Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Leftovers»

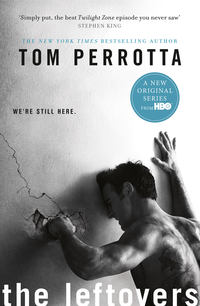

The Leftovers

Tom Perrotta

Copyright

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

First published in Australia in 2011 by HarperCollinsPublishers

Originally published in the United States in 2011 by St. Martin’s Press

THE LEFTOVERS. Copyright © Tom Perrotta 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Cover Art © 2014 Home Box Office, Inc. All Rights Reserved. HBO® is a service mark of Home Box Office, Inc.

The right of Tom Perrotta to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9780007453092

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007453108

Version: 2014-06-30

Dedication

For Nina and Luke

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

Three-Year Anniversary

Heroes’ Day

A Whole Class of Jills

Special Someone

Part Two

Mapleton Means Fun

The Carpe Diem

Blue Ribbon

Vow of Silence

Get a Room

Part Three

Happy Holidays

Dirtbags

Snowflakes and Candy Canes

The Best Chair in the World

The Balzer Method

Part Four

Be My Valentine

A Better-Than-Average Girlfriend

The Outpost

Barefoot and Pregnant

At the Grapefruit

Part Five

Miracle Child

Any Minute Now

So Much to Let Go of

I’m Glad You’re Here

Acknowledgments

Other Books by Tom Perrotta

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

LAURIE GARVEY HADN’T BEEN RAISED to believe in the Rapture. She hadn’t been raised to believe in much of anything, except the foolishness of belief itself.

We’re agnostics, she used to tell her kids, back when they were little and needed a way to define themselves to their Catholic and Jewish and Unitarian friends. We don’t know if there’s a God, and nobody else does, either. They might say they do, but they really don’t.

The first time she’d heard about the Rapture, she was a freshman in college, taking a class called Intro to World Religions. The phenomenon the professor described seemed like a joke to her, hordes of Christians floating out of their clothes, rising up through the roofs of their houses and cars to meet Jesus in the sky, everyone else standing around with their mouths hanging open, wondering where all the good people had gone. The theology remained murky to her, even after she read the section on “Premillennial Dispensationalism” in her textbook, all that mumbo jumbo about Armageddon and the Antichrist and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. It felt like religious kitsch, as tacky as a black velvet painting, the kind of fantasy that appealed to people who ate too much fried food, spanked their kids, and had no problem with the theory that their loving God invented AIDS to punish the gays. Every once in a while, in the years that followed, she’d spot someone reading one of the Left Behind books in an airport or on a train, and feel a twinge of pity, and even a little bit of tenderness, for the poor sucker who had nothing better to read, and nothing else to do, except sit around dreaming about the end of the world.

And then it happened. The biblical prophecy came true, or at least partly true. People disappeared, millions of them at the same time, all over the world. This wasn’t some ancient rumor—a dead man coming back to life during the Roman Empire—or a dusty homegrown legend, Joseph Smith unearthing golden tablets in upstate New York, conversing with an angel. This was real. The Rapture happened in her own hometown, to her best friend’s daughter, among others, while Laurie herself was in the house. God’s intrusion into her life couldn’t have been any clearer if He’d addressed her from a burning azalea.

At least you would have thought so. And yet she managed to deny the obvious for weeks and months afterward, clinging to her doubts like a life preserver, desperately echoing the scientists and pundits and politicians who insisted that the cause of what they called the “Sudden Departure” remained unknown, and cautioned the public to avoid jumping to conclusions until the release of the official report by the nonpartisan government panel that was investigating the matter.

“Something tragic occurred,” the experts repeated over and over. “It was a Rapture-like phenomenon, but it doesn’t appear to have been the Rapture.”

Interestingly, some of the loudest voices making this argument belonged to Christians themselves, who couldn’t help noticing that many of the people who’d disappeared on October 14th—Hindus and Buddhists and Muslims and Jews and atheists and animists and homosexuals and Eskimos and Mormons and Zoroastrians, whatever the heck they were—hadn’t accepted Jesus Christ as their personal savior. As far as anyone could tell, it was a random harvest, and the one thing the Rapture couldn’t be was random. The whole point was to separate the wheat from the chaff, to reward the true believers and put the rest of the world on notice. An indiscriminate Rapture was no Rapture at all.

So it was easy enough to be confused, to throw up your hands and claim that you just didn’t know what was going on. But Laurie knew. Deep in her heart, as soon as it happened, she knew. She’d been left behind. They all had. It didn’t matter that God hadn’t factored religion into His decision-making—if anything, that just made it worse, more of a personal rejection. And yet she chose to ignore this knowledge, to banish it to some murky recess of her mind—the basement storage area for things you couldn’t bear to think about—the same place you hid the knowledge that you were going to die, so you could live your life without being depressed every minute of every day.

Besides, it was a busy time, those first few months after the Rapture, with school canceled in Mapleton, her daughter home all day, and her son back from college. There was shopping and laundry to do, just like before, meals to cook, and dishes to wash. There were memorial services to attend as well, slide shows to compile, tears to wipe away, so many exhausting conversations. She spent a lot of time with poor Rosalie Sussman, visiting her almost every morning, trying to help her through her unfathomable grief. Sometimes they talked about her departed daughter, Jen—what a sweet girl she was, always smiling, etc.—but mostly they just sat together without speaking. The silence felt deep and right, as if there was nothing either of them could say that could possibly be important enough to break it.

YOU STARTED seeing them around town the following autumn, people in white clothing, traveling in same-sex pairs, always smoking. Laurie recognized a few of them—Barbara Santangelo, whose son was in her daughter’s class; Marty Powers, who used to play softball with her husband, and whose wife had been taken in the Rapture, or whatever it was. Mostly they ignored you, but sometimes they followed you around as if they were private detectives hired to keep track of your movements. If you said hello, they just gave you a blank look, but if you asked a more substantive question, they handed over a business card printed on one side with the following message:

WE ARE MEMBERS OF THE GUILTY REMNANT. WE HAVE

TAKEN A VOW OF SILENCE. WE STAND BEFORE YOU AS

LIVING REMINDERS OF GOD’S AWESOME POWER.

HIS JUDGMENT IS UPON US.

In smaller type, on the other side of the card, was a Web address you could consult for more information: www.guiltyremnant.com.

That was a weird fall. A full year had passed since the catastrophe; the survivors had absorbed the blow and found, to their amazement, that they were still standing, though some were a bit more wobbly than others. In a tentative, fragile way, things were starting to return to normal. The schools had reopened and most people had gone back to work. Kids played soccer in the park on weekends; there were even a handful of trick-or-treaters on Halloween. You could feel the old habits returning, life assuming its former shape.

But Laurie couldn’t get with the program. Besides caring for Rosalie, she was worried sick about her own kids. Tom had gone back to college for the spring semester, but he’d fallen under the influence of a sketchy self-appointed “healing prophet” named Holy Wayne, failed all his classes, and refused to come home. He’d phoned a couple of times over the summer to let her know he was okay, but he wouldn’t say where he was or what he was doing. Jill was struggling with depression and post-traumatic stress—of course she was, Jen Sussman had been her best friend since preschool—but she refused to talk to Laurie about it or to see a therapist. Meanwhile, her husband seemed bizarrely upbeat, all good news all the time. Business was booming, the weather was fine, he just ran six miles in under an hour, if you could believe that.

“What about you?” Kevin would ask, not the least bit self-conscious in his spandex pants, his face glowing with good health and a thin layer of perspiration. “What’d you do all day?”

“Me? I helped Rosalie with her scrapbook.”

He made a face, disapproval mingled with forbearance.

“She’s still doing that?”

“She doesn’t want to finish. Today we did a little history of Jen’s swimming career. You could watch her grow up year by year, her body changing inside that blue bathing suit. Just heartbreaking.”

“Huh.” Kevin filled his glass with ice water from the built-in dispenser on the fridge. She could tell he wasn’t listening, knew that he’d lost interest in the subject of Jen Sussman months ago. “What’s for dinner?”

LAURIE COULDN’T say that she was shocked when Rosalie announced that she was joining the Guilty Remnant. Rosalie had been fascinated by the people in white since the first time she saw them, frequently wondering out loud how hard it would be to keep a vow of silence, especially if you happened to bump into an old friend, someone you hadn’t seen in a long time.

“They’d have to give you some leeway in a case like that, don’t you think?”

“I don’t know,” Laurie said. “I kind of doubt it. They’re fanatics. They don’t like to make exceptions.”

“Not even if it was your own brother, and you hadn’t seen him for twenty years? You wouldn’t even be able to say hi?”

“Don’t ask me. Ask them.”

“How can I ask them? They’re not allowed to talk.”

“I don’t know. Check the website.”

Rosalie checked the website a lot that winter. She developed a close I.M. friendship—evidently, the vow of silence didn’t extend to electronic communications—with the Director of Public Outreach, a nice woman who answered all her questions and walked her through her doubts and reservations.

“Her name’s Connie. She used to be a dermatologist.”

“Really?”

“She sold her practice and donated the proceeds to the organization. That’s what a lot of people do. It’s not cheap to keep an operation like that afloat.”

Laurie had read an article about the Guilty Remnant in the local paper, so she knew that there were at least sixty people living in their “compound” on Ginkgo Street, an eight-house subdivision that had been deeded to the organization by the developer, a wealthy man named Troy Vincent, who was now living there as an ordinary member, with no special privileges.

“What about you?” Laurie asked. “You gonna sell the house?”

“Not right away. There’s a six-month trial period. I don’t have to make any decisions until then.”

“That’s smart.”

Rosalie shook her head, as if amazed by her own boldness. Laurie could see how excited she was now that she’d made the decision to change her life.

“It’s gonna be weird, wearing white clothes all the time. I kind of wish it was blue or gray or something. I don’t look good in white.”

“I just can’t believe you’re gonna start smoking.”

“Ugh.” Rosalie grimaced. She was one of those hard-line nonsmokers, the kind of person who waved her hand frantically in front of her face whenever she got within twenty feet of a lit cigarette. “That’s gonna take some getting used to. But it’s like a sacrament, you know? You have to do it. You don’t have a choice.”

“Your poor lungs.”

“We’re not gonna live long enough to get cancer. The Bible says there’s just seven years of Tribulation after the Rapture.”

“But it wasn’t the Rapture,” Laurie said, as much to herself as to her friend. “Not really.”

“You should come with me.” Rosalie’s voice was soft and serious. “Maybe we could be roommates or something.”

“I can’t,” Laurie told her. “I can’t leave my family.”

Family: She felt bad even saying the word out loud. Rosalie had no family to speak of. She’d been divorced for years and Jen was her only child. She had a mother and stepfather in Michigan, and a sister in Minneapolis, but she didn’t talk to them much.

“That’s what I figured.” Rosalie gave a small shrug of resignation. “Just thought I’d give it a try.”

A WEEK LATER, Laurie drove Rosalie to Ginkgo Street. It was a beautiful day, full of sunshine and birdsong. The houses looked imposing—sprawling three-story colonials with half-acre lots that probably would have sold for a million dollars or more when they were built.

“Wow,” she said. “Pretty swanky.”

“I know.” Rosalie smiled nervously. She was dressed in white and carrying a small suitcase containing mostly underwear and toiletries, plus the scrapbooks she’d spent so much time on. “I can’t believe I’m doing this.”

“If you don’t like it, just give me a call. I’ll come get you.”

“I think I’ll be okay.”

They walked up the steps of a white house with the word HEADQUARTERS painted over the front door. Laurie wasn’t allowed to enter the building, so she hugged her friend goodbye on the stoop, and then watched as Rosalie was led inside by a woman with a pale, kindly face who may or may not have been Connie, the former dermatologist.

Almost a year passed before Laurie returned to Ginkgo Street. It was another spring day, a little cooler, not quite as sunny. This time she was the one dressed in white, carrying a small suitcase. It wasn’t very heavy, just underwear, a toothbrush, and an album containing carefully chosen photographs of her family, a short visual history of the people she loved and was leaving behind.

Part One

HEROES’ DAY

IT WAS A GOOD DAY for a parade, sunny and unseasonably warm, the sky a Sunday school cartoon of heaven. Not too long ago, people would have felt the need to make a nervous crack about weather like this—Hey, they’d say, maybe this global warming isn’t such a bad thing after all!—but these days no one bothered much about the hole in the ozone layer or the pathos of a world without polar bears. It seemed almost funny in retrospect, all that energy wasted fretting about something so remote and uncertain, an ecological disaster that might or might not come to pass somewhere way off in the distant future, long after you and your children and your children’s children had lived out your allotted time on earth and gone to wherever it was you went when it was all over.

Despite the anxiety that had dogged him all morning, Mayor Kevin Garvey found himself gripped by an unexpected mood of nostalgia as he walked down Washington Boulevard toward the high school parking lot, where the marchers had been told to assemble. It was half an hour before showtime, the floats lined up and ready to roll, the marching band girding itself for battle, peppering the air with a discordant overture of bleats and toots and halfhearted drumrolls. Kevin had been born and raised in Mapleton, and he couldn’t help thinking about Fourth of July parades back when everything still made sense, half the town lined up along Main Street while the other half—Little Leaguers, scouts of both genders, gimpy Veterans of Foreign Wars trailed by the Ladies Auxiliary—strode down the middle of the road, waving to the spectators as if surprised to see them there, as if this were some kind of kooky coincidence rather than a national holiday. In Kevin’s memory, at least, it all seemed impossibly loud and hectic and innocent—fire trucks, tubas, Irish step dancers, baton twirlers in sequined costumes, one year even a squadron of fez-bedecked Shriners scooting around in those hilarious midget cars. Afterward there were softball games and cookouts, a sequence of comforting rituals culminating in the big fireworks display over Fielding Lake, hundreds of rapt faces turned skyward, oohing and wowing at the sizzling pinwheels and slow-blooming starbursts that lit up the darkness, reminding everyone of who they were and where they belonged and why it was all good.

Today’s event—the first annual Departed Heroes’ Day of Remembrance and Reflection, to be precise—wasn’t going to be anything like that. Kevin could sense the somber mood as soon as he arrived at the high school, the invisible haze of stale grief and chronic bewilderment thickening the air, causing people to talk more softly and move more tentatively than they normally would at a big outdoor gathering. On the other hand, he was both surprised and gratified by the turnout, given the cool reception the parade had received when it was first proposed. Some critics thought the timing was wrong (“Too soon!” they’d insisted), while others suggested that a secular commemoration of October 14th was wrongheaded and possibly blasphemous. These objections had faded over time, either because the organizers had done a good job winning over the skeptics, or because people just generally liked a parade, regardless of the occasion. In any case, so many Mapletonians had volunteered to march that Kevin wondered if there’d be anyone left to cheer them on from the sidelines as they made their way down Main Street to Greenway Park.

He hesitated for a moment just inside the line of police barricades, marshaling his strength for what he knew would be a long and difficult day. Everywhere he looked he saw broken people and fresh reminders of suffering. He waved to Martha Reeder, the once-chatty lady who worked the stamp window at the Post Office; she smiled sadly, turning to give him a better look at the homemade sign she was holding. It featured a poster-sized photograph of her three-year-old granddaughter, a serious child with curly hair and slightly crooked eyeglasses. ASHLEY, it said, MY LITTLE ANGEL. Standing beside her was Stan Wash-burn—a retired cop and former Pop Warner coach of Kevin’s—a squat, no-neck guy whose T-shirt, stretched tight over an impressive beer gut, invited anyone who cared to ASK ME ABOUT MY BROTHER. Kevin felt a sudden powerful urge to flee, to run home and spend the afternoon lifting weights or raking leaves—anything solitary and mindless would do—but it passed quickly, like a hiccup or a shameful sexual fantasy.

Expelling a soft dutiful sigh, he waded into the crowd, shaking hands and calling out names, doing his best impersonation of a small-town politician. An ex–Mapleton High football star and prominent local businessman—he’d inherited and expanded his family’s chain of supermarket-sized liquor stores, tripling the revenue during his fifteen-year tenure—Kevin was a popular and highly visible figure around town, but the idea of running for office had never crossed his mind. Then, just last year, out of the blue, he was presented with a petition signed by two hundred fellow citizens, many of whom he knew well: “We, the undersigned, are desperate for leadership in these dark times. Will you help us take back our town?” Touched by this appeal and feeling a bit lost himself—he’d sold the business for a small fortune a few months earlier, and still hadn’t figured out what to do next—he accepted the mayoral nomination of a newly formed political entity called the Hopeful Party.

Kevin won the election in a landslide, unseating Rick Malvern, the three-term incumbent who’d lost the confidence of the voters after attempting to burn down his own house in an act of what he called “ritual purification.” It didn’t work—the fire department insisted on extinguishing the blaze over his bitter objections—and these days Rick was living in a tent in his front yard, the charred remains of his five-bedroom Victorian hulking in the background. Every now and then, when Kevin went running in the early morning, he would happen upon his former rival just as he was emerging from the tent—one time bare-chested and clad only in striped boxers—and the two men would exchange an awkward greeting on the otherwise silent street, a Yo or a Hey or a What’s up?, just to show there were no hard feelings.

As much as he disliked the flesh-pressing, backslapping aspect of his new job, Kevin felt an obligation to make himself accessible to his constituents, even the cranks and malcontents who inevitably came out of the woodwork at public events. The first to accost him in the parking lot was Ralph Sorrento, a surly plumber from Sycamore Road, who bulled his way through a cluster of sad-looking women in identical pink T-shirts and planted himself directly in Kevin’s path.

“Mr. Mayor,” he drawled, smirking as though there were something inherently ridiculous about the title. “I was hoping I’d run into you. You never answer my e-mails.”

“Morning, Ralph.”

Sorrento folded his arms across his chest and studied Kevin with an unsettling combination of amusement and disdain. He was a big, thick-bodied man with a buzz cut and a bristly goatee, dressed in grease-stained cargo pants and a thermal-lined hoodie. Even at this hour—it was not yet eleven—Kevin could smell beer on his breath and see that he was looking for trouble.

“Just so we’re clear,” Sorrento announced in an unnaturally loud voice. “I’m not paying that fucking money.”

The money in question was a hundred-dollar fine he’d been assessed for shooting at a pack of stray dogs that had wandered into his yard. A beagle had been killed on the spot, but a shepherd-lab mix had hobbled away with a bullet in its hind leg, dripping a three-block trail of blood before collapsing on the sidewalk not far from the Little Sprouts Academy on Oak Street. Normally the police didn’t get too exercised about a shot dog—it happened with depressing regularity—but a handful of the Sprouts had witnessed the animal’s agony, and the complaints of their parents and guardians had led to Sorrento’s prosecution.

“Watch your language,” Kevin warned him, uncomfortably aware of the heads turning in their direction.

Sorrento jabbed an index finger into Kevin’s rib cage. “I’m sick of those mutts crapping on my lawn.”

“Nobody likes the dogs,” Kevin conceded. “But next time call Animal Control, okay?”

“Animal Control.” Sorrento repeated the words with a contemptuous chuckle. Again he jabbed at Kevin’s sternum, fingertip digging into bone. “They don’t do shit.”

“They’re understaffed.” Kevin forced a polite smile. “They’re doing the best they can in a bad situation. We all are. I’m sure you understand that.”

As if to indicate that he did understand, Sorrento eased the pressure on Kevin’s breastbone. He leaned in close, his breath sour, his voice low and intimate.

“Do me a favor, okay? You tell the cops if they want my money, they’re gonna have to come and get it. Tell ’em I’ll be waiting for ’em with my sawed-off shotgun.”

He grinned, trying to look like a badass, but Kevin could see the pain in his eyes, the glassy, pleading look behind the bluster. If he remembered correctly, Sorrento had lost a daughter, a chubby girl, maybe nine or ten. Tiffany or Britney, a name like that.

“I’ll pass it along.” Kevin patted him gently on the shoulder. “Now, why don’t you go home and get some rest.”

Sorrento slapped at Kevin’s hand.

“Don’t fucking touch me.”

“Sorry.”

“Just tell ’em what I told you, okay?”

Kevin promised he would, then hurried off, trying to ignore the lump of dread that had suddenly materialized in his gut. Unlike some of the neighboring towns, Mapleton had never experienced a suicide by cop, but Kevin sensed that Ralph Sorrento was at least fantasizing about the idea. His plan didn’t seem especially inspired—the cops had bigger things to worry about than an unpaid fine for animal cruelty—but there were all sorts of ways to provoke a confrontation if you really had your heart set on it. He’d have to tell the chief, make sure the patrol officers knew what they were dealing with.

Distracted by these thoughts, Kevin didn’t realize he was heading straight for the Reverend Matt Jamison, formerly of the Zion Bible Church, until it was too late to make an evasive maneuver. All he could do was raise both hands in a futile attempt to fend off the gossip rag the Reverend was thrusting in his face.

“Take it,” the Reverend said. “There’s stuff in here that’ll knock your socks off.”

Seeing no graceful way out, Kevin reluctantly took possession of a newsletter that went by the emphatic but unwieldy title “OCTOBER 14TH WAS NOT THE RAPTURE!!!” The front page featured a photograph of Dr. Hillary Edgers, a beloved pediatrician who’d disappeared three years earlier, along with eighty-seven other local residents and untold millions of people throughout the world. DOCTOR’S BISEXUAL COLLEGE YEARS EXPOSED! the headline proclaimed. A boxed quote in the article below read, “‘We totally thought she was gay,’ former roommate reveals.”

Kevin had known and admired Dr. Edgers, whose twin sons were the same age as his daughter. She’d volunteered two evenings a week at a free clinic for poor kids in the city, and gave lectures to the PTA on subjects like “The Long-Term Effects of Concussions in Young Athletes” and “How to Recognize an Eating Disorder.” People buttonholed her all the time at the soccer field and the supermarket, fishing for free medical advice, but she never seemed resentful about it, or even mildly impatient.

“Jesus, Matt. Is this necessary?”

Reverend Jamison seemed mystified by the question. He was a trim, sandy-haired man of about forty, but his face had gone slack and pouchy in the past couple of years, as if he were aging on an accelerated schedule.

“These people weren’t heroes. We have to stop treating them like they were. I mean, this whole parade—”

“The woman had kids. They don’t need to be reading about who she slept with in college.”

“But it’s the truth. We can’t hide from the truth.”

Kevin knew it was useless to argue. By all accounts, Matt Jamison used to be a decent guy, but he’d lost his bearings. Like a lot of devout Christians, he’d been deeply traumatized by the Sudden Departure, tormented by the fear that Judgment Day had come and gone, and he’d been found lacking. While some people in his position had responded with redoubled piety, the Reverend had moved in the opposite direction, taking up the cause of Rapture Denial with a vengeance, dedicating his life to proving that the people who’d slipped their earthly chains on October 14th were neither good Christians nor even especially virtuous individuals. In the process, he’d become a dogged investigative journalist and a complete pain in the ass.

“All right,” Kevin muttered, folding the newsletter and jamming it into his back pocket. “I’ll give it a look.”

THEY STARTED moving at a few minutes after eleven. A police motorcade led the way, followed by a small armada of floats representing a variety of civic and commercial organizations, mostly old standbys like the Greater Mapleton Chamber of Commerce, the local chapter of D.A.R.E., and the Senior Citizens’ Club. A couple featured live demonstrations: Students from the Alice Herlihy Institute of Dance performed a cautious jitterbug on a makeshift stage while a chorus line of karate kids from the Devlin Brothers School of Martial Arts threw flurries of punches and kicks at the air, grunting in ferocious unison. To a casual observer it would have all seemed familiar, not much different from any other parade that had crawled through town in the last fifty years. Only the final vehicle in the sequence would have given pause, a flatbed truck draped in black bunting, not a soul on board, its emptiness stark and self-explanatory.

As mayor, Kevin got to ride in one of two honorary convertibles that trailed the memorial float, a little Mazda driven by Pete Thorne, his friend and former neighbor. They were in second position, ten yards behind a Fiat Spider carrying the Grand Marshall, a pretty but fragile-looking woman named Nora Durst who’d lost her entire family on October 14th—husband and two young kids—in what was widely considered to be the worst tragedy in all of Mapleton. Nora had reportedly suffered a minor panic attack earlier in the day, claiming she felt dizzy and nauseous and needed to go home, but she’d gotten through the crisis with the help of her sister and a volunteer grief counselor on hand in the event of just such an emergency. She seemed fine now, sitting almost regally in the backseat of the Spider, turning from side to side and wanly raising her hand to acknowledge sporadic bursts of applause from spectators who’d assembled along the route.