stunned by the novelty of exile.

“Who is he?” Sammy said at last, as they were crossing a broad street which a sign identified, improbably somehow, as Sixth Avenue. Sixth Avenue! The Hudson River!

“Who is he,” Joe said.

“Who is he, and what does he do?”

“He flies.”

Sammy shook his head. “Superman flies.”

“So ours does not?”

“I just think I’d …”

“To be original.”

“If we can. Try to do it without flying, at least. No flying, no strength of a hundred men, no bulletproof skin.”

“Okay,” Joe said. The humming seemed to recede a little. “And some others, they do what?”

“Well, Batman—”

“He flies, like a bat.”

“No, he doesn’t fly.”

“But he is blind.”

“No, he only dresses like a bat. He has no batlike qualities at all. He uses his fists.”

“That sounds dull.”

“Actually, it’s spooky. You’d like it.”

“Maybe another animal.”

“Uh, well, yeah. Okay. A hawk. Hawkman.”

“Hawk, yes, okay. But that one must fly.”

“Yeah, you’re right. Scratch the bird family. The, uh, the Fox. The Shark.”

“A swimming one.”

“Maybe a swimming one. Actually, no, I know a guy works in the Chesler shop, he said they’re already doing a guy who swims. For Timely.”

“A lion?”

“Lion. The Lion. Lionman.”

“He could be strong. He roars very loud.”

“He has a super roar.”

“It strikes fear.”

“It breaks dishes.”

“The bad guys go deaf.”

They laughed. Joe stopped laughing.

“I think we have to be serious,” he said.

“You’re right,” said Sammy. “The Lion, I don’t know. Lions are lazy. How about the Tiger. Tigerman. No, no. Tigers are killers. Shit. Let’s see.”

They began to go through the rolls of the animal kingdom, concentrating naturally on the predators: Catman, Wolfman, the Owl, the Panther, the Black Bear. They considered the primates: the Monkey, Gorillaman, the Gibbon, the Ape, the Mandrill with his multicolored wonder ass that he used to bedazzle opponents.

“Be serious,” Joe chided again.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry. Look, forget animals. Everybody’s going to be thinking of animals. In two months, I’m telling you, by the time our guy hits the stands, there’s going to be guys running around dressed like every damn animal in the zoo. Birds. Bugs. Underwater guys. And I’ll bet you anything there’s going to be five guys who are really strong, and invulnerable, and can fly.”

“If he goes as fast as the light,” Joe suggested.

“Yeah, I guess it’s good to be fast.”

“Or if he can make a thing burn up. If he can—listen! If he can, you know. Shoot the fire, with his eyes!”

“His eyeballs would melt.”

“Then with his hands. Or, yes, he turns into a fire!”

“Timely’s doing that already, too. They got the fire guy and the water guy.”

“He turns into ice. He makes the ice everywhere.”

“Crushed or cubes?”

“Not good?”

Sammy shook his head. “Ice,” he said. “I don’t see a lot of stories in ice.”

“He turns into electricity?” Joe tried. “He turns into acid?”

“He turns into gravy. He turns into an enormous hat. Look, stop. Stop. Just stop.”

They stopped in the middle of the sidewalk, between Sixth and Seventh avenues, and that was when Sam Clay experienced a moment of global vision, one which he would afterward come to view as the one undeniable brush against the diaphanous, dollar-colored hem of the Angel of New York to be vouchsafed to him in his lifetime.

“This is not the question,” he said. “If he’s like a cat or a spider or a fucking wolverine, if he’s huge, if he’s tiny, if he can shoot flames or ice or death rays or Vat 69, if he turns into fire or water or stone or India rubber. He could be a Martian, he could be a ghost, he could be a god or a demon or a wizard or monster. Okay? It doesn’t matter, because right now, see, at this very moment, we have a bandwagon rolling, I’m telling you. Every little skinny guy like me in New York who believes there’s life on Alpha Centauri and got the shit kicked out of him in school and can smell a dollar is out there right this minute trying to jump onto it, walking around with a pencil in his shirt pocket, saying, ‘He’s like a falcon, no, he’s like a tornado, no, he’s like a goddamned wiener dog.’ Okay?”

“Okay.”

“And no matter what we come up with, and how we dress him, some other character with the same shtick, with the same style of boots and the same little doodad on his chest, is already out there, or is coming out tomorrow, or is going to be knocked off from our guy inside a week and a half.”

Joe listened patiently, awaiting the point of this peroration, but Sammy seemed to have lost the thread. Joe followed his cousin’s gaze along the sidewalk but saw only a pair of what looked to be British sailors lighting their cigarettes off a single shielded match.

“So …” Sammy said. “So …”

“So that is not the question,” Joe prompted.

“That’s what I’m saying.”

“Continue.”

They kept walking.

“How? is not the question. What? is not the question,” Sammy said.

“The question is why.”

“The question is why.”

“Why,” Joe repeated.

“Why is he doing it?”

“Doing what?”

“Dressing up like a monkey or an ice cube or a can of fucking corn.”

“To fight the crime, isn’t it?”

“Well, yes, to fight crime. To fight evil. But that’s all any of these guys are doing. That’s as far as they ever go. They just … you know, it’s the right thing to do, so they do it. How interesting is that?”

“I see.”

“Only Batman, you know … see, yeah, that’s good. That’s what makes Batman good, and not dull at all, even though he’s just a guy who dresses up like a bat and beats people up.”

“What is the reason for Batman? The why?”

“His parents were killed, see? In cold blood. Right in front of his eyes, when he was a kid. By a robber.”

“It’s revenge.”

“That’s interesting,” Sammy said. “See?”

“And he was driven mad.”

“Well …”

“And that’s why he puts on the bat’s clothes.”

“Actually, they don’t go so far as to say that,” Sammy said. “But I guess it’s there between the lines.”

“So, we need to figure out what is the why.”

“‘What is the why,’” Sammy agreed.

“Flattop.”

Joe looked up and saw a young man standing in front of them. He was short-waisted and plump, and his face, except for a pair of big black spectacles, was swaddled and all but invisible in an elaborate confection of scarf and hat and earflaps.

“Julius,” Sammy said. “This is Joe. Joe, this is a friend from the neighborhood, Julie Glovsky.”

Joe held out his hand. Julie studied it a moment, then extended his own small hand. He had on a black woolen greatcoat, a fur-lined leather cap with mammoth earflaps, and too-short green corduroy trousers.

“This guy’s brother is the one I told you about,” Sammy told Joe. “Making good money in comics. What are you doing here?”

Somewhere deep within his wrappings, Julie Glovsky shrugged. “I need to see my brother.”

“Isn’t that remarkable, we need to see him, too.”

“Yeah? Why’s that?” Julie Glovsky shuddered. “Only tell me fast before my nuts fall off.”

“Would that be from cold or, you know, atrophy?”

“Funny.”

“I am funny.”

“Unfortunately not in the sense of ‘humorous.’”

“Funny,” Sammy said.

“I am funny. What’s your idea?”

“Why don’t you come to work for me?”

“For you? Doing what? Selling shoestrings? We still got a box of them at my house. My mom uses them to sew up chickens.”

“Not shoelaces. My boss, you know, Sheldon Anapol?”

“How would I know him?”

“Nevertheless, he is my boss. He’s going into business with his brother-in-law, Jack Ashkenazy, who you also do not know, but who publishes Racy Science, Racy Combat, et cetera. They’re going to do comic books, see, and they’re looking for talent.”

“What?” Julie poked his tortoise face out from the shadows of its woolen shell. “Do you think they might hire me?”

“They will if I tell them to,” said Sammy. “Seeing as how I’m the art director in chief.”

Joe looked at Sammy and raised an eyebrow. Sammy shrugged.

“Joe and I, here, we’re putting together the first title right now. It’s going to be all adventure heroes. All in costumes,” he said, extemporizing now. “You know, like Superman. Batman. The Blue Beetle. That type of thing.”

“Tights, like.”

“That’s it. Tights. Masks. Big muscles. It’s going to be called Masked Man Comics,” he continued. “Joe and I’ve got the lead feature all taken care of, but we need backup stuff. Think you could come up with something?”

“Shit, Flattop, yes. You bet.”

“What about your brother?”

“Sure, he’s always looking for more work. They got him doing Romeo Rabbit for thirty dollars a week.”

“Okay, then, he’s hired, too. You’re both hired, on one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“We need a place to work,” said Sammy.

“Come on then,” said Julie. “I guess we can work at the Rathole.” He leaned toward Sammy as they started off, lowering his voice. The tall skinny kid with the big nose had fallen a few steps behind them to light a cigarette. “Who the hell is that guy?”

“This?” Sammy said. He took hold of the kid’s elbow and tugged him forward as though bringing him out onstage to take a deserved bow. He reached up to grab a handful of the kid’s hair and gave it a tug, just kind of rocking his head from side to side while holding on to his hair, grinning at him. Had Joe been a young woman, Julie Glovsky might almost have been inclined to think that Sammy was sweet on her. “This is my partner.”

4

SAMMY WAS THIRTEEN when his father, the Mighty Molecule, came home. The Wertz vaudeville circuit had folded that spring, a victim of Hollywood, the Depression, mismanagement, bad weather, shoddy talent, philistinism, and a number of other scourges and furies whose names Sammy’s father would invoke, with incantatory rage, in the course of the long walks they took together that summer. At one time or another he assigned blame for his sudden joblessness, with no great coherence or logic, to bankers, unions, bosses, Clark Gable, Catholics, Protestants, theater owners, sister acts, poodle acts, monkey acts, Irish tenors, English Canadians, French Canadians, and Mr. Hugo Wertz himself.

“Hell with ’em,” he would invariably finish, with a sweeping gesture that, in the dusk of a Brooklyn July, was limned by the luminous arc of his cigar. “The Molecule one day says ‘fuck you’ to the all of them.”

The free and careless use of obscenity, like the cigars, the lyrical rage, the fondness for explosive gestures, the bad grammar, and the habit of referring to himself in the third person were wonderful to Sammy; until that summer of 1935, he had possessed few memories or distinct impressions of his father. And any of the above qualities (among several others his father possessed) would, Sammy thought, have given his mother reason enough to banish the Molecule from their home for a dozen years. It was only with the greatest reluctance and the direct intervention of Rabbi Baitz that she had agreed to let the man back in the house. And yet Sammy understood, from the moment of his father’s reappearance, that only dire necessity could ever have induced the Genius of Physical Culture to return to his wife and child. For the last dozen years he had wandered, “free as a goddamn bird in the bush,” among the mysterious northern towns of the Wertz circuit, from Augusta, Maine, to Vancouver, British Columbia. An almost pathological antsiness, combined with the air of wistful longing that filled the Molecule’s simian face, petite and intelligent, when he spoke of his time on the road, made it clear to his son that as soon as the opportunity presented itself, he would be on his way again.

Professor Alphonse von Clay, the Mighty Molecule (born Alter Klayman in Drakop, a village in the countryside east of Minsk), had abandoned his wife and son soon after Sammy’s birth, though every week thereafter he sent a money order in the amount of twenty-five dollars. Sammy came to know him only from the embittered narratives of Ethel Klayman and from the odd, mendacious clipping or newspaper photo the Molecule would send along, torn from the variety page of the Helena Tribune, or the Kenosha Gazette, or the Calgary Bulletin, and stuffed, with a sprinkling of cigar ash, into an envelope embossed with the imprint of a drinking glass and the name of some demi-fleabag hotel. Sammy would let these accumulate in a blue velvet shoe bag that he placed under his pillow before he went to sleep each night. He dreamed often and intensely of the tiny, thick-muscled man with the gondolier mustachios who could lift a bank safe over his head and beat a draft horse in a tug-of-war. The plaudits and honors described by the clippings, and the names of the monarchs of Europe and the Near East who had supposedly bestowed them, changed over the years, but the essential false facts of the Mighty Molecule’s biography remained the same: ten lonely years studying ancient Greek texts in the dusty libraries of the Old World; hours of painful exercises performed daily since the age of five, a dietary regimen consisting only of fresh legumes, seafoods, and fruits, all eaten raw; a lifetime devoted to the careful cultivation of pure, healthy, lamblike thoughts and to total abstention from insalubrious and immoral behaviors.

Over the years, Sammy managed to wring from his mother scant, priceless drops of factual information about his father. He knew that the Molecule, who derived his stage name from the circumstance of his standing, in calf-high gold lamé buskins, just under five feet two inches tall, had been imprisoned by the Czar in 1911, in the same cell as a politically minded circus strong man from Odessa known as Freight Train Belz. Sammy knew that it was Belz, an anarcho-syndicalist, and not the ancient sages of Greece, who had schooled his father’s body and taught him to abstain from alcohol, meat, and gambling, if not pussy and cigars. And he knew that it was in Kurtzburg’s Saloon on the Lower East Side in 1919 that his mother had fallen in love with Alter Klayman, newly arrived in this country and working as an iceman and freelance mover of pianos.

Miss Kavalier was almost thirty when she married. She was four inches shorter than her diminutive husband, sinewy, grim-jawed, her eyes the pale gray of rainwater pooled in a dish left on the window ledge. She wore her black hair pulled into an unrelenting bun. It was impossible for Sammy to imagine his mother as she must have been that summer of 1919, an aging girl upended and borne aloft on a sudden erotic gust, transfixed by the vein-rippled arms of the jaunty homunculus who carried winking hundred-pound blocks of ice into the gloom of her cousin Lev Kurtzburg’s saloon on Ludlow Street. Not that Ethel was unfeeling—on the contrary, she could be, in her way, a passionate woman subject to transports of maudlin nostalgia, easily outraged, sunk by bad news, hard luck, or doctor’s bills into deep, black crevasses of despair.

“Take me with you,” Sammy said to his father one evening after dinner, as they were strolling down Pitkin Avenue, on their way out to New Lots or Canarsie or wherever the Molecule’s vagabond urges inclined him that night. Like a horse, Sammy had noticed, the Molecule almost never sat down. He cased any room he entered, pacing first up and down, then back and forth, checking behind the curtains, probing the corners with his gaze or the toe of a shoe, testing out the cushions in the chair or sofa with a measured bounce, then springing back onto his feet. If compelled to stand in one place for any reason, he would rock back and forth like someone who needed to urinate, worrying the dimes in his pocket. He never slept more than four hours a night, and even then, according to Sammy’s mother, with inquietude, thrashing and gasping and crying out in his sleep. And he seemed incapable of staying in any one place for longer than an hour or two at a time. Though it enraged and humiliated him, the process of looking for work, crisscrossing lower Manhattan and Times Square, haunting the offices of booking agents and circuit managers, suited him well enough. On the days when he stayed in Brooklyn and hung around the apartment, he drove everyone else to distraction with his pacing and rocking and hourly trips to the store for cigars, pens, a Racing Form, half a roast chicken—anything. In the course of their post-prandial wanderings, father and son ranged far and sat little. They explored the eastern boroughs as far as Kew Gardens and East New York. They took the ferry from the Bush Terminal out to Staten Island, where they hiked out of St. George to Todt Hill, returning well after midnight. When, rarely, they hopped a trolley or caught a train, they would stand, even if the car was empty; on the Staten Island Ferry, the Molecule prowled the decks like a character out of Conrad, uneasily watching the horizon. From time to time in the course of a walk, they might pause in a cigar shop or at a drugstore, where the Molecule would order a celery tonic for himself and a glass of milk for the boy and, disdaining the chrome stool with its Naugahyde seat, would down his Cel-Ray standing up. And once, on Flatbush Avenue, they had gone into a movie theater where The Lives of a Bengal Lancer was playing, but they stayed only for the newsreel before heading back out to the street. The only directions the Molecule disliked to venture were to Coney Island, in whose most evil sideshows he had long ago suffered unspecified torments, and to Manhattan. He had his fill of it during the day, he said, and what was more, the presence on that island of the Palace Theatre, the pinnacle and holy shrine of Vaudeville, was viewed as a reproach by the touchy and grudge-cherishing Molecule, who never had, and never would, tread its storied boards.

“You can’t leave me with her. It isn’t healthy for a boy my age to be with a woman like that.”

The Molecule stopped and turned to face his son. He was dressed, as always, in one of the three black suits that he owned, pressed and shiny with wear at the elbows. Though, like the others, it had been tailored to fit him, it nonetheless strained to encompass his physique. His back and shoulders were as broad as the grille of a truck, his arms as thick as the thighs of an ordinary man, and his thighs, when pressed together, rivaled his chest in girth. His waist looked oddly fragile, like the throat of an egg timer. He wore his hair cropped close and an anachronistic handlebar mustache. In his publicity photographs, where he often posed shirtless or in a skintight leotard, he appeared smooth as a polished ingot, but in street clothes he had an unwieldy, comical air and, with the dark hair poking out at his cuffs and collar, he looked like nothing so much as a pants-wearing ape, in a cartoon satirizing some all too human vanity.

“Listen to me, Sam.” The Molecule seemed taken aback by his son’s request, almost as though it dovetailed with his own thinking or, the thought crossed Sammy’s mind, he had been caught on the verge of skipping town. “Nothing makes me happier than I take you with me,” he continued, with the maddening vagueness his ill grammar permitted. He smoothed Sammy’s hair back with a heavy palm. “But then again, Jesus, what a crazy fucking idea.”

Sammy started to argue, but his father raised a hand. There was more to be said, and in the balance of his speech Sammy sensed or imagined a faint glimmer of hope. He knew that he had chosen a particularly auspicious night to make his plea. That afternoon, his parents had quarreled over dinner—literally. Ethel scorned the Molecule’s dietary regimen, claiming not only that the eating of raw vegetables had none of the positive effects her husband attributed to it but also that, every chance the man got, he was sneaking off around the corner to dine in secret on steak and veal chops and french-fried potatoes. That afternoon, Sammy’s father had returned to the apartment on Sackman Street (this was in the days before the move to Flatbush) from his afternoon of job hunting with a bag full of Italian squash. He dumped them out with a wink and a grin onto the kitchen table, like a haul of stolen goods. Sammy had never seen anything like these vegetables. They were cool and smooth and rubbed against one another with a rubbery squeak. You could see right where they had been cut from the vine. Their sliced-off stems, woody and hexagonal, implied a leafy green tangle that seemed to fill the kitchen along with their faint scent of dirt. The Molecule snapped one of the squashes in two and held its bright pale flesh up to Sammy’s nose. Then he popped one in his mouth and crunched it, smiling and winking at Sammy as he chewed.

“Good for your legs,” he had said, walking out of the kitchen to shower away the failures of the day.

Sammy’s mother boiled the squash until it was a mass of gray strings.

When the Molecule saw what she had done, there were sharp and bitter words. Then the Molecule had grabbed brusquely for his son, like a man reaching for his hat, and dragged Sammy out of the house and into the heat of the evening. They had been walking since six. The sun had long since gone down, and the sky to the west was a hazy moiré of purple and orange and pale gray-blue. They were walking along Avenue Z, dangerously close to the forbidden precincts of the Molecule’s early sideshow disasters.

“I don’t think you got the picture what’s it like out there for me,” he said as they walked along. “You think it’s like a circus in the pictures. All the clowns and the dwarf and the fat lady sitting around a nice big fire eating goulash and singing songs with an accordion.”

“I don’t think that,” Sammy said, though there was stunning accuracy in this assessment.

“If I did to take you with me—and I am just saying now if—you will have to work very hard,” the Molecule said. “They will only accept you if you can work.”

“I can work,” Sammy said, holding out an arm toward his father. “Look at that.”

“Yeh,” the Molecule said. He felt very carefully up and down the stout arms of his son, very much in the way Sammy had fingered the zucchini squash that afternoon. “You have arms that are not bad. But your legs are not so good.”

“Well, jeez, I mean, I had polio, Pop, what do you want?”

“I know you had polio.” The Molecule stopped again. He frowned, and in his face Sammy saw anger and regret and something else that looked almost like wishfulness. He stepped on his cigar end, and stretched, and shook himself a little, as if trying to shrug out of the constricting nets that his wife and son had thrown across his back. “What a fucking day I have. Holy shit.”

“What?” Sammy said. “Hey, where are you going?”

“I need to think,” his father said. “I need to think about what you are asking me.”

“Okay,” Sammy said. His father had started walking again, taking a right on Nostrand Avenue, striding along on his thick little legs with Sammy struggling to keep up, until he came to a peculiar building, Arabic in style, or maybe it was supposed to look Moroccan. It stood in the middle of the block, between a locksmith’s stall and a weedy yard stacked with blank headstones. Two skinny towers, topped with pointy dollops of peeling plaster, reached into the Brooklyn sky at either corner of the roof. It was windowless, and its broad expanse was clad, with weary elaboration, in a mosaic of small square tiles, fly-abdomen blue and a soapy gray that once must have been white. Many of the tiles were missing, chipped, or picked or tumbled loose. The doorway was a wide, blue-tiled arch. In spite of its forlorn appearance and hokum Coney Island air of the Mysterious East, there was something captivating about it. It reminded Sammy of the city of domes and minarets that you could just get a glimpse of, faint and illusory, behind the writing on the front of a pack of Chesterfields. Alongside the arched doorway, in letters of white tile bordered in blue, was written BRIGHTON GRAND HAMMAM.

“What’s a ham-mam?” Sammy said as they went in. His nose was immediately assaulted by a pungent odor of pine, by the smell of scorched ironing, damp laundry, and something deeper underneath it all, a human smell, salty and foul.

“It’s a shvitz,” the Molecule said. “You know what a shvitz is?”

Sammy nodded.

“When it’s time for thinking,” said the Molecule, “I like to have a shvitz.”

“Oh.”

“I hate thinking.”

“Yeah,” said Sammy. “Me too.”

They checked their clothes in the dressing room, in a tall black iron locker that creaked and fastened shut with the loud clang of a torture instrument. Then they went slapping down a long tiled corridor into the main steam room of the Brighton hammam. Their footsteps echoed as if they were inside a fairly large room. It was painfully hot, and Sammy felt that he couldn’t fill his lungs with sufficient air. He wanted to run back out to the relative cool of the Brooklyn evening, but he crept along, feeling his way through the billowing garments of steam, a hand on his father’s bare back. They climbed onto a low tiled bench and sat back, and Sammy felt each tile as a burning square against his skin. It was very hard to see, but from time to time a rogue current of air, or the vagaries of the invisible, wheezing, steam-producing machinery, would produce a break in the cover, and he could see that they were indeed inside a grand space, ribbed with porcelain groins, set with white and blue faience that was cracked in places, sweating and yellowed with age. As far as he could see, there were no other men or boys in the room with them, but he couldn’t be sure, and he felt obscurely afraid of an unknown face or naked limb suddenly looming out of the murk.

They sat for a long time, saying nothing, and at some point Sammy realized, first, that his body was producing veritable torrents of sweat with an abandon it had never before in his life displayed, and, second, that all along he had been imagining his existence in vaudeville: carrying an armload of spangled costumes down a long dark corridor of the Royal Theatre in Racine, Wisconsin, past a practice room where a piano tinkled and out the back door to the waiting van on a Saturday in midsummer, the deep midwestern night rich with june bugs and gasoline and roses, the smell of the costumes fusty but animated by the sweat and makeup of the chorus girls who had just vacated them, envisioning and inhaling and hearing all this with the vividness of a dream, though he was, as far as he could tell, wide-awake.