Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

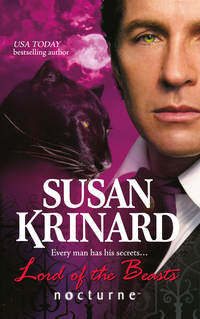

Kitabı oku: «Lord of the Beasts»

Praise for Susan Krinard

and her books

“A poignant tale of redemption”

—Booklist on To Tame a Wolf

“Its compelling characters and the universal nature of their

underlying conflicts should guarantee an across-the-board

appeal to general fantasy fans and other readers.”

—Library Journal on The Forest Lord

“A master of atmosphere and description”

—Library Journal

“Readers … will be pleasantly surprised at the depth and

breadth of this novel. Character-driven, enhanced by plenty

of adventure, it encompasses a far wider scope than a romance.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub on Shield of the Sky

“The standard for today’s fantasy romance.”

—Affaire de Coeur on Shield of the Sky

“Krinard is a bestselling, highly regarded writer who is

deservedly carving out a niche in the romance arena.”

—Library Journal

“Susan Krinard was born to write romance”

—New York Times bestselling author Amanda Quick

Also available from Susan Krinard

HALFWAY TO DAWN

BRIDE OF THE WOLF

LUCK OF THE WOLF

CODE OF THE WOLF

Lord of the Beasts

Susan

Krinard

To the Animals

‘I think I could turn and live with animals, they

are so placid and self-contain’d,

I stand and look at them long and long.’

—Walt Whitman

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Kathy Flake, who hosted my first trip to the

beautiful Cotswolds. She is a true friend to the animals.

CHAPTER ONE

London, 1847

THE WOMAN WAS BEAUTIFUL as no earthly creature could be, flawless in form and carriage, her hair cascading over her shoulders like Fane gold spun by a master weaver. The world of men had names for her kind: Fairy and Daoine Sidhe and Fair Folk among them—but no such description could begin to capture her radiant perfection. Her ivory face shone with a stern radiance that no mortal could gaze upon without recognizing that he was nothing but a low, wretched brute in the presence of divinity.

Donal wasn’t afraid, though Da had left him alone with the Queen of Tir-na-Nog. The man known by humans as Hartley Shaw—the Forest Lord, stag-horned master of the northern forests—had been cast out of the Blessed Land, driven away by his own mother because he would not give up his love for the mortal Eden Fleming. But now Queen Titania gazed down at her grandson and spoke, smothering the little spark of defiance Donal nursed in his six-year-old heart.

“Your father has made his choice,” she said, her voice sweeping over Donal like a blast of cold north wind. “But you are young, and your blood may yet serve your people.”

Donal had heard those same words a hundred times before, and always he gave the same answer. “I want to go home, with Da.”

“Home.” Titania flicked her slender fingers, and silver leaves shook loose from the stately tree beneath which she stood. “The vile sty mortals have made of the good, green earth. That is what you return to, child.”

Though Donal knew there were many bad things in the world, he knew it was not as terrible as his grandmother said. Animals still ran free in the forest beyond the Gate. Ma and Da had seen to that. No matter what happened anywhere else in the land called England, Hartsmere would always be safe.

“But not for you,” Titania said. “Never for you, grandson. You will find no peace at your mother’s hearth. You will always be torn between two worlds, and your father’s choice will haunt you for as long as you live among mortals.” Her lovely face darkened as if a cloud had passed over the ever-shining sun of Tir-na-Nog. “Hear me, and remember. If ever you should love as my son loves … if ever you fall into the snare of a mortal female’s wiles … you will lose the gift that lifts you above the People of Iron. The voices of the beasts will vanish, and you will be alone. You will have nothing … nothing….

DONAL FLEMING WOKE with a start. The voice in his mind faded, and in its place rose the clamor and din of morning at the Covent Garden market.

Only a dream, he thought. Not a memory, real as it seemed … at least not his own. But Tod had been there on that terrible day twenty-five years ago, and the hob had told Donal the story so many times that Titania’s threat had become unquestionable fact.

Donal flung aside the coverlet and swung his legs over the side of the bed. He massaged his temples, seeking in vain to quiet the incessant noise that was inescapable in the vast metropolis called London. With a groan he set his bare feet on the faded carpet and staggered to the washbasin to splash his face with the tepid water that remained from the night before. The few drops that passed his lips tasted of the smoke and coal dust and grime that hung in the London air. He scrubbed his skin with the towel so thoughtfully provided by the hotel staff, but no amount of washing would remove the city’s taint.

He draped the towel over the back of his neck and went to the window overlooking the square below. The competing cries of vendors—sellers of vegetables and fruit, meat pies and bread and sausages, flowers of every variety—mingled with the clatter of cartwheels and hoofbeats, penetrating the thin glass as if it were tissue. Swarming humanity ebbed and flowed between the stalls and shops, kitchen maids bumping elbows with waifs buying violets to sell on street corners and bleary-eyed dandies gulping coffee after a night of theater and tavern.

It was an alien world to Donal. He closed his eyes and thought of the moors with their deep silences and broad, clean skies. At this hour, the farmers would have long since been up milking cows, feeding chickens and mending walls, going about the same business they did every spring morning. And he would be out visiting Eliza’s new litter or helping Mr. Codling and his fellow farmers through the lambing season. He might not utter a word all day, for the taciturn husbandmen of the Dales had little use for idle chatter, and the beasts spoke without need of human language.

With a sigh of resignation, Donal selected an oft-mended shirt and his second-best coat from among the few garments he’d brought from Yorkshire. He was aware that his clothes were sadly out of date, if only because his mother had brought it to his attention on more than one occasion. Lady Eden laughingly despaired of her eldest son, and of his ever finding a wife who could overlook his stubborn refusal to accept his proper station in life.

The station of the bastard child who had been given everything the son of an earl could desire, and cast it all aside. All but his love for his parents and brothers, his memories of Hartsmere and the distant family connections that brought him so far from home.

Donal replaced the towel around his neck with a slightly frayed cravat and worked it into a simple knot at his throat. He glanced in the mirror just long enough to run dampened fingers through the unruly waves of his hair. Surely the August Fellows of the Zoological Society of London had better things to do than critique the appearance of a country veterinarian.

He considered and discarded the notion of a visit to the hotel dining room before setting out for Regent’s Park. He doubted his stomach would tolerate even his usual light breakfast, and he had no desire to see greedy, overfed tourists stuffing their mouths with slabs of beef and rashers of bacon. Instead, Donal unwrapped a hard roll left over from yesterday’s journey and broke it into small bits, wishing he had a friend to share it with.

As if in answer to his thoughts, someone scratched at his sitting room door. The sound came from very near the floor. Donal hurried to the door and opened it, meeting the bright brown eyes of his unexpected visitor.

“Well, now,” he said, squatting to offer his hand. “Have you come to share my bread?”

The parti-colored spaniel cocked his head and gravely regarded Donal’s crumb-dusted fingers. He was no street cur to go begging for his meals; his red and white coat gleamed with the luster of frequent grooming and good health, and he wore his handsome, studded collar as if it were the crown of the Cavalier King who had given his breed its name.

Donal set the roll on the ground and listened. For all his well-bred dignity, the spaniel’s thoughts were clear and honest in the way of his kind, and he gazed at Donal with absolute trust. The dog’s natural intelligence had warned him that something was amiss when his human would not rise from his bed to take him for his morning walk. When his friend only groaned at the patting of a paw and an encouraging lick, he had set aside good manners and barked until another human had come to investigate the uproar. Then he had dashed between the startled woman’s feet and run as fast as his legs would carry him, straight to the one place in all London where he knew he would be understood.

“I see,” Donal said, resting his hand gently on the spaniel’s broad forehead. “Of course I’ll do what I can.” He stuffed the roll in his pocket, rose and followed the dog into the hallway and around two corners to a door indistinguishable from his own. He knocked, but there was no answer. The spaniel whined anxiously.

Donal turned the knob, and the door gave at his push. Immediately his nostrils were assaulted by the smell of sickness. The sitting room was far more luxurious than his own modest suite, with thick Oriental carpets and furnishings that a wealthy nabob might find acceptable.

Donal strode to the bedchamber, took one glance at the rumpled bed’s motionless occupant and gave a sigh of relief. For all the signs of recent illness, the spaniel’s master was neither near death nor in urgent need of a physician’s care.

He dampened a towel at the washstand and sat beside the stout, middle-aged object of the canine’s adoration. The man had the look of prosperity about him, but he had clearly behaved with intemperance and paid the consequences. He mumbled an irritable query under his breath and subsided back into sleep.

“It’s nothing to worry about, Sir Reginald,” Donal said to the dog as he bathed the florid, mottled face and listened to the steady pulse beating in the man’s bejowled throat. “He’s only drunk more than is good for him.”

The spaniel jumped onto the bed and intently studied his master’s face, silky ears lifted.

“What he needs now is rest,” Donal said, rinsing the towel and laying it across the man’s forehead. “He’ll wake when he’s ready.”

Sir Reginald hesitantly wagged his tail. Donal tucked the bed’s coverlet under his master’s chin and clucked his tongue in invitation. After a last glance at his human, Sir Reginald followed Donal from the room.

No one paid any heed to a respectable guest and his dog as they strolled casually from the hotel lobby. Sir Reginald liked the hubbub of the market no better than Donal, so they beat a hasty retreat to the dining room, where Donal ordered steak and water for the dog and plain eggs and toast for himself. A pair of severe business men at a nearby table cast disapproving glares at the spaniel, who crouched patiently between Donal’s boots.

The waiter returned a few minutes later with a harried-looking young man whose high collar points had scratched red welts into his cheeks. The young man scurried about Donal’s table, craning his neck to see under it, and came to a nervous halt just out of arms’ reach.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, jerking his head very high, “but I have had complaints … it is my understanding that you have brought an animal into the dining room.”

Sir Reginald cringed, his naturally ebullient nature suppressed by the uneasy hostility in the young man’s approach. Donal quieted him with a quick pat and got to his feet.

“I have brought a friend to dine with me,” he said quietly, meeting the young man’s eyes. “I’m sure you can see that he is not inconveniencing anyone.”

The fellow looked pointedly toward the businessmen. “Are you a guest at this establishment, sir?”

“I am.”

“Then surely you will agree that it is our duty to see that respectable standards of decency and cleanliness are upheld. If you will kindly provide the direction of your room, I will send a porter to return the beast—”

A low-pitched growl sounded from under the table, and the young man shuffled a few steps back. Donal smiled. “Sir Reginald prefers not to be disturbed,” he said, “but I will personally attest to his good behavior.”

“You refuse to remove the animal?”

In answer, Donal resumed his seat and pretended interest in a neatly mended tear on his coat sleeve. The young man sputtered. “You leave me no choice then, sir.” He signaled to a waiter, who scurried off toward the kitchen doors.

By now the scene of dispute had attracted the attention of the other diners, who shook their heads as they continued to gorge themselves from overflowing plates. A waiter with a thatch of bright red hair sidled up to Donal and leaned close under the pretense of delivering a copy of the morning paper.

“I likes dogs, sir,” he whispered, smoothing the paper as he laid it on Donal’s table. “Thought you should know that they’ve sent for the constable.” He passed a wrapped bundle into Donal’s hand. “This’ll do for the little mite. You’d best make yerself scarce, sir.”

Donal concealed his surprise and accepted the package with a nod. Sir Reginald emerged from beneath the table and politely wagged his tail at the waiter, then set off at a purposeful trot for the door to the street.

Donal casually rose and followed the spaniel, ignoring the critical gazes of the men who awaited the drama’s denouement. He reached the door and opened it, admitting a rush of noise, dust and pungent odors from the market. He closed his eyes and cast his thoughts outward like a net. Here and there, like drifting bits of flotsam in an ocean of humankind, the questing sparks of intelligent animal minds searched for the means to survive another day.

Donal called out an invitation, and they answered. Sir Reginald fidgeted on his haunches and pricked his ears toward the silent tide gathering from every quarter of Covent Garden. The wave was lapping at the very shores of Old Hummums Hotel when the officious young waiter reemerged from the rear entrance with a tail-coated constable.

By then it was too late. Donal scooped Sir Reginald into his arms and stepped out of the doorway just as the first hungry mongrel skittered into the dining room. The head waiter stopped in his tracks, open-mouthed, and one of the businessmen rose to his feet. But the flood could not be stemmed. As the dog on point skirmished toward the nearest table, his company surged in after him, a wash of furry projectiles, large and small, in every imaginable color of dusty white, brown, red, black and yellow. Yapping with the joy of sinners facing the promise of salvation, the dogs leaped upon the feast—the largest hounds planting enormous paws on table tops as they wolfed steaks and loafs of bread with equal fervor, the smallest dashing beneath to collect the fallen scraps. Not one was left wanting.

There were no ladies present in this honorable bachelor establishment to swoon at the terrifying sight of filthy beasts pilfering meals intended for their betters. Most of the men had the sense to get out of the way. One fat gentleman struggled over a roast chicken leg with an equally stubborn mastiff, whose jaws proved more effective than plump fingers accustomed to counting money and lifting nothing heavier than a silver spoon.

In a matter of minutes it was over. The constable was vastly outnumbered, and had better sense than to try to control a score of overexcited canines whose only goal was to fill their empty bellies. No human being was injured in the melee. And when the dogs had cleared every plate and licked up every crumb from the floor, they took Donal’s advice and raced back out the door to scatter and lose themselves again among the two-legged folk who could not be bothered to take an interest in their welfare.

Sir Reginald squirmed with delight and licked Donal’s chin. Donal slipped out the door on the heels of the last stragglers. Someone shouted behind him. He closed the door and strode briskly into the milling crowds of the marketplace, losing himself as thoroughly as the four-legged thieves.

He knew he could find a way back to his rooms without attracting undue attention, and certainly no rational man could suggest that he’d had anything to do with an unprecedented invasion of street curs. Nevertheless, the waiter’s advice to “make himself scarce” seemed very sound at the moment, and once Donal had restored Sir Reginald to his human, he would lose no more time in visiting his mother’s acquaintance in Regent’s Park.

The hallway leading to his rooms was deserted. He went on to Sir Reginald’s lodgings and knocked on the door, hardly expecting a response. But the door opened to the sober face of a tall man in well-cut but modest garments who raised an inquiring brow and kept the door half shut against any intrusion.

“I beg your pardon,” Donal said. “I am seeking the gentleman who has engaged these rooms. I’ve been looking after his dog and wish to return him.”

The tall man glanced at Sir Reginald, comfortably ensconced in Donal’s arms, and shook his head. “I fear that will be impossible, sir,” he said. “Mr. Churchill has but recently passed beyond this mortal coil.”

“He’s dead?” Donal asked, stunned. “I saw him only an hour past, and he …”

“It was very sudden, I believe.” He bowed his head for a moment of respectful silence. “I am Doctor Tomkinson. The maid summoned me when she found Mr. Churchill fallen on the floor.” He frowned into Donal’s face. “You say you saw him alive?”

“He was indisposed, to be sure, but with a strong pulse and no indication of severe illness.”

“His death was due to complications of dropsy, a weakness in the heart. Are you a physician yourself, sir?”

“I am Dr. Fleming, a practitioner of animal medicine.”

“I see. Then you were a friend of the deceased?”

“We were never acquainted. His dog came to me in some distress, sensing his master’s illness.” Donal held the little dog more tightly, knowing the animal had not yet recognized his loss.

“A clever beast,” Tomkinson said without inflection. “Unfortunately, there is no one to care for it here. I understand that Mr. Churchill was a bachelor with no relations who might take the animal. You must have the means to see it humanely destroyed….”

With a wail as wrenching as any child’s cry, Sir Reginald launched himself from Donal’s arms and dashed between Tomkinson’s legs into the room. Donal didn’t hesitate to follow the spaniel to the sheet-draped form on the bed.

Sir Reginald crept onto his master’s motionless chest, rested his head on his paws and whined piteously.

“This is hardly appropriate …” Tomkinson began. Donal turned, silenced the man with a look and knelt beside the bed.

“He is gone,” he said gently. “I failed you, my friend.”

The spaniel made no response. Donal knew Sir Reginald would remain here with the body until he pined away from thirst and starvation, but neither Tomkinson nor the hotel staff would permit such a display of self-sacrifice. They would turn him over to the dog-catchers or put him out on the street to fend for himself.

Donal gathered the limp dog in his arms and tucked Sir Reginald beneath his coat. “Tomorrow we’ll leave London,” he said. “I have one obligation to fulfill, but if you wait for me, I’ll take you to a place that I believe will be to your liking.”

Sir Reginald sighed and closed his eyes. He would not be comforted now, but he was a dog; in time he would accept and find joy again. That was the way of the animals … to live fully in the moment instead of wasting the gift of life in regret, resentment and fear of the future.

It was not so unlike life in Tir-na-Nog.

Donal walked past Tomkinson to the door and paused when the physician cleared his throat.

“You don’t really believe that beast understands you?” Tomkinson asked.

“He understands far more than you can imagine. And he very much fears that if you continue to overindulge in hard drink, you will meet the same fate as Mr. Churchill.”

Tomkinson might have managed some affronted response, but Donal didn’t wait to hear it. He returned to his room, made a nest of blankets and pillows on the floor in a corner tucked behind the bed, and left the steak and a tin of fresh water for Sir Reginald. Once he was satisfied that the spaniel would at least be comfortable in his grief, Donal gave the dog a final pat and collected his bag.

He was almost out the door when a rush of warmth and unrestrained love washed over him like summer sunlight. It was enough to carry him through the grim, unhappy streets of London, and nearly enough to make him glad that he was half-human.