Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

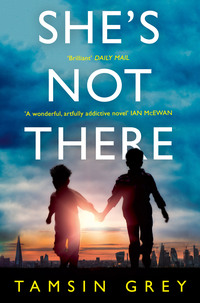

Kitabı oku: «She’s Not There», sayfa 6

17

They found some ice cream in the freezer, and a pizza, which they cooked in the microwave, so it came out more like a Frisbee than a pizza. Jonah tried cutting into it and it splintered into bits. He chopped up the mango instead, which was difficult, and he cut his finger, and the blood mingled with the mango juice on the kitchen table. The mango was completely delicious, but they still felt hungry so they ate the ice cream, which was butterscotch. They ate it straight from the tub, and finished it, and then they felt sick and went and lay on the sofa in the sitting room. The cricket was finished so they watched the Tour de France, but Bradley Wiggins wasn’t in it, and it was hard to work out what was going on.

‘Where is she?’

‘I don’t know.’

Raff sighed. ‘She must be dead.’

‘Don’t say that, Raff. Of course she’s not dead.’

‘Dead, or a bad man’s got her. Otherwise she would of come back by now.’

Jonah felt in his pocket for her phone, and held it, feeling its solidness. ‘The thing is, she might come back at any minute.’

Raff got up and went and opened the front door, and looked left and right. Then he slumped down onto the doorstep. Jonah went and sat next to him. Shadows had started to fall across the road, and it felt quiet and sleepy. The sky was still very blue, and Jonah thought about the gods in Jason and the Argonauts again, looking down, deciding what would happen next. Then Alison, Greta and Mabel appeared, from the direction of the park. Alison was carrying a big bag with a towel trailing out of it, so they’d probably been to the paddling pool. They were all quite pink, and Greta and Mabel were arguing. Alison was telling them not to, but then she noticed the boys and shaded her eyes to look at them. Jonah waved, but Greta hit Mabel, who burst out crying, and Alison was distracted from waving back. They went into their house and the road was quiet again, and Jonah felt a deep sadness steal up on him.

‘Jonah.’ Raff’s voice was thoughtful, and he was sitting very still.

‘What?’

‘Why doesn’t Alison like us?’

‘Because she’s not a very nice person.’

‘Is it because of Angry Saturday?’

Jonah stared at Alison’s dark green shiny door. ‘I think she already didn’t like us. Or didn’t like Lucy.’ He was remembering long ago, the itch of his spots and Raff crying all the time, and Lucy crying too, though she’d tried to hide it. ‘Lucy invited them to tea once.’

‘Really?’ Raff sounded like he didn’t believe it.

‘We both had chicken pox and we couldn’t go out anywhere, and it was really boring, and Daddy said Mabel and Greta had already had chicken pox and to invite them all over.’ Roland was always telling her she should make more of an effort with people.

‘I don’t remember them coming to tea.’

‘You were just a toddler. And anyway, they didn’t.’

‘Why not?’

Jonah stared at the green door. It had been lovely weather and Raff had been crying and crying, and Lucy had seen Alison coming out of the Green Shop with the girls in their buggy, and had put Raff down and run and opened the front door. He closed his eyes, remembering Alison looking down at him, commenting on his spots, and saying they’d got that one over with a few months ago.

‘So you can come in for a coffee!’ Lucy had cried, but they were off to the park to meet up with some friends. ‘Pop in later, then! Come for tea! 5 p.m.!’ And Alison had replied, over her shoulder, that that would be lovely. Lucy had spent all day tidying up and had even managed to make a cake, in between walking Raff up and down.

‘Because of Angry Saturday?’

‘I already told you, Raff, it was before Angry Saturday.’

‘So why didn’t they, then?’

Jonah closed his eyes again. They hadn’t come at 5 p.m., and they’d waited and waited, and then they’d gone to sit on the step to look out for them. And when they did finally appear, with lots of other mums with buggies, and Lucy had stood up, Raff on her hip, waving and smiling, Alison had waved back – but then she’d opened her own front door and all the mums and buggies had gone inside and the door had shut. And Lucy had sat back down, staring, with her sad, tired eyes, at Alison’s dark green door; and Raff had started crying again.

‘Is Alison racist?’

Jonah opened his eyes. Opposite, one of the squatters, the one with the bald head, came out and sat on the doorstep, just like them. The squatter was the opposite of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, he realised, the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò being tiny, with a huge head, and the squatter being big and tall, with a tiny head.

‘Is she?’ Raff nudged him.

‘I don’t know, Raff. Probably not.’

The squatter looked across and nodded at them, and got out his tobacco and rolling papers. It was finally starting to cool down.

‘She’s not coming,’ Raff said.

Jonah watched the squatter light his smoke. The sadness was making his stomach hurt. He looked back at Alison’s front door. Alison doesn’t like you, Lucy. No one likes you. Even Dora doesn’t like you any more. The squatter sucked. Jonah watched the smoke billowing out of his nostrils.

‘Maybe we should phone Daddy,’ said Raff.

‘You can’t just phone people in prison. It’s more complicated than that.’

In the silence, they could just hear Alison’s voice, shouting at Mabel and Greta. The squatter was leaning over his knees, squishing the smoke out on the pavement. Then he stood up and stretched his arms above his head.

Raff stood up too. ‘Slingsmen,’ he said.

18

Jonah was Slygon, and Raff was Baby Nail. Jonah kept winning, but Raff started getting fed up, so he let him win a few. He kept an eye on the clock, and when it got to 9 p.m. he said it was bedtime.

‘That’s not fair, I haven’t won hardly any yet!’ Raff threw his nunchuck down and went and lay on the sofa, face down.

Jonah stared down at Raff’s back. Then he scrunched his eyes tight shut, to pray, or to make a wish, or to try and reach her, somehow. Please come back. He said it over and over in his head, but the only answer was the Slingsmen tune. His stomach lurched at the endless emptiness of everything, and he tried to get a sense of a god, watching him: Ganesha, with his kind little elephant eye, or the Christian god, his bearded face all cloudy. Or maybe a group of gods in their togas? Was what was happening a kind of test? If he did the right thing, would he get her back? And was she up there, with the gods, was she waiting for him to work it out, to pass the test, so that she could return; holding her breath, wanting to shout clues to him?

The Slingsmen tune tinkled on and on, with the occasional phwoof of a released missile. He opened his eyes, dropped his nunchuck, and pulled her phone out of his pocket. The smallness of it, the lightness, the scratched redness, the way it flipped open and closed: so familiar, it was like an actual part of her. He flipped it open and looked at the text from Sunday morning.

Tonight X

He glanced down at Raff, and walked out of the room.

In the kitchen he pressed the green call button and held the phone to his ear. As it rang, he batted away a fly, and looked out at the corduroy cushion in the yard. The phone rang and rang, and then it rang off. No voice telling him to leave a message; just silence.

He snapped the phone closed and laid it on the table. He went out into the yard and checked that the diary hadn’t slid under the cushion. He walked back into the kitchen and looked for it on the windowsills and among the piled-up plates and bowls. Then he squeezed his eyes tightly shut again, trying to see her, to bring up her face. I don’t know what to do. Can’t you send me a message? Or some kind of sign?

Back in the sitting room, he wandered over to Roland’s aquarium. The fish had died long ago, just after he’d gone to prison, and they’d emptied the water, and now the tank was full of random objects: chess pieces, a stripy scarf, a broken kite. No diary though. He looked down the back of the sofa, and then pushed his hands under Raff’s body, feeling for the book. Raff pushed him away, swearing, and he rolled onto his back on the floor. There were flies, about ten of them, hanging out on the ceiling. The shape they made could be a messy J for Jonah. Or maybe an L for Lucy. He stared at the insects, waiting for them to form a different shape, to start spelling out a word.

They didn’t. Raff was crying now. Jonah got up and turned off the TV, and came back and perched next to him.

The sudden knock made them both jump into the air. They raced the few steps to the front door, Jonah arriving first and tugging it open.

‘Where have you …!’ he began, preparing to dive up into her arms, but he fell silent, because it wasn’t her. It was Saviour.

19

The sun was setting now, and Saviour’s face was glowing in the pink, spooky light. He was carrying a small wooden crate, and his fingers were still purple. Normally they were glad to see him, eager to let him in – but they both stood in the doorway, gazing out at him.

‘Hello, Saviour,’ said Raff, finally. Saviour nodded and cleared his throat, but instead of saying something, he offered Jonah the crate. His eyes were strangely pale: caramel instead of the usual brown.

‘Thank you,’ said Jonah, looking down. Plums, not blackcurrants; fat yellow ones, their skins breaking open, showing the squishy flesh. He turned and put the crate down, next to the petrol can.

‘Are you going to let me in?’ Saviour’s voice was very croaky and his breath smelt like Lucy’s nail varnish remover.

‘Lucy’s not here,’ he said quickly. ‘She’s gone to yoga. She’s only just left.’

Saviour looked down Southway Street, as if he might catch a glimpse of her going round the corner.

‘Are you having roast chicken?’ asked Raff.

Saviour shook his head. ‘Not tonight.’ The words were slurred, as well as croaky. He must have been drinking.

‘Is Dora going to die?’

‘Shut up, Raff,’ said Jonah. Saviour’s weird eyes fixed on him. His pupils were two tiny black dots, and it crossed Jonah’s mind that an alien had taken over his body.

‘You can come in if you want,’ said Raff. Jonah nudged him, but Raff elbowed him back and jumped down from the doorstep. ‘You can play Slingsmen with us, until she comes back!’

‘Good plan.’ Saviour took a breath and seemed to become himself again. He stepped forward, putting a hand on Raff’s shoulder, but then stopped. His eyes had closed and his mouth hung open, his bulldog cheeks sagging low. It was like he had fallen asleep. He must be really drunk, which was strange, because he was meant to have given up alcohol forever. Then his phone started ringing, from the pocket on his shirt, and Jonah and Raff both jumped, but Saviour’s eyes stayed shut. Jonah and Raff looked at each other as it kept on ringing.

‘You should answer it,’ said Raff, shrugging the hand off his shoulder and giving him a little push. Saviour’s eyes opened, and he nodded and felt for his phone. Once he had it in his hand, he stared at the flashing screen.

‘Answer it, then!’ said Raff.

Saviour nodded again and held the phone to his ear.

‘Dad?’ Emerald’s voice was small and tinny, but clear.

‘Yes, love.’

Emerald’s voice began to wail, and Saviour flinched, suddenly wide awake. He cleared his throat. ‘OK, love. Don’t worry. I’m on my way.’ She kept wailing, but he cut her off. Slipping the phone back into his pocket, his alien eyes came to rest on Jonah again.

‘Saviour.’ It was Alison. She had probably been watching them from her front window. Saviour’s face stretched into a peculiar grin, but then he covered his mouth with his hand, as if he’d realised about his breath.

‘Alison. How are you?’ he said, through his fingers.

‘Fine.’ She said it emphatically, folding her arms tightly. She looked at the boys. ‘How’s your mum? Isn’t it time you were in bed?’

Jonah nodded.

‘Good. Saviour, I was wondering if I could have a word?’

‘It’s actually not the greatest time, Ali—’ He pulled out his keys and looked over at his van, which was parked outside the Green Shop.

‘It won’t take a minute.’ Alison took Saviour’s arm. ‘Goodnight, boys!’

Back in the sitting room, they watched Alison and Saviour reaching the van, Alison talking and talking as Saviour put the key in the driver door. He looked over at them, and Alison looked too, so they ducked down and lay on the floor.

‘Can she tell that he’s drunk, do you think?’ Jonah whispered.

‘Is that what’s up with him!’ Raff got to his knees, and risked another peek. ‘She’s too busy cussing Mayo,’ he said, lying back down. They listened to Saviour’s van drive away, and Alison’s shoes clipping back to her house. Then there was just the tinkly Slingsmen tune again. Jonah gazed at Roland’s aquarium, remembering the bright, flitting fish. Four parrotfish, three angelfish and eight swordtails. The fish food had run out, so they’d fed them cornflakes, and they’d all died.

Raff sat up. ‘Who’s going to read us a story?’ His voice was very small.

‘I’ll read a story,’ said Jonah. ‘What story would you like, Raffy boy?’

20

It was very hot upstairs. They went into the bathroom and Jonah stood on the lid of the toilet and pushed the window wide open. The sky was all streaky, and the birds were singing – sweet little chirps in the dusk. A couple of flies had drowned in Lucy’s bathwater, and neither of them wanted to put their hands in and pull out the plug. They brushed their teeth and took off their clothes, and Jonah bundled them all into the laundry basket, but then he took them out again, remembering that there were no clean ones. Raff got a book out of their bedroom, and they went into Lucy’s room with it, because that’s where she read to them sometimes, sitting up in her bed with a boy either side. They got in and pulled the sheet up over their naked bodies. Her smell was coming from the tiny particles of her left behind on the cotton, and in the air. Was that what a ghost was, millions of molecules, hanging together in an invisible swirl? He opened the book. It was one that they’d got out of the library ages ago, but never got round to reading, a proper chapter book, and the words looked very small and close together. Trying to get rid of the idea that Lucy was dead, he focused on the first sentence.

‘“Until he was four years old James Henry Trotter had a happy life,”’ he read. But sadness and worry gripped his stomach, and he let the book drop into his lap. Through the window, above the Broken House, he saw that the sky was finally darkening, and as he watched a single star came out.

‘Why have you stopped?’ Raff sat up and peered at Jonah’s face. Jonah looked down at the book. Then he shut it and got up and went over to Lucy’s chest of drawers.

Some of her underwear was spilling out of an open drawer, and he pushed it all back in and pushed the drawer shut. He climbed up, wedging his toes onto the wooden handles, and reached for the wire tray that lived on top of the chest. It was piled high, with letters and other bits of paper, and when he jumped back down with it, most of the papers slid out and fluttered to the floor.

‘What are you looking for?’

‘Her diary.’ It wasn’t there. He sat down and gathered up the fallen papers, which were mainly printed, and to do with money: lots from Jobcentre Plus, a couple from Smart Energy, a few from something called HSBC. As he gathered them up again, he noticed a postcard from the dentist saying they should come for a check-up, a letter about a clinic appointment, and one about their overdue library books, which made him shake his head. A white, handwritten envelope stood out from all the printed pages, and he stopped piling up the papers to look at it. Their address, of course, in handwriting he recognised; and there was a prison stamp on the back.

‘What are you doing?’ Raff sounded like he might start crying again. Jonah pulled the two sheets of letter paper out of the envelope.

Hello there, Lucy

Firstly, I want you to know that I don’t blame you for refusing to testify. I don’t really blame you for anything.

Raff had come to stand next to him. Jonah looked at his brother’s feet, which were big and long-toed, like Lucy’s, and then at the date at the top of the page. The letter was from 2011, the year Roland had got sent to prison. Ages ago. He stood up. ‘I think we should go into our own room,’ he said.

It was a tiny bit cooler in their room, and not as smelly. They could hear Leonie murmuring to someone, in between big drags on her smoke, and the other person grunting now and then. Raff got into his bed and Jonah sat on the floor, the carpet rough on his bare bottom. Raff said, ‘Read the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò.’

Some of the words in the poem were hard, but he knew it more or less off by heart. He tried to read it like Lucy did, in the same soft, chanting voice.

On the Coast of Coromandel

Where the early pumpkins blow,

In the middle of the woods

Lived the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò.

As he read, he remembered again the feeling from the evening before, listening to Lucy’s voice: his own mother, unknown, unreachable.

Two old chairs, and half a candle, –

One old jug without a handle, –

These were all his worldly goods:

In the middle of the woods,

These were all the worldly goods,

Of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò.

Such a sad story. Such a strange, lonely man, who loves the Lady Jingly Jones, who is also lonely, with only her hens to talk to. But when he asks her to be his wife, and to share his worldly goods with her, she cries and cries, and twirls her fingers, and says no.

‘Mr Jones – (his name is Handel, –

Handel Jones, Esquire, & Co.)

Dorking fowls delights to send,

Mr Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò!

Keep, oh! keep your chairs and candle,

And your jug without a handle, –

I can merely be your friend!

– Should my Jones more Dorkings send,

I will give you three, my friend!

Mr Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò!’

Raff sighed and rolled over. Jonah paused, staring at the picture: the Lady Jingly Jones, with her huge, feathered hat, weeping. Why had Handel Jones left her there on that heap of stones? And why did he send her hens? And would it really be so wrong of her to get together with Yonghy? Then he wondered if Handel might be in prison, like Roland, and Angry Saturday started flashing in his head. The sexing on the table, and then the peacock, with its terrible cry, and Bad Granny’s hand, reaching for him, like a claw. Although the way Raff was breathing meant he was already asleep, Jonah started reading again.

‘Down the slippery slopes of Myrtle,

Where the early pumpkins blow,

To the calm and silent sea

Fled the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò

There beyond the Bay of Gurtle,

Lay a large and lively Turtle, –

You’re the Cove,’ he said, ‘for me;

On your back beyond the sea,

Turtle, you shall carry me!’

Said the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò,

Said the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò.’

There were another two verses, but it had got too dark to read them. Jonah sat still, feeling himself to be very small. Were the gods all talking about him, deciding whether to help him? Or had they forgotten about him? Had something more interesting come up? He closed the book and ran his finger over the title on the front cover. The black letters had been stamped into the red cardboardy stuff, so you could feel them.

THE JUMBLIES & OTHER

NONSENSE VERSES

The book had been Lucy’s mother’s book, and it was on its last legs. Lucy had Sellotaped its spine, to keep it going a bit longer. There had been a raggedy paper jacket, but it had fallen to bits. He opened it at the first page, where Lucy’s mother had written her name, very neatly. Rose Marjorie Arden. Arden, because she’d written it when she was a child, long before she’d married Lucy’s father and become Rose Marjorie Mwembe. Underneath, in much bigger, messier writing, was Lucy’s name: Lucy Nsansa Mwembe. She was still Lucy Mwembe, even though she was married to Roland. These days women who got married didn’t always change their names to their husband’s. Nsansa had a meaning; she’d told him, but he couldn’t remember what it was.

He let the book slip from his lap, tipped to one side and curled into a little ball on the floor. They hadn’t sung the song, he realised, the song she sang to them every bedtime; a kind of prayer, thanking God for the day, and asking him to look after them through the night. Glory to thee, my God this night … He sang the words in his head, picturing that old, Christian God, with his big white beard, all fatherly and silent, waiting to be noticed. Then he stopped, thinking instead about Rose. She had died a long time ago, when Lucy was a child. Lucy couldn’t remember her that well, but she remembered the bedtime song, which was an English song; and that she’d called her Mayo, a Zambian word for Mummy. She had a tiny photograph of her face in the locket she wore on her throat, showing that she’d been white, with a very straight fringe of dark hair. Their other grandmother. Was she up there with the old, fatherly God, and the angels, with their white, seagull wings? Or had she been reborn? What would she have come back as? He tried to get a sense of her, of her smile, her motherliness, but all he could get was that tiny, faded face in the locket.

It was completely dark now. He curled tighter. They’d never met Lucy’s father either, or her three half-brothers, who all still lived in Zambia. Lucy had run away from them, to England, when she was a teenager. Jonah pictured them, his black Zambian grandfather and uncles, sitting at a table, drinking beer and eating monkey nuts, under a purple-flowered tree; a jacaranda. ‘Whatever happened to Lucy, by the way?’ said one of the uncles, and the grandfather broke open a papery monkey-nut pod, trying to remember.

Leonie was still murmuring away in the street below, and the Kebab Shop Man, because that’s who it was with her, he was joining in more, in his strange high voice, but Jonah couldn’t hear what either of them was actually saying. Every now and then there’d be a pause and the sound of a match striking, and a sharp inhalation. He drifted into a light sleep, and dreamed it was Lucy in the street, smoking and talking to the Raggedy Man. He went to the window and looked down at them, and a spotlight was shining a silver-white light down into the street, from the top of a very high crane. Was it a crane, or was it some kind of weapon? Lucy had her back to him, and Jonah called to her, but she didn’t hear him. The Raggedy Man did, though, he looked right back at Jonah, and his eyes gleamed like silver coins.

When he woke up, it was much cooler, and the silvery light from his dream was in the room. Surprised to be on the floor, and awed by the light, he rolled onto his back. The light bathed his naked body and shimmered on the ceiling. Then he sprang up and went to the window. The street was empty, but above the gleaming roofs hung an enormous moon. It was actually sunlight, Jonah thought, just a shaft of it, from the other side of the world, bouncing off that ball of stone; but it was hard to believe, because the moon looked so alive, a mysterious sky being, and its light had a tenderness to it, like a caress. As he stared, he noticed the moon’s little wise eye, like the eye in his Ganesha painting. And her voice came. She was singing to him, the bedtime song, in her softest, sweetest voice, and he turned and climbed up into his bed and closed his eyes, so that he could fall asleep before it stopped.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.