Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

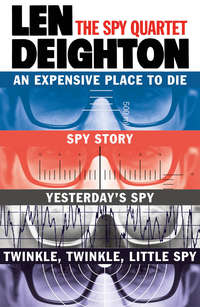

Kitabı oku: «The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy», sayfa 4

6

Maria Chauvet was thirty-two years old. She had kept her looks, her gentleness, her figure, her sexual optimism, her respect for men’s cleverness, her domestication. She had lost her girlhood friends, her shyness, her literary aspirations, her obsession with clothes and her husband. It was a fair swop, she decided. Time had given her a greater measure of independence. She looked around the art gallery without seeing even one person that she really desired to see again. And yet they were her people: the ones she had known since her early twenties, the people who shared her tastes in cinema, travel, sport and books. Now she no longer wished to hear their opinions about the things she enjoyed and she only slightly wished to hear their opinions about the things she hated. The paintings here were awful, they didn’t even show a childish exuberance; they were old, jaded and sad. She hated things that were too real. Ageing was real; as things grew older they became more real, and although age wasn’t something she dreaded she didn’t want to hurry in that direction.

Maria hoped that Loiseau wasn’t going to be violent with the Englishman that he had taken away. Ten years ago she would have said something to Loiseau, but now she had learned discretion, and discretion had become more and more vital in Paris. So had violence, come to that. Maria concentrated on what the artist was saying to her. ‘… the relationships between the spirit of man and the material things with which he surrounds himself …’

Maria had a slight feeling of claustrophobia; she also had a headache. She should take an aspirin, and yet she didn’t, even though she knew it would relieve the pain. As a child she had complained of pain and her mother had said that a woman’s life is accompanied by constant pain. That’s what it’s like to be a woman, her mother had said, to know an ache or a pain all day, every day. Her mother had found some sort of stoic satisfaction in that statement, but the prospect had terrified Maria. It still terrified her and she was determined to disbelieve it. She tried to disregard all pains, as though by acknowledging them she might confess her feminine frailty. She wouldn’t take an aspirin.

She thought of her ten-year-old son. He was living with her mother in Flanders. It was not good for the child to spend a lot of time with elderly people. It was just a temporary measure and yet all the time he was there she felt vaguely guilty about going out to dinner or the cinema, or even evenings like this.

‘Take that painting near the door,’ said the artist. ‘“Holocaust quo vadis?” There you have the vulture that represents the ethereal and …’

Maria had had enough of him. He was a ridiculous fool; she decided to leave. The crowd had become more static now and that always increased her claustrophobia, as did people in the Métro standing motionless. She looked at his flabby face and his eyes, greedy and scavenging for admiration among this crowd who admired only themselves. ‘I’m going now,’ she said. ‘I’m sure the show will be a big success.’

‘Wait a moment,’ he called, but she had timed her escape to coincide with a gap in the crush and she was through the emergency exit, across the cour and away. He didn’t follow her. He probably already had his eye on some other woman who could become interested in art for a couple of weeks.

Maria loved her car, not sinfully, but proudly. She looked after it and drove it well. It wasn’t far to the rue des Saussaies. She positioned the car by the side of the Ministry of the Interior. That was the exit they used at night. She hoped Loiseau wouldn’t keep him there too long. This area near the Élysée Palace was alive with patrols and huge Berliot buses, full of armed cops, the motors running all night in spite of the price of petrol. They wouldn’t do anything to her, of course, but their presence made her uncomfortable. She looked at her wristwatch. Fifteen minutes the Englishman had been there. Now, the sentry was looking back into the courtyard. This must be him. She flashed the headlights of the E-type. Exactly on time; just as Loiseau had told her.

7

The woman laughed. It was a pleasant musical laugh. She said, ‘Not in an E-type. Surely no whore solicits from an E-type. Is it a girl’s car?’ It was the woman from the art gallery.

‘Where I come from,’ I said, ‘they call them hairdressers’ cars.’

She laughed. I had a feeling that she had enjoyed my mistaking her for one of the motorized prostitutes that prowled this district. I got in alongside her and she drove past the Ministry of the Interior and out on to the Malesherbes. She said,

‘I hope Loiseau didn’t give you a bad time.’

‘My resident’s card was out of date.’

‘Poof!’ she scoffed. ‘Do you think I’m a fool? You’d be at the Prefecture if that was the case, not the Ministry of the Interior.’

‘So what do you think he wanted?’

She wrinkled her nose. ‘Who can tell? Jean-Paul said you’d been asking questions about the clinic on the Avenue Foch.’

‘Suppose I told you I wish I’d never heard of the Avenue Foch?’

She put her foot down and I watched the speedometer spin. There was a screech of tyres as she turned on to the Boulevard Haussmann. ‘I’d believe you,’ she said. ‘I wish I’d never heard of it.’

I studied her. She was no longer a girl – perhaps about thirty – dark hair and dark eyes; carefully applied make-up; her clothes were like the car, not brand-new but of good quality. Something in her relaxed manner told me that she had been married and something in her overt friendliness told me she no longer was. She came into the Étoile without losing speed and entered the whirl of traffic effortlessly. She flashed the lights at a taxi that was on a collision course and he sheered away. In the Avenue Foch she turned into a driveway. The gates opened.

‘Here we are,’ she said. ‘Let’s take a look.’

The house was large and stood back in its own piece of ground. At dusk the French shutter themselves tightly against the night. This gaunt house was no exception.

Near to, the cracks in the plaster showed like wrinkles in a face carelessly made-up. The traffic was pounding down the Avenue Foch but that was over the garden wall and far away.

‘So this is the house on the Avenue Foch,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ said the girl.

The big gates closed behind us. A man with a flashlight came out of the shadows. He had a small mongrel dog on a chain.

‘Go ahead,’ said the man. He waved an arm without exerting himself. I guessed that the man was a one-time cop. They are the only people who can stand motionless without loitering. The dog was a German Shepherd in disguise.

We drove down a concrete ramp into a large underground garage. There were about twenty cars there of various expensive foreign makes: Ford GTs, Ferraris, a Bentley convertible. A man standing near the lift called, ‘Leave the keys in.’

Maria slipped off her soft driving shoes and put on a pair of evening shoes. ‘Stay close,’ she said quietly.

I patted her gently. ‘That’s close enough,’ she said.

When we got out of the lift on the ground floor, everything seemed red plush and cut glass – un décor maison-fin-de-siècle – and all of it was tinkling: the laughter, the medals, the ice cubes, the coins, the chandeliers. The main lighting came from ornate gas lamps with pink glass shades; there were huge mirrors and Chinese vases on plinths. Girls in long evening dresses were seated decorously on the wide sweep of the staircase, and in an alcove a barman was pouring drinks as fast as he could work. It was a very fancy affair; it didn’t have the Republican Guard in polished helmets lining the staircase with drawn sabres, but you had the feeling that they’d wanted to come.

Maria leaned across and took two glasses of champagne and some biscuits heaped with caviare. One of the men said, ‘Haven’t seen you for ages.’ Maria nodded without much regret. The man said, ‘You should have been in there tonight. One of them was nearly killed. He’s hurt; badly hurt.’

Maria nodded. Behind me I heard a woman say, ‘He must have been in agony. He wouldn’t have screamed like that unless he had been in agony.’

‘They always do that, it doesn’t mean a thing.’

‘I can tell a real scream from a fake one,’ said the woman.

‘How?’

‘A real scream has no music, it slurs, it … screeches. It’s ugly.’

‘The cuisine,’ said a voice behind me, ‘can be superb; the very finely sliced smoked pork served hot, cold citrus fruits divided in half, bowls of strange hot grains with cream upon it. And those large eggs that they have here in Europe, skilfully fried crisp on the outside and yet the yolk remains almost raw. Sometimes smoked fish of various kinds.’ I turned to face them. The speaker was a middle-aged Chinese in evening dress. He had been speaking to a fellow countryman and as he caught my eye he said, ‘I am explaining to my colleague the fine Anglo-Saxon breakfast that I always enjoy so much.’

‘This is Monsieur Kuang-t’ien,’ said Maria, introducing us.

‘And you, Maria, are exquisite this evening,’ said M. Kuang-t’ien. He spoke a few lines of soft Mandarin.

‘What’s that?’ asked Maria.

‘It is a poem by Shao Hs˘un-mei, a poet and essayist who admired very much the poets of the West. Your dress reminded me of it.’

‘Say it in French,’ said Maria.

‘It is indelicate, in parts.’ He smiled apologetically and began to recite softly.

‘Ah, lusty May is again burning,

A sin is born of a virgin’s kiss;

Sweet tears tempt me, always tempt me

To feel between her breasts with my lips.

Here life is as eternal as death,

As the trembling happiness on a wedding night;

If she is not a rose, a rose all white,

Then she must be redder than the red of blood.’

Maria laughed. ‘I thought you were going to say “she must be redder than the Chinese People’s Republic”.’

‘Ah. Is not possible,’ said M. Kuang-t’ien, and laughed gently.

Maria steered me away from the two Chinese. ‘We’ll see you later,’ she called over her shoulder. ‘He gives me the creeps,’ she whispered.

‘Why?’

‘“Sweet tears”, “if she isn’t white she’ll be red with blood”, death “between breasts”.’ She shook away the thought of it. ‘He has a sick sadistic streak in him that frightens me.’

A man came pushing through the crowd. ‘Who’s your friend?’ he asked Maria.

‘An Englishman,’ said Maria. ‘An old friend,’ she added untruthfully.

‘He looks all right,’ said the man approvingly. ‘But I wished to see you in those high patent shoes.’ He made a clicking sound and laughed, but Maria didn’t. All around us the guests were talking excitedly and drinking. ‘Excellent,’ said a voice I recognized. It was M. Datt. He smiled at Maria. Datt was dressed in a dark jacket, striped trousers and black tie. He looked remarkably calm; unlike so many of his guests, his brow was not flushed nor his collar wrinkled. ‘Are you going in?’ he asked Maria. He looked at his pocket watch. ‘They will begin in two minutes.’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Maria.

‘Of course you are,’ said Datt. ‘You know you will enjoy it.’

‘Not tonight,’ said Maria.

‘Nonsense,’ said Datt gently. ‘Three more bouts. One of them is a gigantic Negro. A splendid figure of a man with gigantic hands.’

Datt lifted one of his own hands to demonstrate, but his eyes watched Maria very closely. She became agitated under his gaze and I felt her grip my hand tightly as though in fear. A buzzer sounded and people finished their drinks and moved towards the rear door.

Datt put his hands on our shoulders and moved us the way the crowd went. As we reached the large double doors I saw into the salon. A wrestling ring was set up in the centre and around it were folding chairs formed up in rows. The salon itself was a magnificent room with golden caryatids, a decorated ceiling, enormous mirrors, fine tapestry and a rich red carpet. As the spectators settled the chandeliers began to dim. The atmosphere was expectant.

‘Take a seat, Maria,’ said Datt. ‘It will be a fine fight; lots of blood.’ Maria’s palm was moist in mine.

‘Don’t be awful,’ said Maria, but she let go of my hand and moved towards the seats.

‘Sit with Jean-Paul,’ said Datt. ‘I want to speak with your friend.’

Maria’s hand trembled. I looked around and saw Jean-Paul for the first time. He was seated alone. ‘Go with Jean-Paul,’ said Datt gently.

Jean-Paul saw us, he smiled. ‘I’ll sit with Jean-Paul,’ said Maria to me.

‘Agreed,’ I said. By the time she was seated, the first two wrestlers were circling each other. One was an Algerian I would guess, the other had bright dyed yellow hair. The man with straw hair lunged forward. The Algerian slid to one side, caught him on the hip and butted him heavily with the top of his head. The crack of head meeting chin was followed by the sharp intake of breath by the audience. On the far side of the room there was a nervous titter of laughter. The mirrored walls showed the wrestlers repeated all around the room. The central light threw heavy shadows under their chins and buttocks, and their legs, painted dark with shadow, emerged into the light as they circled again looking for an opening. Hanging in each corner of the room there was a TV camera linked by landline to monitor screens some distance away. The screens were showing the recorded image.

It was evident that the monitor screens were playing recordings, for the pictures were not clear and the action on the screen took place a few seconds later than the actual fighting. Because of this time-lag between recording and playing back the audience were able to swing their eyes to the monitors each time there was an attack and see it take place again on the screen.

‘Come upstairs,’ said Datt.

‘Very well.’ There was a crash; they were on the mat and the fair man was in a leg lock. His face was contorted. Datt spoke without turning to look. ‘This fighting is rehearsed. The fair-haired man will win after being nearly throttled in the final round.’

I followed him up the magnificent staircase to the first floor. There was a locked door. Clinic. Private. He unlocked the door and ushered me through. An old woman was standing in the corner. I wondered if I was interrupting one of Datt’s interminable games of Monopoly.

‘You were to come next week,’ said Datt.

‘Yes he was,’ said the old woman. She smoothed her apron over her hips like a self-conscious maidservant.

‘Next week would have been better,’ said Datt.

‘That’s true. Next week – without the party – would have been better,’ she agreed.

I said, ‘Why is everyone speaking in the past tense?’

The door opened and two young men came in. They were wearing blue jeans and matching shirts. One of them was unshaven.

‘What’s going on now?’ I asked.

‘The footmen,’ said Datt. ‘Jules on the left. Albert on the right. They are here to see fair play. Right?’ They nodded without smiling. Datt turned to me. ‘Just lie down on the couch.’

‘No.’

‘What?’

‘I said no I won’t lie down on the couch.’

Datt tutted. He was a little put out. There wasn’t any mockery or sadism in the tutting. ‘There are four of us here,’ he explained. ‘We are not asking you to do anything unreasonable, are we? Please lie down on the couch.’

I backed towards the side table. Jules came at me and Albert was edging around to my left side. I came back until the edge of the table was biting my right hip so I knew exactly how my body was placed in relation to it. I watched their feet. You can tell a lot about a man from the way he places his feet. You can tell the training he has had, whether he will lunge or punch from a stationary position, whether he will pull you or try to provoke you into a forward movement. Jules was still coming on. His hands were flat and extended. About twenty hours of gymnasium karate. Albert had the old course d’échalotte look about him. He was used to handling heavyweight, over-confident drunks. Well, he’d find out what I was; yes, I thought: a heavyweight, over-confident drunk. Heavyweight Albert was coming on like a train. A boxer; look at his feet. A crafty boxer who would give you all the fouls; the butts, kidney jabs and back of the head stuff, but he fancied himself as a jab-and-move-around artist. I’d be surprised to see him aim a kick in the groin with any skill. I brought my hands suddenly into sparring position. Yes, his chin tucked in and he danced his weight around on the balls of his feet. ‘Fancy your chances, Albert?’ I jeered. His eyes narrowed. I wanted him angry. ‘Come on soft boy,’ I said. ‘Bite on a piece of bare knuckle.’

I saw the cunning little Jules out of the corner of my eye. He was smiling. He was coming too, smooth and cool inch by inch, hands flat and trembling for the killer cut.

I made a slight movement to keep them going. If they once relaxed, stood up straight and began to think, they could eat me up.

Heavyweight Albert’s hands were moving, foot forward for balance, right hand low and ready for a body punch while Jules chopped at my neck. That was the theory. Surprise for Albert: my metal heelpiece going into his instep. You were expecting a punch in the buffet or a kick in the groin, Albert, so you were surprised when a terrifying pain hit your instep. Difficult for the balancing too. Albert leaned forward to console his poor hurt foot. Second surprise for Albert: under-swung flat hand on the nose; nasty. Jules is coming, cursing Albert for forcing his hand. Jules is forced to meet me head down. I felt the edge of the table against my hip. Jules thinks I’m going to lean into him. Surprise for Jules: I lean back just as he’s getting ready to give me a hand edge on the corner of the neck. Second surprise for Jules: I do lean in after all and give him a fine glass paperweight on the earhole at a range of about eighteen inches. The paperweight seems none the worse for it. Now’s the chance to make a big mistake. Don’t pick up the paperweight. Don’t pick up the paperweight. Don’t pick up the paperweight. I didn’t pick it up. Go for Datt, he’s standing he’s mobile and he’s the one who is mentally the driving force in the room.

Down Datt. He’s an old man but don’t underrate him. He’s large and weighty and he’s been around. What’s more he’ll use anything available; the old maidservant is careful, discriminating, basically not aggressive. Go for Datt. Albert is rolling over and may come up to one side of my range of vision. Jules is motionless. Datt is moving around the desk; so it will have to be a missile. An inkstand, too heavy. A pen-set will fly apart. A vase: unwieldy. An ashtray. I picked it up, Datt was still moving, very slowly now, watching me carefully, his mouth open and white hair disarrayed as though he had been in the scuffle. The ashtray is heavy and perfect. Careful, you don’t want to kill him. ‘Wait,’ Datt says hoarsely. I waited. I waited about ten seconds, just long enough for the woman to come behind me with a candlestick. She was basically not aggressive, the maidservant. I was only unconscious thirty minutes, they told me.

8

I was saying ‘You are not basically aggressive’ as I regained consciousness.

‘No,’ said the woman as though it was a grave shortcoming. ‘It is true.’ I couldn’t see either of them from where I was full length on my back. She switched the tape recorder on. There was the sudden intimate sound of a girl sobbing. ‘I want it recording,’ she said, but the sound of the girl became hysterical and she began to scream as though someone was torturing her. ‘Switch that damn thing off,’ Datt called. It was strange to see him disturbed, he was usually so calm. She turned the volume control the wrong way and the sound of the screams went right through my head and made the floor vibrate.

‘The other way,’ screamed Datt. The sound abated, but the tape was still revolving and the sound could just be heard; the girl was sobbing again. The desperate sound was made even more helpless by its diminished volume, like someone abandoned or locked out.

‘What is it?’ asked the maidservant. She shuddered but seemed reluctant to switch off; finally she did so and the reels clicked to a standstill.

‘What’s it sound like?’ said Datt. ‘It’s a girl sobbing and screaming.’

‘My God,’ said the maidservant.

‘Calm down,’ said Datt. ‘It’s for amateur theatricals. It’s just for amateur theatricals,’ he said to me.

‘I didn’t ask you,’ I said.

‘Well, I’m telling you.’ The servant woman turned the reel over and rethreaded it. I felt fully conscious now and I sat up so that I could see across the room. The girl Maria was standing by the door, she had her shoes in her hand and a man’s raincoat over her shoulders. She was staring blankly at the wall and looking miserable. There was a boy sitting near the gas fire. He was smoking a small cheroot, biting at the end which had become frayed like a rope end, so that each time he pulled it out of his mouth he twisted his face up to find the segments of leaf and discharge them on the tongue-tip. Datt and the old maidservant had dressed up in those old-fashioned-looking French medical gowns with high buttoned collars. Datt was very close to me and did a patent-medicine commercial while sorting through a trayful of instruments.

‘Has he had the LSD?’ asked Datt.

‘Yes,’ said the maid. ‘It should start working soon.’

‘You will answer any questions we ask,’ said Datt to me.

I knew he was right: a well-used barbiturate could nullify all my years of training and experience and make me as co-operatively garrulous as a tiny child. What the LSD would do was anyone’s guess.

What a way to be defeated and laid bare. I shuddered, Datt patted my arm.

The old woman was assisting him. ‘The Amytal,’ said Datt, ‘the ampoule, and the syringe.’

She broke the ampoule and filled the syringe. ‘We must work fast,’ said Datt. ‘It will be useless in thirty minutes; it has a short life. Bring him forward, Jules, so that she can block the vein. Dab of alcohol, Jules, no need to be inhuman.’

I felt hot breath on the back of my neck as Jules laughed dutifully at Datt’s little joke.

‘Block the vein now,’ said Datt. She used the arm muscle to compress the vein of the forearm and waited a moment while the veins rose. I watched the process with interest, the colours of the skin and the metal were shiny and unnaturally bright. Datt took the syringe and the old woman said, ‘The small vein on the back of the hand. If it clots we’ve still got plenty of patent ones left.’

‘A good thought,’ said Datt. He did a triple jab under the skin and searched for the vein, dragging at the plunger until the blood spurted back a rich gusher of red into the glass hypodermic. ‘Off,’ said Datt. ‘Off or he’ll bruise. It’s important to avoid that.’

She released the arm vein and Datt stared at his watch, putting the drug into the vein at a steady one cc per minute.

‘He’ll feel a great release in a moment, an orgastic response. Have the Megimide ready. I want him responding for at least fifteen minutes.’

M. Datt looked up at me. ‘Who are you?’ he asked in French. ‘Where are you, what day is it?’

I laughed. His damned needle was going into someone else’s arm, that was the only funny thing about it. I laughed again. I wanted to be absolutely sure about the arm. I watched the thing carefully. There was the needle in that patch of white skin but the arm didn’t fit on to my shoulder. Fancy him jabbing someone else. I was laughing more now so that Jules steadied me. I must have been jostling whoever was getting the injection because Datt had trouble holding the needle in.

‘Have the Megimide and the cylinder ready,’ said M. Datt, who had hairs – white hairs – in his nostrils. ‘Can’t be too careful. Maria, quickly, come closer, we’ll need you now, bring the boy closer; he’ll be the witness if we need one.’ M. Datt dropped something into the white enamel tray with a tremendous noise. I couldn’t see Maria now, but I smelled the perfume – I’d bet it was Ma Griffe, heavy and exotic, oh boy! It’s orange-coloured that smell. Orange-coloured with a sort of silky touch to it. ‘That’s good,’ said M. Datt, and I heard Maria say orange-coloured too. Everyone knows, I thought, everyone knows the colour of Ma Griffe perfume.

The huge glass orange fractured into a million prisms, each one a brilliant, like the Sainte Chapelle at high noon, and I slid through the coruscating light as a punt slides along a sleepy bywater, the white cloud low and the colours gleaming and rippling musically under me.

I looked at M. Datt’s face and I was frightened. His nose had grown enormous, not just large but enormous, larger than any nose could possibly be. I was frightened by what I saw because I knew that M. Datt’s face was the same as it had always been, and that it was my awareness that had distorted. Yet even knowing that the terrible disfigurement had happened inside my mind, not on M. Datt’s face, did not change the image; M. Datt’s nose had grown to a gigantic size.

‘What day is it?’ Maria was asking. I told her. ‘It’s just a gabble,’ she said. ‘Too fast to really understand.’ I listened but I could hear no one gabbling. Her eyes were soft and unblinking. She asked me my age, my date of birth and a lot of personal questions. I told her as much, and more, than she asked. The scar on my knee and the day my uncle planted the pennies in the tall tree. I wanted her to know everything about me. ‘When we die,’ my grandmother told me, ‘we shall all go to Heaven,’ she surveyed her world, ‘for surely this is Hell?’ ‘Old Mr Gardner had athlete’s foot, whose was the other foot?’ Recitation: ‘Let me like a soldier fall …’

‘A desire,’ said M. Datt’s voice, ‘to externalize, to confide.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed.

‘I’ll bring him up with the Megimide if he goes too far,’ said M. Datt. ‘He’s fine like that. Fine response. Fine response.’

Maria repeated everything I said, as though Datt could not hear it himself. She said each thing not once but twice. I said it, then she said it, then she said it again differently; sometimes very differently so that I corrected her, but she was indifferent to my corrections and spoke in that fine voice she had; a round reed-clear voice full of song and sorrow like an oboe at night.

Now and again there was the voice of Datt deep and distant, perhaps from the next room. They seemed to think and speak so slowly. I answered Maria leisurely but it was ages before the next question came. I tired of the long pauses eventually. I filled the gaps telling them anecdotes and interesting stuff I’d read. I felt I’d known Maria for years and I remember saying ‘transference’, and Maria said it too, and Datt seemed very pleased. I found it was quite easy to compose my answers in poetry – not all of it rhymed, mind you – but I phrased it carefully. I could squeeze those damned words like putty and hand them to Maria, but sometimes she dropped them on to the marble floor. They fell noiselessly, but the shadows of them reverberated around the distant walls and furniture. I laughed again, and wondered whose bare arm I was staring at. Mind you, that wrist was mine, I recognized the watch. Who’d torn that shirt? Maria kept saying something over and over, a question perhaps. Damned shirt cost me £3.10s and now they’d torn it. The torn fabric was exquisite, detailed and jewel-like. Datt’s voice said, ‘He’s going now: it’s very short duration, that’s the trouble with it.’

Maria said, ‘Something about a shirt, I can’t understand, it’s so fast.’

‘No matter,’ said Datt. ‘You’ve done a good job. Thank God you were here.’

I wondered why they were speaking in a foreign language. I had told them everything. I had betrayed my employers, my country, my department. They had opened me like a cheap watch, prodded the main spring and laughed at its simple construction. I had failed and failure closed over me like a darkroom blind coming down.

Dark. Maria’s voice said, ‘He’s gone,’ and I went, a white seagull gliding through black sky, while beneath me the even darker sea was welcoming and still. And deep, and deep and deep.