Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

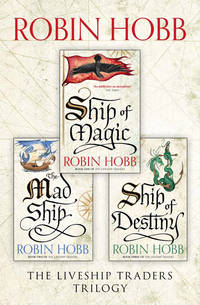

Kitabı oku: «The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny», sayfa 3

Kennit made a tiny movement of his shoulders and head, a movement that might mean yes or no, or nothing at all. He did not speak. Gankis shifted his feet about uncomfortably. The Other refilled its air sacs noisily.

‘That which the ocean washes up here is not for the keeping of men. The water brings it here because here is where the water wishes it to be. Do not set yourself against the will of the water, for no wise creature does that. No human is permitted to keep what he finds upon the Treasure Beach.’

‘Does it belong to the Other, then?’ Kennit asked calmly.

Despite the difference in species, it was still easy for Kennit to see he had disconcerted the Other. It took a moment to recover, then answered gravely, ‘What the ocean washes up upon the Treasure Beach belongs always to the ocean. We are but caretakers here.’

Kennit’s smile stretched his lips tight and thin. ‘Well then, you need have no concern. I’m Captain Kennit, and I’m not the only one who will tell you that all the ocean is mine to rove. So all that belongs to the ocean is mine as well. You’ve had your gold, now speak your prophecy, and take no more care for that which does not belong to you.’

Beside him Gankis gasped audibly, but the Other gave no sign of reacting to these words. Instead it bowed its head gravely, inclining its neckless body toward him, almost as if compelled to acknowledge Kennit as its master. Then it lifted its head and its fish eyes found Kennit’s soul as unerringly as a finger on a chart. When it spoke there was a deeper note to its voice, as if the words were blown up from deep inside it.

‘So plain this telling that even one of your spawn could read it. You take that which is not yours, Captain Kennit, and claim it as your own. No matter how much falls into your hands, you are never sated. Those that follow you must be content with what you have cast off as gew-gaws and toys, while you take what you perceive as most valuable and keep it for yourself.’ The creature’s eyes darted briefly to lock with Gankis’s goggling stare. ‘In his evaluations, you are both deceived, and both made the poorer.’

Kennit did not care at all for the direction of this soothsaying. ‘My gold has bought me the right to ask one question, has it not?’ he demanded boldly.

The Other’s jaw dropped open wide — not in astonishment, but perhaps as a sort of threat. The rows of teeth were indeed impressive. Then it snapped shut. The thin lips barely stirred as it belched out its answer. ‘Yesss.’

‘Shall I succeed in what I aspire?’

The Other’s air sacs pulsed speculatively. ‘You do not wish to make your question more specific?’

‘Do the omens need me to be more specific?’ Kennit asked with tolerance.

The Other glanced down at the array of objects again: the rose, the cups, the nails, the tumblers inside the ball, the feather, the crystal spheres. ‘You will succeed in your heart’s desire,’ it said succinctly. A smile began to dawn on Kennit’s face but faded as the creature continued, his tone growing more ominous. ‘That which you are most driven to do, you will accomplish. That task, that feat, that deed which haunts your dreams will blossom in your hands.’

‘Enough,’ Kennit growled, suddenly hasty. He abandoned any thought of asking for an audience with their goddess. This was as far as he wished to press their sooth-saying. He stooped to retrieve the prizes on the sand, but the creature suddenly fanned out its long-fingered webbed hands and spread them protectively above the treasures. A drop of venom welled greenly to the tip of each digit.

‘The treasures, of course, will remain on the Treasure Beach. I will see to their placement.’

‘Why, thank you,’ Kennit said, his voice melodic with sincerity. He straightened slowly, but as the creature relaxed its guard, he suddenly stepped forward, planting his foot firmly on the glass ball with the tumblers inside. It gave way with a tinkle like wind chimes. Gankis cried out as if he’d slain his first-born and even the Other recoiled at the wanton destructiveness. ‘A pity,’ Kennit observed as he turned away. ‘But if I cannot possess it, why should anyone?’

Wisely, he forbore a similar treatment for the rose. He suspected its delicate beauty was created from some material that would not give way to his boot’s pressure. He did not wish to lose his dignity by attempting to destroy it and failing. The other objects had small value in his regard; the Other could do whatever it wished with such flotsam. He turned and strode away.

Behind him he heard the Other hiss its wrath. It took a long breath, then intoned, ‘The heel that destroys that which belongs to the sea shall be claimed in turn by the sea.’ Its toothy jaws shut with a snap, biting off this last prophecy. Gankis immediately moved to flank Kennit. That one would always prefer the known danger to the unknown. Half a dozen strides down the beach, Kennit halted and turned. He called back to where the Other still crouched over the treasures. ‘Oh, yes, there was one other omen that perhaps you might wish to consider. But methinks the ocean washed it to you, not me, and thus I left it where it was. It is well known, I believe, that the Others have no love for cats?’ Actually, their fear and awe of anything feline was almost as legendary as their ability to sooth-say. The Other did not deign to reply, but Kennit had the satisfaction of seeing its air sacs puff with alarm.

‘You’ll find them up the beach. A whole litter of kits for you, with very pretty blue coats. They were in a leather bag. Seven or eight of the pretty little creatures. Most of them looked a bit poorly after their dip in the ocean, but no doubt those I let out will fare well. Do remember they belong, not to you, but the ocean. I’m sure you’ll treat them kindly.’

The Other made a peculiar sound, almost a whistle. ‘Take them!’ it begged. ‘Take them away, all of them. Please!’

‘Take away from the Treasure Beach that which the ocean saw fit to bring here? I would not dream of it,’ Kennit assured him with vast sincerity. He did not laugh, nor even smile as he turned away from its evident distress. He did find himself humming the tune to a rather bawdy song currently popular in Divvytown. The length of his stride was such that Gankis was soon puffing again as he trotted along beside him.

‘Sir?’ Gankis gasped. ‘A question if I might, Captain Kennit?’

‘You may ask it,’ Kennit granted him graciously. He half-expected the man to ask him to slow down. That he would refuse. They must make all haste back to the ship if they were to work her out to sea before the rocks emerged from the retreating tide.

‘What is it that you’ll succeed in doing?’

Kennit opened his mouth, almost tempted to tell him. But no. He had schemed this too carefully, staged it all in his mind too often. He’d wait until they were underway and Gankis had had plenty of time to tell all the crew his version of events on the island. He doubted that would take long. The old hand was garrulous, and after their absence the men would be eaten with curiosity about their visit to the island. Once they had the wind in their sails and were fairly back on their way to Divvytown, then he’d call all hands up on deck. His imagination began to carry him, and he pictured the moon shining down on him as he spoke to the men gathered below him in the waist. His pale blue eyes kindled with the glow of his own imaginings.

They traversed the beach much faster than they had when they were seeking treasure. In a short time they were climbing the steep trail that led up from the shore and through the wooded interior of the island. He kept well concealed from Gankis the anxiety he felt for the Marietta. The tides in the cove both rose and fell with an extremity that paid no attention to the phases of the moon. A ship believed to be safely anchored in the cove might abruptly find her hull grinding against rocks that surely had not been there at the last low tide. Kennit would take no chances with his Marietta; they’d be well away from this sorcerous place before the tide could strand her.

Away from the wind of the beach and in the shelter of the trees, the day was still and golden. The warmth of the slanting sunlight through the open-branched trees combined with the rising scents of the forest loam to make the day enticingly sleepy. Kennit felt his stride slowing as the peace of the golden place seeped into him. Earlier, when the branches had been dripping with the aftermath of the storm’s rain, the forest had been uninviting, a dank wet place full of brambles and slapping branches. Now he knew with unflagging certainty that the forest was a place of marvels. It had treasures and secrets every bit as tantalizing as those the Treasure Beach had offered.

His urgency to reach the Marietta peeled away from him and was discarded. He found himself standing still in the middle of the pebbled pathway. Today he would explore the island. To him would be opened the wonder-filled fey places of the Other, where a man might pass a hundred years in a single sublime night. Soon he would know and master it all. But for now it was enough to stand still and breathe the golden air of this place. Nothing intruded on his pleasure, save Gankis. The man persisted in chattering warnings about the tide and the Marietta. The more Kennit ignored him, the more he pelted him with questions. ‘Why have we stopped here, Captain Kennit? Sir? Are you feeling well, sir?’ He waved a dismissive hand at the man, but the old tar paid it no attention. He cast about for some errand that would take the noisy, smelly man from his presence. As he groped in his pockets, his hand encountered the locket and chain. He smiled slyly to himself as he drew it out.

He interrupted whatever it was Gankis was blithering about. ‘Ah, this will never do. See what I’ve accidentally carried off from their beach. Be a good lad now, and run this back to the beach for me. Give it to the Other and see it puts it safely away.’

Gankis gaped at him. ‘There isn’t time. Leave it here, sir! We’ve got to get back to the ship, before she’s on the rocks or they have to leave without us. There won’t be another tide that will let her back into Deception Cove for a month. And no man survives a night on this island.’

The man was beginning to get on his nerves. His loud voice had frightened off a tiny green bird that had been on the point of alighting nearby. ‘Go, I told you. Go!’ He put whips and fetters into his voice, and was relieved when the old sea-dog snatched the locket from his hand and dashed back the way they had come.

Once he was out of sight, Kennit grinned widely to himself. He hastened up the path into the island’s hilly interior. He’d put some distance between himself and where he’d left Gankis, and then he’d leave the trail. Gankis would never find him, he’d be forced to leave without him, and then all the wonders of the Others’ Island would be his.

‘Not quite. You would be theirs.’

It was his own voice speaking, in a tiny whisper so soft that even Kennit’s keen ears barely heard it. He moistened his lips and looked about himself. The words had shivered through him like a sudden awakening. He’d been about to do something. What?

‘You were about to put yourself into their hands. Power flows both ways on this path. The magic encourages you to stay upon it, but it cannot be worked to appeal to a human without also working to repel the Other. The magic that keeps their world safe from you also protects you as long as you do not stray from the path. If they persuade you to leave the path, you’ll be well within their reach. Not a wise move.’

He lifted his wrist to a level with his eyes. His own miniature face grinned mockingly back at him. With the charm’s quickening, the wood had taken on colours. The carved ringlets were as black as his own, the face as weathered, and the eyes as deceptively weak a blue. ‘I had begun to think you a bad bargain,’ Kennit said to the charm.

The face gave a snort of disdain. ‘If I am a bad bargain to you, you are as much a one to me,’ it pointed out. ‘I was beginning to think myself strapped to the wrist of a gullible fool, doomed to almost immediate destruction. But you seem to have shaken the effect of the spell. Or rather, I have cloven it from you.’

‘What spell?’ Kennit demanded.

The charm’s lip curled in a disdainful smile. ‘The reverse of the one you felt on the way here. All succumb to it that tread this path. The magic of the Other is so strong that one cannot pass through their lands without feeling it and being drawn toward it. So they settle upon this path a spell of procrastination. One knows that their lands beckon, but one puts off visiting them until tomorrow. Always tomorrow. And hence, never. But your little threat about the kittens has unsettled them a bit. You they would lure from the path, and use as a tool to be rid of the cats.’

Kennit permitted himself a small smile of satisfaction. ‘They did not foresee I might have a charm that would make me proof against their magic.’

The charm pressed its mouth. ‘I but made you aware of the spell. Awareness of any spell is the strongest charm against it. Of myself, I have no magic to fling back at them, or use to deaden their own.’ The face’s blue eyes shifted back and forth. ‘And we may yet both meet our destruction if you stand about here talking to me. The tide retreats. Soon the mate must choose between abandoning you here or letting the Marietta be devoured by the rocks. Best you hasten for Deception Cove.’

‘Gankis!’ Kennit exclaimed in dismay. He cursed, but began to run. Useless to go back for the man. He’d have to abandon him. And he’d given him the golden locket as well! What a fool he’d been, to be so gulled by the Others’ magic. Well, he’d lost his witness and the souvenir he’d intended to carry off with him. He’d be damned if he’d lose his life or his ship as well. His long legs stretched as he pelted down the winding path. The golden sunlight that had earlier seemed so appealing was suddenly only a very hot afternoon that seemed to withhold the very air from his straining lungs.

A thinning of the trees ahead alerted him that he was nearly at the cove. Instants later, he heard the drumming of Gankis’s feet on the path behind him, and was shocked when the sailor passed him without hesitation. Kennit had a brief glimpse of his lined face contorted with terror, and then he saw the man’s worn shoes flinging up gravel from the path as he ran ahead. Kennit had thought he could not run any faster, but Gankis suddenly put on a burst of speed that carried him out of the sheltering trees and onto the beach.

He heard Gankis crying out to the ship’s boy to wait, wait. The lad had evidently decided to give up on his captain’s return, for he had pushed and dragged the gig out over the seaweed and barnacle-coated rocks to the retreating edge of the water. A cry went up from the anchored ship at the sight of Kennit and Gankis emerging onto the beach. On the afterdeck, a sailor waved at them frantically to hurry. The Marietta was in grave circumstances. The retreating tide had left her almost aground. Straining sailors were already labouring at the anchor windlass. As Kennit watched, the Marietta gave a tiny sideways list and then slid from on top of a rock as a wave briefly lifted her clear. His heart stood still in his chest. Next to himself, he treasured his ship above all other things.

His boots slipped on squidgy kelp and crushed barnacles as he scrambled down the rocky shore after the boy and gig. Gankis was ahead of him. No orders were necessary as all three seized the gunwales of the gig and ran her out into the retreating waves. They were soaked before the last one scrambled inside her. Gankis and the boy seized the oars and set them in place while Kennit took his place in the stern. The Marietta’s anchor was rising, festooned with seaweed. Oars battled with sails as the distance between the two craft grew smaller. Then the gig was alongside, the tackles lowered and hooked, and but a few moments later Kennit was astride his own deck. The mate was at the wheel, and the instant he saw his captain safely aboard, Sorcor swung the wheel and bellowed the orders that would give the ship her head. Wind filled the Marietta’s sails, and flung her out against the incoming tide into the racing current that would buffet her, but carry her away from the bared teeth of Deception Cove.

A glance about the deck showed Kennit that all was in order. The ship’s boy cowered when the captain’s eyes swept over him. Kennit merely looked at him, and the boy knew his disobedience would not be forgotten nor overlooked. A pity. The boy had had a sweet smooth back; tomorrow that would no longer be so. Tomorrow would be soon enough to deal with him. Let him look forward to it for a time, and savour the stripes his cowardice had bought him. With no more than a nod to the mate, Kennit sought his own quarters. Despite the near mishap, his heart thundered with triumph. He had bested the Others at their own game. His luck had held, as it always had; the costly charm on his wrist had quickened and proved its value. And best of all, he had the oracle of the Others themselves to give the cloak of prophecy to his ambitions. He would be the first King of the Pirate Isles.

2 LIVESHIPS

THE SERPENT FLOWED through the water, effortlessly riding the wake of the ship. Its scaled body shone like a dolphin’s, but more iridescently blue. The head it lifted clear of the water was wickedly quilled with dangling barbels like those on a ratfish. Its deep blue eyes met Brashen’s and widened in expectation like a woman’s when she flirts. Then the maw of the creature opened wide, brilliantly scarlet and lined with row upon row of inward slanting teeth. It gaped open, big enough to take in a standing man. The dangling barbs stood up suddenly around the serpent’s head, a lion’s mane of poisonous darts. The scarlet mouth came darting towards him to engulf him.

Darkness surrounded Brashen, and the cold carrion stench of the creature’s mouth. He flung himself away wildly with an incoherent cry. His hands met wood, and with the touch of it, relief flooded him. Nightmare. He drew a shuddering breath. He listened to the familiar sounds; the creaking of the Vivacia’s timbers, the breathing of other sleeping men and the slapping of the water against the hull. Overhead, he could hear the barefoot patter of someone springing to answer a command. All was familiar, all was safe. He took a deep breath of air thick with the scent of tarry timbers, the stink of men living long in close quarters, and beneath it all, faint as a woman’s perfume, the spicy smells of their cargo. He stretched, pushing his shoulders and feet against the cramped confines of his wooden bunk, and then settled back into his blanket. It was hours yet to his watch. If he didn’t sleep now, he’d regret it later.

He closed his eyes to the dimness of the forecastle, but after a few moments, he opened them again. Brashen could sense his dream lurking just beneath the surface of sleep, waiting to reclaim him and drag him down. He cursed softly under his breath. He needed to get some sleep, but there’d be no rest in it if all he did was drop back down into the depths of the serpent dream.

The recurrent dream was now almost more real to him than the memory. It came to trouble him at odd times, usually when he was facing some major decision. At such times it reared up from the depths of his sleep to fasten its long teeth into his soul and try to pull him under. It little mattered that he was a full man now. It mattered not at all that he was as good a sailor as any he’d ever shipped with, and better than nine-tenths of them. When the dream seized on him he was dragged back to his boyhood, back to a time when all, even himself, had rightly despised him.

He tried to decide what was troubling him most. His captain despised him. Yes, that was true, but it didn’t make him any less a seaman. He’d been mate on this ship under Captain Vestrit and had well proved his worth to that man. When Vestrit had taken ill, Brashen had dared to hope the Vivacia would be put into his hands to captain. Instead the old Trader had turned it over to his son-in-law Kyle Haven. Well, family was family, and Brashen could accept what had been done. Then Captain Haven had exercised his option of choosing his own first mate, and it hadn’t been Brashen Trell. Still the demotion was no fault of his own, and every sailor in the ship – no, every sailor in Bingtown itself had known that. No shame to it; Kyle had simply wanted his own man. Brashen had thought it over and decided he’d rather serve as second mate on the Vivacia than first on any other vessel. It had been his own decision and he could fault no one else for it. Even after they had left the docks and Captain Haven had belatedly decided that he wanted a familiar man as second, and Brashen could move down yet another notch, he had gritted his teeth and obeyed his captain. But despite his years with the Vivacia and his gratitude to Ephron Vestrit, he suspected this would be the last time he shipped on her.

Captain Haven had made it clear to him that he neither welcomed nor respected Brashen as a member of his crew. During this last leg of the journey, nothing he did pleased the captain. If he saw a task that needed doing and put men to work on it, he was told he’d overstepped his authority. If he did only the duties that were precisely assigned to him, he was told he was a lazy lackwit. With each passing day, Bingtown grew nearer, but Haven grew more abrasive as well. Brashen was thinking that when they tied up in their home port, if Vestrit wasn’t ready to step back on as captain again, Brashen would step off the Vivacia’s decks for the last time. It gave him a pang, but he reminded himself there were other ships, some of them fine ones, and Brashen had a name now as a good hand. It wasn’t like it had been when he’d first sailed and he’d had to take any berth he could get on any ship. Back then, surviving a voyage had been his highest priority. That first ship out, that first voyage, and his nightmare were all tied together in his mind.

He had been fourteen the first time he’d seen a sea serpent. It was ten long years ago now, and he had been as green as the grass stains on a tumble’s skirts. He’d been less than three weeks aboard his first ship, a wallowing Chalcedean sow called the Spray. Even in the best of water she moved like a pregnant woman pushing a barrow, and in a following sea no one could predict where the deck would be from one moment to the next. So he’d been seasick, and sore, both from the unaccustomed work and from a well-earned drubbing from the mate the night before. Sore in spirit, too, for in the dark that slimy Farsey had come to crouch by him as he slept in the forepeak, offering him words of sympathy for his bruises and then a sudden hand groping under his blanket. He’d rebuffed Farsey, but not without humiliation. The tubby sailor had a lot of muscle underneath his lard, and his hands had been all over Brashen even as the boy had punched and pummelled and writhed away from him. None of the other hands sleeping in the forepeak had so much as stirred in their blankets, let alone offered to aid him. He was not popular with the other sailors, for his body was too unscarred and his language too elevated for their tastes. ‘Schoolboy’ they called him, not guessing how that stung. They knew they couldn’t trust him to know his business, let alone do it, and a man like that aboard a ship is a man who gets other men killed.

So when he fled the forepeak and Farsey, he went to the afterdeck to sit huddled in his blanket and sniffle a bit to himself. The school and masters and endless lessons that had seemed so intolerable now beckoned to him like a siren, recalling him to soft beds and hot meals and hours that belonged to him alone. Here on the Spray if he was seen to be idle, he caught the end of a rope. Even now, if the mate came across him, he’d either be ordered back below or put to work. He knew he should try to sleep. Instead he stared out over the oily water heaving in their wake and felt an answering unrest in his own belly. He’d have puked again, if there had been anything left to retch up. He leaned his forehead on the railing and tried to find one breath of air that did not taste of either the tarry ship or the salt water that surrounded it.

It was while he was looking at the shining black water rolling so effortlessly away from the ship that it occurred to him he had one other option. It had never presented itself to him before. Now it beckoned to him, simple and logical. Slip into the water. A few minutes of discomfort, and then it would all be over. He’d never have to answer to anyone again, or feel the snap of a rope against his ribs. He’d never have to feel ashamed or frustrated or stupid again. Best of all, the decision would only take an instant, and then it would be done. There’d be no agonizing over it, not even a prayer of undoing it. One moment of decisiveness would be all he’d have to find.

He stood up. He leaned over the railing, searching within himself for that one moment of strength to seize control of his own fate. But as he took that one great breath to find the will to tumble over the rail, he saw it. It slipped along, silent as time, its great sinuous body concealed in the smooth curve of water that was the wake of the ship. The wall of its body perfectly mimicked the arch of the moving water: but for the betraying moonlight showing him a momentary flank of glistening scales, Brashen would never have known the creature was there.

His breath froze in his chest, catching hard and hurting him. He wanted to shout out what he’d seen, bring the second watch running back to confirm it. Back then, sightings of serpents were rare, and many a landsman still claimed they were no more than sea-tales. But he also knew what the sailors said about the big serpents. A man who sees one sees his own death. With sudden certainty, Brashen knew that if anyone else knew he’d seen one, it would be taken as an ill omen for the entire ship. There’d be only one way to purge such bad luck. He’d fall from a yard when someone else didn’t quite hold the flapping canvas down tightly enough, he’d fall down an open hatch and break his neck, or he’d just quietly disappear some night during a long dull watch.

Despite the fact that he’d been toying with the notion of suicide but a moment before, he was suddenly sure he didn’t want to die. Not by his own hand, not by anyone else’s. He wanted to live out this thrice-damned voyage, get back to shore and somehow get his life back. He’d go to his father, he’d grovel and beg as he’d never grovelled and begged before. They’d take him back. Perhaps they wouldn’t take him back as heir to the Trell family fortune, but he didn’t care. Let Cerwin have it, Brashen would be more than satisfied with the portion of a younger son. He’d stop his gambling, he’d stop his drinking, he’d give up cindin. Whatever his father and grandfather demanded, he’d do. He was suddenly gripping life as tightly as his blistered hands gripped the rail, watching the scaled cylinder of flesh slide along effortlessly in the wake of the ship.

Then came what had been worst. What was still worst, in his dreams. The serpent had known its defeat. Somehow, it had sensed he would not fall prey to its guile, and with a shudder as jolting as Farsey’s hand on his crotch, he knew that the impulse had not been his own, but the serpent’s suggestion. With a casual twist, the serpent slid from the cover of the ship’s wake, to expose its full sinuous body to his view. It was half the length of the Spray and gleamed with scintillant colours. It moved without effort, almost as if the ship drew it through the water. Its head was not the flat wedge shape of a land serpent but full and arched, the brow curved like a horse’s, with immense eyes set to either side. Toxic barbels dangled below its jaws.

Then the creature rolled to one side in the water, baring its paler belly scales, to stare up at Brashen with one great eye. That glance was what had enervated him and sent him scrabbling away from the railing and fleeing back to the forepeak. It was still what woke him twitching from his nightmares. Immense as they had been, browless and lashless, there had still been something horribly human in the round blue eye that gazed up at him so mockingly.

Althea longed for a freshwater bath. As she toiled up the companionway to the deck, every muscle in her body ached, and her head pounded from the thick air of the aft hold. At least her task was done. She’d go to her stateroom, wash with a wet towel, change her clothes and perhaps even nap for a bit. And then she’d go to confront Kyle. She’d put it off long enough, and the longer she waited, the more uncomfortable she became. She’d get it over with and then damn well live with whatever it brought down on her.

‘Mistress Althea.’ She had no more than gained the deck before Mild confronted her. ‘Cap’n requires you.’ The ship’s boy grinned at her, half-apologetic, half-relishing being the bearer of such tidings.

‘Very well, Mild,’ she said quietly. Very well, her thoughts echoed to herself. No wash, no clean clothes and no nap before the confrontation. Very well. She took a moment to smooth her hair back from her face and to tuck her blouse back into her trousers. Prior to her task, they had been her cleanest work clothes. Now the coarse cotton of the blouse stuck to her back and neck with her own sweat, while the trousers were smudged with oakum and tar from working in the close quarters of the hold. She knew her face was dirty, too. Well. She hoped Kyle would enjoy his advantage. She stooped as if to refasten her shoe, but instead placed her hand flat on the wood of the deck. For an instant she closed her eyes and let the strength of the Vivacia flow through her palm. ‘Oh, ship,’ she whispered as softly as if she prayed. ‘Help me stand up to him.’ Then she stood, her resolve firm once more.