Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

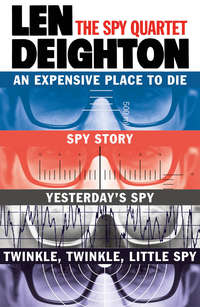

Kitabı oku: «The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy», sayfa 6

11

We walked and talked and forgot the time. ‘Your place,’ I said finally to Maria. ‘You have central heating, the sink is firmly fixed to the wall, you don’t share the w.c. with eight other people and there are gramophone records I haven’t even read the labels on yet. Let’s go to your place.’

‘Very well,’ she said, ‘since you are so flattering about its advantages.’ I kissed her ear gently. She said, ‘But suppose the landlord throws you out?’

‘Are you having an affair with your landlord?’

She smiled and gave me a forceful blow that many French women conveniently believe is a sign of affection.

‘I’m not washing any more shirts,’ she said. ‘We’ll take a cab to your place and pick up some linen.’

We bargained with three taxi-drivers, exchanging their directional preferences with ours; finally one of them weakened and agreed to take us to the Petit Légionnaire.

I let myself into my room with Maria just behind me. Joey chirped politely when I switched on the light.

‘My God,’ said Maria, ‘someone’s turned you over.’

I picked up a heap of shirts that had landed in the fireplace.

‘Yes,’ I said. Everything from the drawers and cupboards had been tipped on to the floor. Letters and cheque stubs were scattered across the sofa and quite a few things were broken. I let the armful of shirts fall to the floor again, I didn’t know where to begin on it. Maria was more methodical, she began to sort through the clothes, folding them and putting trousers and jackets on the hangers. I picked up the phone and dialled the number Loiseau had given me.

‘Un sourire est différent d’un rire,’ I said. France is one place where the romance of espionage will never be lost, I thought. Loiseau said ‘Hello.’

‘Have you turned my place over, Loiseau?’ I said.

‘Are you finding the natives hostile?’ Loiseau asked.

‘Just answer the question,’ I said.

‘Why don’t you answer mine?’ said Loiseau.

‘It’s my jeton,’ I said. ‘If you want answers you buy your own call.’

‘If my boys had done it you wouldn’t have noticed.’

‘Don’t get blasé. Loiseau. The last time your boys did it – five weeks back – I did notice. Tell ’em if they must smoke, to open the windows; that cheap pipe tobacco makes the canary’s eyes water.’

‘But they are very tidy,’ said Loiseau. ‘They wouldn’t make a mess. If it’s a mess you are complaining of.’

‘I’m not complaining about anything,’ I said. ‘I’m just trying to get a straight answer to a simple question.’

‘It’s too much to ask of a policeman,’ said Loiseau. ‘But if there is anything damaged I’d send the bill to Datt.’

‘If anything gets damaged it’s likely to be Datt,’ I said.

‘You shouldn’t have said that to me,’ said Loiseau. ‘It was indiscreet, but bonne chance anyway.’

‘Thanks,’ I said and hung up.

‘So it wasn’t Loiseau?’ said Maria, who had been listening.

‘What makes you think that?’ I asked.

She shrugged. ‘The mess here. The police would have been careful. Besides, if Loiseau admitted that the police have searched your home other times why should he deny that they did it this time?’

‘Your guess is as good as mine,’ I said. ‘Perhaps Loiseau did it to set me at Datt’s throat.’

‘So you were deliberately indiscreet to let him think he’d succeeded?’

‘Perhaps.’ I looked into the torn seat of the armchair. The horse-hair stuffing had been ripped out and the case of documents that the courier had given me had disappeared. ‘Gone,’ said Maria.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Perhaps you did translate my confession correctly after all.’

‘It was an obvious place to look. In any case I was not the only person to know your “secret”: this evening you told Byrd that you kept your money there.’

‘That’s true, but was there time for anyone to act on that?’

‘It was two hours ago,’ said Maria. ‘He could have phoned. There was plenty of time.’

We began to sort out the mess. Fifteen minutes passed, then the phone rang. It was Jean-Paul.

‘I’m glad to catch you at home,’ he said. ‘Are you alone?’

I held a finger up to my lips to caution Maria. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I’m alone. What is it?’

‘There’s something I wanted to tell you without Byrd hearing.’

‘Go ahead.’

‘Firstly. I have good connections in the underworld and the police. I am certain that you can expect a burglary within a day or so. Anything you treasure should be put into a bank vault for the time being.’

‘You’re too late,’ I said. ‘They were here.’

‘What a fool I am. I should have told you earlier this evening. It might have been in time.’

‘No matter,’ I said. ‘There was nothing here of value except the typewriter.’ I decided to solidify the freelance-writer image a little. ‘That’s the only essential thing. What else did you want to tell me?’

‘Well that policeman, Loiseau, is a friend of Byrd.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘Byrd was in the war with Loiseau’s brother.’

‘Right,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘Now Inspector Loiseau was asking Byrd about you earlier today. Byrd told Inspector Loiseau that …’

‘Well, come on.’

‘He told him you are a spy. A spy for the West Germans.’

‘Well that’s good family entertainment. Can I get invisible ink and cameras at a trade discount?’

‘You don’t know how serious such a remark can be in France today. Loiseau is forced to take notice of such a remark no matter how ridiculous it may seem. And it’s impossible for you to prove that it’s not true.’

‘Well thanks for telling me,’ I said. ‘What do you suggest I do about it?’

‘There is nothing you can do for the moment,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘But I shall try to find out anything else Byrd says of you, and remember that I have very influential friends among the police. Don’t trust Maria whatever you do.’

Maria’s ear went even closer to the receiver. ‘Why’s that?’ I asked. Jean-Paul chuckled maliciously. ‘She’s Loiseau’s ex-wife, that’s why. She too is on the payroll of the Sûreté.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘See you in court.’

Jean-Paul laughed at that remark – or perhaps he was still laughing at the one before.

12

Maria applied her make-up with unhurried precision. She was by no means a cosmetics addict but this morning she was having lunch with Chief Inspector Loiseau. When you had lunch with an ex-husband you made quite sure that he realized what he had lost. The pale-gold English wool suit that she had bought in London. He’d always thought her a muddle-headed fool so she’d be as slick and businesslike as possible. And the new plain-front shoes; no jewellery. She finished the eyeliner and the mascara and began to apply the eye-shadow. Not too much; she had been wearing much too much the other evening at the art gallery. You have a perfect genius, she told herself severely, for getting yourself involved in situations where you are a minor factor instead of a major factor. She smudged the eye-shadow, cursed softly, removed it and began again. Will the Englishman appreciate the risk you are taking? Why not tell M. Datt the truth of what the Englishman said? The Englishman is interested only in his work, as Loiseau was interested only in his work. Loiseau’s love-making was efficient, just as his working day was. How can a woman compete with a man’s work? Work is abstract and intangible, hypnotic and lustful; a woman is no match for it. She remembered the nights she had tried to fight Loiseau’s work, to win him away from the police and its interminable paperwork and its relentless demands upon their time together. She remembered the last bitter argument about it. Loiseau had kissed her passionately in a way he had never done before and they had made love and she had clung to him, crying silently in the sudden release of tension, for at that moment she knew that they would separate and divorce, and she had been right.

Loiseau still owned a part of her, that’s why she had to keep seeing him. At first they had been arranging details of the legal separation, custody of the boy, then agreements about the house. Then Loiseau had asked her to do small tasks for the police department. She knew that he could not face the idea of losing her completely. They had become dispassionate and sincere, for she no longer feared losing him; they were like brother and sister now, and yet … she sighed. Perhaps it all could have been different; Loiseau still had an insolent confidence that made her pleased, almost proud, to be with him. He was a man, and that said everything there was to say about him. Men were unreasonable. Her work for the Sûreté had become quite important. She was pleased with the chance to show Loiseau how efficient and businesslike she could be, but Loiseau would never acknowledge it. Men were unreasonable. All men. She remembered a certain sexual mannerism of his, and smiled. All men set tasks and situations in which anything a woman thinks, says, or does will be wrong. Men demand that women should be inventive, shameless whores, and then reject them for not being motherly enough. They want them to attract their men friends and then they get jealous about it.

She powdered her lipstick to darken it and then pursed her lips and gave her face one final intent glare. Her eyes were good, the pupils were soft and the whites gleaming. She went to meet her ex-husband.

13

Loiseau had been smoking too much and not getting enough sleep. He kept putting a finger around his metal wristwatch band; Maria remembered how she had dreaded those nervous mannerisms that always preceded a row. He gave her coffee and remembered the amount of sugar she liked. He remarked on her suit and her hair and liked the plain-fronted shoes. She knew that sooner or later he would mention the Englishman.

‘Those same people have always fascinated you,’ he said. ‘You are a gold-digger for brains, Maria. You are drawn irresistibly to men who think only of their work.’

‘Men like you,’ said Maria. Loiseau nodded.

He said, ‘He’ll just bring you trouble, that Englishman.’

‘I’m not interested in him,’ said Maria.

‘Don’t lie to me,’ said Loiseau cheerfully. ‘Reports from seven hundred policemen go across this desk each week. I also get reports from informers and your concierge is one of them.’

‘The bitch.’

‘It’s the system,’ said Loiseau. ‘We have to fight the criminal with his own weapons.’

‘Datt gave him an injection of something to question him.’

‘I know,’ said Loiseau.

‘It was awful,’ said Maria.

‘Yes, I’ve seen it done.’

‘It’s like a torture. A filthy business.’

‘Don’t lecture me,’ said Loiseau. ‘I don’t like Amytal injections and I don’t like Monsieur Datt or that clinic, but there’s nothing I can do about it.’ He sighed. ‘You know that, Maria.’ But Maria didn’t answer. ‘That house is safe from even my wide powers.’ He smiled as if the idea of him endangering anything was absurd. ‘You deliberately translated the Englishman’s confession incorrectly, Maria,’ Loiseau accused her.

Maria said nothing. Loiseau said, ‘You told Monsieur Datt that the Englishman is working under my orders. Be careful what you say or do with these people. They are dangerous – all of them are dangerous; your flashy boyfriend is the most dangerous of all.’

‘Jean-Paul you mean?’

‘The playboy of the Buttes Chaumont,’ said Loiseau sarcastically.

‘Don’t keep calling him my boyfriend,’ said Maria.

‘Come come, I know all about you,’ said Loiseau, using a phrase and a manner that he employed in interrogations. ‘You can’t resist these flashy little boys and the older you get the more vulnerable you become to them.’ Maria was determined not to show anger. She knew that Loiseau was watching her closely and she felt her cheeks flushing in embarrassment and anger.

‘He wants to work for me,’ said Loiseau.

‘He likes to feel important,’ explained Maria, ‘as a child does.’

‘You amaze me,’ said Loiseau, taking care to be unamazed. He stared at her in a way that a Frenchman stares at a pretty girl on the street. She knew that he fancied her sexually and it comforted her, not to frustrate him, but because to be able to interest him was an important part of their new relationship. She felt that in some ways this new feeling she had for him was more important than their marriage had been, for now they were friends, and friendship is less infirm and less fragile than love.

‘You mustn’t harm Jean-Paul because of me,’ said Maria.

‘I’m not interested in Drugstore cowboys,’ said Loiseau. ‘At least not until they are caught doing something illegal.’

Maria took out her cigarettes and lit one as slowly as she knew how. She felt all the old angers welling up inside her. This was the Loiseau she had divorced; this stern, unyielding man who thought that Jean-Paul was an effeminate gigolo merely because he took himself less seriously than Loiseau ever could. Loiseau had crushed her, had reduced her to a piece of furniture, to a dossier – the dossier on Maria; and now the dossier was passed over to someone else and Loiseau thought the man concerned would not handle it as competently as he himself had done. Long ago Loiseau had produced a cold feeling in her and now she felt it again. This same icy scorn was poured upon anyone who smiled or relaxed; self-indulgent, complacent, idle – these were Loiseau’s words for anyone without his self-flagellant attitude to work. Even the natural functions of her body seemed something against the law when she was near Loiseau. She remembered the lengths she went to to conceal the time of her periods in case he should call her to account for them, as though they were the mark of some ancient sin.

She looked up at him. He was still talking about Jean-Paul. How much had she missed – a word, a sentence, a lifetime? She didn’t care. Suddenly the room seemed cramped and the old claustrophobic feeling that made her unable to lock the bathroom door – in spite of Loiseau’s rages about it – made this room unbearably small. She wanted to leave.

‘I’ll open the door,’ she said. ‘I don’t want the smoke to bother you.’

‘Sit down,’ he said. ‘Sit down and relax.’

She felt she must open the door.

‘Your boyfriend Jean-Paul is a nasty little casserole,’6 said Loiseau, ‘and you might just as well face up to it. You accuse me of prying into other people’s lives: well perhaps that’s true, but do you know what I see in those lives? I see things that shock and appal me. That Jean-Paul. What is he but a toe-rag for Datt, running around like a filthy little pimp. He is the sort of man that makes me ashamed of being a Frenchman. He sits all day in the Drugstore and the other places that attract the foreigners. He holds a foreign newspaper pretending that he is reading it – although he speaks hardly a word of any foreign language – hoping to get into conversation with some pretty little girl secretary or better still a foreign girl who can speak French. Isn’t that a pathetic thing to see in the heart of the most civilized city in the world? This lout sitting there chewing Hollywood chewing-gum and looking at the pictures in Playboy. Speak to him about religion and he will tell you how he despises the Catholic Church. Yet every Sunday when he’s sitting there with his hamburger looking so transatlantique, he’s just come from Mass. He prefers foreign girls because he’s ashamed of the fact that his father is a metal-worker in a junk yard and foreign girls are less likely to notice his coarse manners and phoney voice.’

Maria had spent years hoping to make Loiseau jealous and now, years after their divorce had been finalized, she had succeeded. For some reason the success brought her no pleasure. It was not in keeping with Loiseau’s calm, cold, logical manner. Jealousy was weakness, and Loiseau had very few weaknesses.

Maria knew that she must open the door or faint. Although she knew this slight dizziness was claustrophobia she put out the half-smoked cigarette in the hope that it would make her feel better. She stubbed it out viciously. It made her feel better for about two minutes. Loiseau’s voice droned on. How she hated this office. The pictures of Loiseau’s life, photos of him in the army: slimmer and handsome, smiling at the photographer as if to say ‘This is the best time of our lives, no wives, no responsibility.’ The office actually smelled of Loiseau’s work; she remembered that brown card that wrapped the dossiers and the smell of the old files that had come up from the cellars after goodness knows how many years. They smelled of stale vinegar. It must have been something in the paper, or perhaps the fingerprint ink.

‘He’s a nasty piece of work, Maria,’ said Loiseau. ‘I’d even go so far as to say evil. He took three young German girls out to that damned cottage he has near Barbizon. He was with a couple of his so-called artist friends. They raped those girls, Maria, but I couldn’t get them to give evidence. He’s an evil fellow; we have too many like him in Paris.’

Maria shrugged, ‘The girls should not have gone there, they should have known what to expect. Girl tourists – they only come here to be raped; they think it’s romantic to be raped in Paris.’

‘Two of these girls were sixteen years old, Maria, they were children; the other only eighteen. They’d asked your boyfriend the way to their hotel and he offered them a lift there. Is this what has happened to our great and beautiful city, that a stranger can’t ask the way without risking assault?’

Outside the weather was cold. It was summer and yet the wind had an icy edge. Winter arrives earlier each year, thought Maria. Thirty-two years old, it’s August again but already the leaves die, fall and are discarded by the wind. Once August was hot midsummer, now August was the beginning of autumn. Soon all the seasons would merge, spring would not arrive and she would know the menopausal womb-winter that is half-life.

‘Yes,’ said Maria. ‘That’s what has happened.’ She shivered.

14

It was two days later when I saw M. Datt again. The courier was due to arrive any moment. He would probably be grumbling and asking for my report about the house on the Avenue Foch. It was a hard grey morning, a slight haze promising a scorching hot afternoon. In the Petit Légionnaire there was a pause in the business of the day, the last petit déjeuner had been served but it was still too early for lunch. Half a dozen customers were reading their newspapers or staring across the street watching the drivers argue about parking space. M. Datt and both the Tastevins were at their usual table, which was dotted with coffee pots, cups and tiny glasses of Calvados. Two taxi-drivers played ‘ping-foot’, swivelling the tiny wooden footballers to smack the ball across the green felt cabinet. M. Datt called to me as I came down for breakfast.

‘This is terribly late for a young man to wake,’ he called jovially. ‘Come and sit with us.’ I sat down, wondering why M. Datt had suddenly become so friendly. Behind me the ‘ping-foot’ players made a sudden volley. There was a clatter as the ball dropped through the goal-mouth and a mock cheer of triumph.

‘I owe you an apology,’ said M. Datt. ‘I wanted to wait a few days before delivering it so that you would find it in yourself to forgive me.’

‘That humble hat doesn’t fit,’ I said. ‘Go a size larger.’

M. Datt opened his mouth and rocked gently. ‘You have a fine sense of humour,’ he proclaimed once he had got himself under control.

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘You are quite a joker yourself.’

M. Datt’s mouth puckered into a smile like a carelessly ironed shirt-collar. ‘Oh I see what you mean,’ he said suddenly and laughed. ‘Ha-ha-ha,’ he laughed. Madame Tastevin had spread the Monopoly board by now and dealt us the property cards to speed up the game. The courier was due to arrive, but getting closer to M. Datt was the way the book would do it.

‘Hotels on Lecourbe and Belleville,’ said Madame Tastevin.

‘That’s what you always do,’ said M. Datt. ‘Why don’t you buy railway stations instead?’

We threw the dice and the little wooden discs went trotting around the board, paying their rents and going to prison and taking their chances just like humans. ‘A voyage of destruction,’ Madame Tastevin said it was.

‘That’s what all life is,’ said M. Datt. ‘We start to die on the day we are born.’

My chance card said ‘Faites des réparations dans toutes vos maisons’ and I had to pay 2,500 francs on each of my houses. It almost knocked me out of the game but I scraped by. As I finished settling up I saw the courier cross the terrasse. It was the same man who had come last time. He took it very slow and stayed close to the wall. A coffee crème and a slow appraisal of the customers before contacting me. Professional. Sift the tails off and duck from trouble. He saw me but gave no sign of doing so.

‘More coffee for all of us,’ said Madame Tastevin. She watched the two waiters laying the tables for lunch, and now she called out to them, ‘That glass is smeary’, ‘Use the pink napkins, save the white ones for evening’, ‘Be sure there is enough terrine today. I’ll be angry if we run short.’ The waiters were keen that Madame shouldn’t get angry, they moved anxiously, patting the cloths and making microscopic adjustments to the placing of the cutlery. The taxi-drivers decided upon another game and there was a rattle of wooden balls as the coin went into the slot.

The courier had brought out a copy of L’Express and was reading it and sipping abstractedly at his coffee. Perhaps he’ll go away, I thought, perhaps I won’t have to listen to his endless official instructions. Madame Tastevin was in dire straits, she mortgaged three of her properties. On the cover of L’Express there was a picture of the American Ambassador to France shaking hands with a film star at a festival.

M. Datt said, ‘Can I smell a terrine cooking? What a good smell.’

Madame nodded and smiled. ‘When I was a girl all Paris was alive with smells; oil paint and horse sweat, dung and leaky gas lamps and everywhere the smell of superb French cooking. Ah!’ She threw the dice and moved. ‘Now,’ she said, ‘it smells of diesel, synthetic garlic, hamburgers and money.’

M. Datt said, ‘Your dice.’

‘Okay,’ I told him. ‘But I must go upstairs in a moment. I have so much work to do.’ I said it loud enough to encourage the courier to order a second coffee.

Landing on the Boul des Capucines destroyed Madame Tastevin.

‘I’m a scientist,’ said M. Datt, picking up the pieces of Madame Tastevin’s bankruptcy. ‘The scientific method is inevitable and true.’

‘True to what?’ I asked. ‘True to scientists, true to history, true to fate, true to what?’

‘True to itself,’ said Datt.

‘The most evasive truth of all,’ I said.

M. Datt turned to me, studied my face and wet his lips before beginning to talk. ‘We have begun in a bad … a silly way.’ Jean-Paul came into the café – he had been having lunch there every day lately. He waved airily to us and bought cigarettes at the counter.

‘But there are certain things that I don’t understand,’ Datt continued. ‘What are you doing carrying a case-load of atomic secrets?’

‘And what are you doing stealing it?’

Jean-Paul came across to the table, looked at both of us and sat down.

‘Retrieving,’ said Datt. ‘I retrieved it for you.’

‘Then let’s ask Jean-Paul to remove his gloves,’ I said.

Jean-Paul watched M. Datt anxiously. ‘He knows,’ said M. Datt. ‘Admit it, Jean-Paul.’

‘On account,’ I explained to Jean-Paul, ‘of how we began in a bad and silly way.’

‘I said that,’ said M. Datt to Jean-Paul. ‘I said we had started in a bad and silly way and now we want to handle things differently.’

I leaned across and peeled back the wrist of Jean-Paul’s cotton gloves. The flesh was stained violet with ‘nin’.7

‘Such an embarrassment for the boy,’ said M. Datt, smiling. Jean-Paul glowered at him.

‘Do you want to buy the documents?’ I asked.

M. Datt shrugged. ‘Perhaps. I will give you ten thousand new francs, but if you want more than that I would not be interested.’

‘I’ll need double that,’ I said.

‘And if I decline?’

‘You won’t get every second sheet, which I removed and deposited elsewhere.’

‘You are no fool,’ said M. Datt. ‘To tell you the truth the documents were so easy to get from you that I suspected their authenticity. I’m glad to find you are no fool.’

‘There are more documents,’ I said. ‘A higher percentage will be Xerox copies but you probably won’t mind that. The first batch had a high proportion of originals to persuade you of their

authenticity, but it’s too risky to do that regularly.’

‘Whom do you work for?’

‘Never mind who I work for. Do you want them or not?’

M. Datt nodded, smiled grimly and said, ‘Agreed, my friend. Agreed.’ He waved an arm and called for coffee. ‘It’s just curiosity. Not that your documents are anything like my scientific interests. I shall use them merely to stimulate my mind. Then they will be destroyed. You can have them back …’ The courier finished his coffee and then went upstairs, trying to look as though he was going no farther than the toilets on the first floor.

I blew my nose noisily and then lit a cigarette. ‘I don’t care what you do with them, monsieur. My fingerprints are not on the documents and there is no way to connect them with me; do as you wish with them. I don’t know if these documents connect with your work. I don’t even know what your work is.’

‘My present work is scientific,’ explained Datt. ‘I run my clinic to investigate the patterns of human behaviour. I could make much more money elsewhere, my qualifications are good. I am an analyst. I am still a good doctor. I could lecture on several different subjects: upon oriental art, Buddhism or even Marxist theory. I am considered an authority on Existentialism and especially upon Existentialist psychology; but the work I am doing now is the work by which I will be known. The idea of being remembered after death becomes important as one gets old.’ He threw the dice and moved past Départ. ‘Give me my twenty thousand francs,’ he said.

‘What do you do at this clinic?’ I peeled off the toy money and passed it to him. He counted it and stacked it up.

‘People are blinded by the sexual nature of my work. They fail to see it in its true light. They think only of the sex activity.’ He sighed. ‘It’s natural, I suppose. My work is important merely because people cannot consider the subject objectively. I can; so I am one of the few men who can control such a project.’

‘You analyse the sexual activity?’

‘Yes,’ said Datt. ‘No one does anything they do not wish to do. We do employ girls but most of the people who go to the house go there as couples, and they leave in couples. I’ll buy two more houses.’

‘The same couples?’

‘Not always,’ said Datt. ‘But that is not necessarily a thing to be deplored. People are mentally in bondage, and their sexual activity is the cipher which can help to explain their problems. You’re not collecting your rent.’ He pushed it over to me.

‘You are sure that you are not rationalizing the ownership of a whorehouse?’

‘Come along there now and see,’ said Datt. ‘It is only a matter of time before you land upon my hotels in the Avenue de la République.’ He shuffled his property cards together. ‘And then you are no more.’

‘You mean the clinic is operating at noon?’

‘The human animal,’ said Datt, ‘is unique in that its sexual cycle continues unabated from puberty to death.’ He folded up the Monopoly board.

It was getting hotter now, the sort of day that gives rheumatism a jolt and expands the Eiffel Tower six inches. ‘Wait a moment,’ I said to Datt. ‘I’ll go up and shave. Five minutes?’

‘Very well,’ said Datt. ‘But there’s no real need to shave, you won’t be asked to participate.’ He smiled.

I hurried upstairs, the courier was waiting inside my room. ‘They bought it?’

‘Yes,’ I said. I repeated my conversation with M. Datt.

‘You’ve done well,’ he said.

‘Are you running me?’ I lathered my face carefully and began shaving.

‘No. Is that where they took it from, where the stuffing is leaking out?’

‘Yes. Then who is?’

‘You know I can’t answer that. You shouldn’t even ask me. Clever of them to think of looking there.’

‘I told them where it was. I’ve never asked before,’ I said, ‘but whoever is running me seems to know what these people do even before I know. It’s someone close, someone I know. Don’t keep poking at it. It’s only roughly stitched back.’

‘That at least is wrong,’ said the courier. ‘It’s no one you know or have ever met. How did you know who took the case?’

‘You’re lying. I told you not to keep poking at it. Nin; it colours your flesh. Jean-Paul’s hands were bright with it.’

‘What colour?’

‘You’ll be finding out,’ I said. ‘There’s plenty of nin still in there.’

‘Very funny.’

‘Well who told you to poke your stubby peasant fingers into my stuffing?’ I said. ‘Stop messing about and listen carefully. Datt is taking me to the clinic, follow me there.’

‘Very well,’ said the courier without enthusiasm. He wiped his hands on a large handkerchief.

‘Make sure I’m out again within the hour.’

‘What am I supposed to do if you are not out within the hour?’ he asked.

‘I’m damned if I know,’ I said. They never ask questions like that in films. ‘Surely you have some sort of emergency procedure arranged?’

‘No,’ said the courier. He spoke very quietly. ‘I’m afraid I haven’t. I just do the reports and pop them into the London dip mail secret tray. Sometimes it takes three days.’

‘Well this could be an emergency,’ I said. ‘Something should have been arranged beforehand.’ I rinsed off the last of the soap and parted my hair and straightened my tie.

‘I’ll follow you anyway,’ said the courier encouragingly. ‘It’s a fine morning for a walk.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.